My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so: my From the Archives series. This week: the Tacoma Narrows offers us an important cautionary tale on preventing disaster and respecting nature.

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapse is one of the best known architectural failures in modern history, and it is used as a lesson by everyone, from architects and civil engineers to insurance agents.

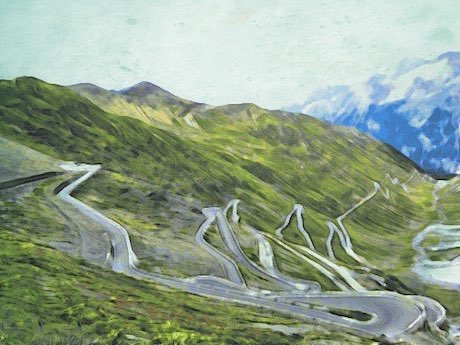

Built in 1940 across the Tacoma Narrows in Washington State, the suspension bridge lasted less than a year before collapsing. The only casualty was a dog stuck in a car.

Due to a very tight budget, the bridge was constructed with lightweight girders, as per the lowest bid design. (In my work, that Tacoma Narrows lesson is one of the many reasons I don't just go for the lowest bid). During construction, the bridge's thin design, low weight, and less-than-durable construction resulted in frequent vibrations and shaking whenever the wind picked up. It got so bad that the workers nicknamed it Galloping Gertie. Not exactly a trust-inspiring name.

The Bridge Collapses

The bridge began undergoing severe oscillations (or, to be a bit less technical about things: the bridge shook itself to bits) under heavy winds on November 7th, 1940.

I won’t go in depth on the science behind the collapse; you can find that easy enough. I'm more interested in what lessons it gives us about ignoring nature. For all the amazing things mankind has done, we still need to respect nature or it will come back to bite us. All of our technology and inventiveness allows us to stand up to nature, but push it around? Not a chance. We need to foster a design philosophy that promotes working with nature, not against it.

This sounds like hippy talk, I know, but it's nothing new. Heck, the idea goes back millennia. Look at any number of cultures that lived in hot climates—high ceilings, big windows, light colored paint. Cultures that live with heavy rain? You build your foundations strong, angle your roof, and pick your building site really carefully.

Why'd I decide to blog about Tacoma Narrows, when so many people already use it as a lesson? Well, I think some people missed that one ⏤ like my son-in-law, who decided to have his shed built by the cheapest contractor: at the edge of a hill, with no real foundation to speak of. He's going to be picking his tools out of the stream for weeks.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Smart Financing

When my friend The Yard Ramp Guy tells me I can save thousands of dollars, my ears perk up. And my bank account lofts skywards.

Click HERE to be uplifted.