Or: Power (Sometimes) to the People

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: not all inventions eliminate jobs. It only seems that way.

My friend Jeff (the actual Yard Ramp Guy) recently sent me a video filled with new construction machines: machines that can lay brick roads, and lay train tracks automatically, and place bridge segments from above, and plant rice faster than any human.

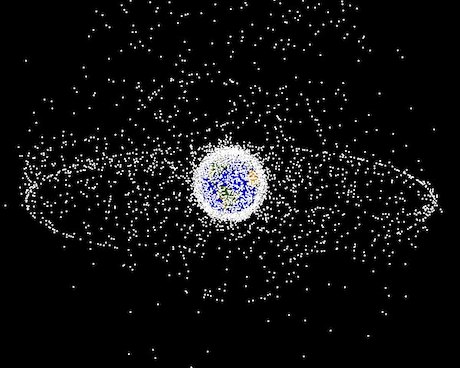

This is nothing new, of course. A great deal of history's inventions has resulted in lost jobs. Computers killed the typesetter. Robots have killed factory manufacturing jobs. Tractors, fertilizer, and other farming equipment are, by far, the biggest job killer.

In medieval Europe, more than 90% of workers were farmers. In 1820, 72% of Americans farmed. Today, less than two percent of Americans farm. Most of the displaced workers from these industries have ended up in service industry jobs in America.

Whole World in Tech's Hands?

A few factors usually counteract these job losses.

First, population growth. As populations increase, so does the economy and demand for goods and, therefore, jobs. In fact, one of the central premises of most economic plans is that population will keep increasing, thereby growing the economy.

Second, not all inventions eliminate jobs. Some actually create more jobs. This isn't always a good thing, of course. One of the most impactful job-creating inventions in all of history was the cotton gin. It created countless jobs by making cotton growing much more profitable and feasible. Unfortunately, slaves took on almost all of those jobs making American slavery that much more profitable and heinous.

That said, other job-creating inventions aren't nearly so bad. The Internet is a great example of this. Unfortunately, that's all about to change. Upcoming labor-saving technologies are reaching a point where they'll actually start costing net jobs.

More on that next time.

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: About the Warranty

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy explores and expands on the Warranty details.

Click HERE to read the fine print.

There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the

There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the

There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the

There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the