My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: if it smelts fishy, it could be the remnants of the Stone Age. Or Bronze. Or Iron.

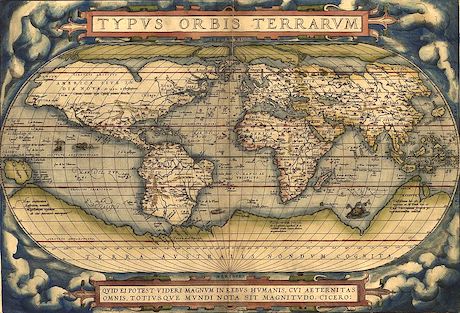

We’ve heard of the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. And yet, we aren't commonly taught why those ages occurred in that order. Which is just too bad, since it's pretty darn interesting.

We’ve heard of the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. And yet, we aren't commonly taught why those ages occurred in that order. Which is just too bad, since it's pretty darn interesting.

The Stone Age has a simple explanation. Stone is easier to work than metal, and more common. We figured out how to use it first.

Ancient humans actually did master use of some metal during this time period — namely meteoric iron, a natural alloy of nickel and iron present in iron meteorites. We sometimes heated it but more often shaped it, by cold hammering, into tools and arrowheads; the stuff was quite difficult to work.

The ancient Inuit inhabitants of Greenland, though, used iron much more extensively than other Stone Age people. Greenland has the world's only major deposit of telluric iron, also called native iron, which is iron that occurs in its pure metal state.

Looking for the right tool to advance our evolution

Native copper, however, is found worldwide (as are native gold, silver, and platinum, all of which are of limited use for tools.) The hardest and strongest common native metal on Earth, copper proved one of the most useful.

Eventually we learned to smelt metals from ore and, around 2500 BC, learned to alloy the two together to make bronze, kicking off The Bronze Age. Tin was somewhat rare outside the British Isles, parts of China, and South Africa, so it actually ended up commanding prices higher than gold in many regions. We frequently used zinc, more common than tin, to produce brass.

Iron smelting first occurred circa 1800 BC but didn't become common until 1200 BC. Eventually, of course, iron became the metal of choice for civilization—it's just much stronger than most of the other options.

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Bracing for the Elements

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy shows us how he's long been prepared for weather-related events.

Click HERE to discover a textbook-perfect example of being proactive.