The decline of the castle can be summed up in one word: Gunpowder. Really seems a bit simple to just leave it there, so here goes:

The decline of the castle can be summed up in one word: Gunpowder. Really seems a bit simple to just leave it there, so here goes:

I generally avoid military history…always felt that people building things is more important to history than people destroying things. For any student of ancient architecture, though, castles are impossible to ignore.

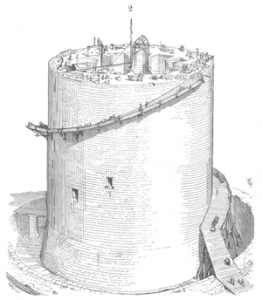

Castles dominated Europe for more than 900 years. When someone thinks of the Middle Ages, castles are probably the first things on their mind.

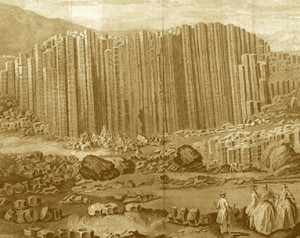

There were two major types of castles. Not architectural types; I’m talking about the reasons the castles were built in the locations they were. Rural castles were the first type, generally placed in a location with some sort of important resource—fertile land, mines, mills, or maybe a major road or mountain pass.

The second type, urban castles, were built to control the local populace and maintain control over trade routes. All of them served as centers for administration and as the habitations of the nobility.

Castles were not the only medieval fortifications. There were plenty of different kinds of forts and garrisons and such. The key difference between castles and the other fortifications is that castles were actually used for administration.

Only a century after gunpowder gained common use did artillery grew to be a major threat to castles. From that point, the decline of the castle was not so swift as you might expect. People built a few good castles after this time, a few of them even constructed to resist artillery—massively thick walls packed with dirt, rubble, and other debris.

The true death knell actually wasn’t artillery actually destroying the castles by artillery. It was a loss of confidence in the castles. The nobility simply started moving out, into grand palaces and estates.

The fall of castles as the center of European life was one of the main reasons that larger standing armies became a necessity, and led to one of the bloodiest eras in European history.

Of course, fancy nails alone aren’t enough to disaster-proof a house. You’ve got to design the whole building, foundation to roof, with that goal in mind. It’ll cost more and take more work, too, but this is a key part of designing a house to fit the environment it’s in. Which is one reason you see so many antique houses outlasting suburban cookie-cutter houses.

Of course, fancy nails alone aren’t enough to disaster-proof a house. You’ve got to design the whole building, foundation to roof, with that goal in mind. It’ll cost more and take more work, too, but this is a key part of designing a house to fit the environment it’s in. Which is one reason you see so many antique houses outlasting suburban cookie-cutter houses.