Archive: Whales, Elephants & Dolphins

Animal Intelligence and Language, Part 3

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: Part 3 of my talking to the animals thingamabob.

Communication: Many Forms

Years ago, gibbons were thought to be one of the least intelligent apes. They repeatedly failed intelligence tests that other apes passed with ease, and they were quickly written off as stupid.

Then a group of researchers proposed something – seemingly obvious in retrospect – that was revolutionary at the time: Because gibbon hands weren't physically able to pick up objects from flat surfaces in the way other apes were capable, the researchers shouldn't be giving gibbons the same intelligence test as other apes.

When the researchers changed the test to better suit gibbon hand shape, the gibbon test scores skyrocketed, quickly landing alongside the other apes.

There's an important lesson to learn here. Summed up, we might say that judging others solely by our own standards might not be the best strategy ever.

You might be wondering why I’m starting a post about whales, elephants, and dolphins by talking about gibbons. It's for this exact lesson: our past attempts to crack the code of their conversations might have been foiled for similar reasons as the gibbon example.

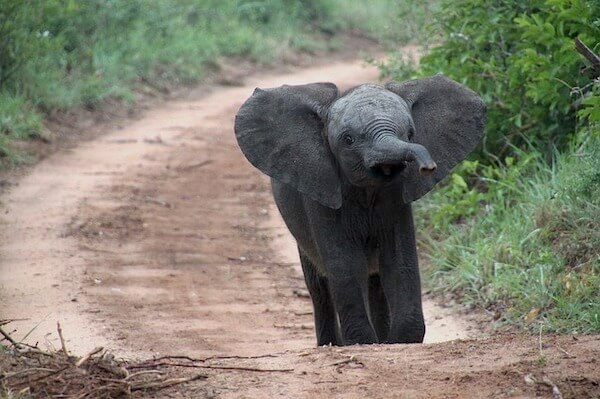

Let’s take a look at elephants first. They are tool users, have fantastic memories, are socially gregarious, are self-aware (can identify themselves in a mirror), and are generally agreed to be one of the most intelligent species in the animal kingdom. But what about language?

One of our biggest clues comes from a few interesting stories about elephants traveling long distances to hold wakes. Elephants are notorious for mourning their dead. We know that they’ve also done this for humans, even going so far as to give them burials. When celebrated elephant activist Lawrence Anthony died, two herds of wild elephants that Anthony had rehabilitated traveled from hours and hours away to hold a two-day wake outside of his house. How'd they know?

Well, it turns out that elephants are capable of generating incredibly loud noises that travel for miles and miles. Amazingly, those “loud” noises are too low for humans to hear. They can talk with other elephants at great distances and, apparently, are capable of conveying fairly complex information.

It goes deeper than that. Elephants appear to have massive numbers of learned behaviors—not just tool-using skills but also, apparently, cultural ones. Researchers have discovered surprisingly different social structures between herds, even among the same species. It would seem utterly astonishing if this was all accomplished without language of some sort.

Similar traits apply to dolphins and whales. Both are capable of making noises well above and below our hearing ranges. Both are also incredibly intelligent and social.

If we want to learn whether elephants, dolphins, whales, or other species truly have language—or, even more dauntingly, learn to understand or even speak it—we'll need to learn to start understanding how the lifestyles and physiologies of these animals would alter their needs and abilities in terms of communication.

We can't merely judge them by human standards.

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: The Inclined Plane in Verse

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy ends the year with a ridiculously fun riff on an old Christmas chestnut. The Mann can sell ramps, and he can rhyme. Bravo.

Sing along HERE.

Archives: Humans Speaking Animal

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: Part 2 of talking to the animals.

Last time around, we looked at animals speaking human language. What about humans trying to speak animal language?

Well, somewhat embarrassingly—and other than some scientifically and ethically suspect experiments with dolphins back in the day—we really hadn't tried too hard until fairly recently. We're looking into it with a vengeance now, and we're coming up with some astonishing results.

First of all, we've got parrots (like Alex) in the wild. We've confirmed they have words for specific types of predators, foods, etc. The most fascinating thing we've found, though, is that they give each other names. Each parrot has a distinct name that remains throughout its entire life, given to it by its mother. That's…pretty astonishing.

I just scampered in from Jackson Hole, and man are my dogs tired.

Next, we have prairie dogs. (Not groundhogs, I know; I couldn't resist the title.) Prairie dogs live in huge underground communities, and scientist Con Slobodchikoff has been studying their vocalizations fairly intensely over the years.

He's confirmed they have a variety of different danger calls. Essentially, they have words for hawk, human, coyote, and even domesticated dogs. This is quite useful, since each threat demands different responses.

Here's where it gets crazy, though: Slobodchikoff tried sending people, dressed differently, through the prairie dog villages and eventually realized that prairie dogs had the words that actually described individual humans. He found that the prairie dogs could differentiate the color of the humans' shirts, as well as differentiate between different shapes on their shirts.

The prairie dogs could identify the difference between triangles and circles, but not circles and squares. The ability to use adjectives like this is far from one expected in a species of rodents.

There are quite a few more obviously intelligent animals in the world than prairie dogs. They’ve got to have even more language, right? (So long as they’re social and not solitary, at least.)

_________

Next time: Animal Intelligence and Language, Part 3: Whales, Elephants, and Dolphins

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Selling Forklift Ramps on Craigslist

This week, the (real) Yard Ramp Guy takes us on a tour of Craigslist and its large equipment department. It ain't heavy. It's my yard ramp.

Read all about it HERE.

Archive: Animal Intelligence and Language

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: Part 1 of talking to the animals.

Alex, Talking About Things

Part 1: Birds of a Feather

Ever heard of Alex the grey parrot? Alex could supposedly use language, though his owner, animal psychologist Irene Pepperberg, quite cautiously claimed he could use a “two-way communications code.”

That, you know, involved Alex understanding more than a hundred words.

He could identify more than fifty different objects (and could even tell you what color it was or what material it was made of), could count to six, and even knew how to apologize and when it was appropriate.

Alex could invent names for things (he called apples “banerrys,” presumably a combination of banana and cherry, which he was more familiar with).

Every night, as Pepperberg left the lab Alex lived in, he'd tell her, “You be good, see you tomorrow. I love you.”

They were the last words he ever spoke to her. He died in his sleep at age 31.

So why, exactly, did Pepperberg refuse to say Alex used language?

Well, it's because of linguists. Or, more precisely: the animal intelligence debate, and the role linguists and animal cognitive scientists play. The debate is a complicated, in-depth, challenging thing, and trying to summarize doesn't do it justice. But I’ll give it a shot.

Essentially: Animal cognitive scientists believe that animals might be capable of using language, while linguists don't. (There are, of course, dissidents on both sides, but those are roughly the camps.)

Alex the grey parrot is hardly alone as evidence for animals being able to speak language. Gorillas and other great apes, for example, have been taught to speak sign language. Dogs and many other domesticated animals can learn extensive commands in human languages, though how much is them actually understanding and how much is them just learning behavioral triggers is a point of massive contention.

All that being said, Alex is the only known animal to have been able to ask questions, so that somewhat leans things back toward the linguist side of the argument, outside of Alex himself.

Here's the tricky bit, though: all of the above are animals trying to speak human languages, not humans trying to understand animal languages.

_________

Next time: Animal Intelligence and Language, Part 2: Groundhog Day

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Expert Insight

This week, the (real) Yard Ramp Guy honors the expertise of his manufacturers.

Read all about it HERE.

Archive: Egg Drop Reconsidered

Flooding you with Information

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: don't count your eggs before they've, uh, broken.

The egg drop competition has been a staple of elementary and middle school science classes since long before I was born. You create a container that will allow an egg to survive a drop of several stories, while still being able to put the egg in the container on-site. It’s a good exercise in creative thinking for kids, not to mention the fun factor.

An Egg

You’ve got a few basic strategies: the first—and simplest—is the “giant wad of padding” strategy, which usually works pretty well. The most common version of this is the big box filled with packing peanuts, but I’ve also seen bags made out of pillows and bubble wrap spheres. (Natch: I made all my kids and grandkids think more “outside the box” than this.)

The next most common is the parachute design—usually one of the more reliable ones, assuming your parachute works. Pretty self explanatory…and it’s the design I used myself as a kid. (A little extra padding didn’t hurt, of course.)

There are also a ton of weirder designs out there: flexible chopstick frameworks surrounding a bubble-wrap core, eggs padded in breakfast cereal or popcorn, containers filled with water (although that’s banned in many competitions), the panty hose box (suspend the egg in panty-hose in a box, and the stretchiness of the fabric will keep it from hitting the sides and breaking), and the small padded box covered in springs.

Then, of course, you have my cousin John’s approach. He always was too smart for his own good, so he decided to come up with something a bit more unusual. When he showed up for school that day, it was with a container shaped like a rocket; the thing even had landing struts. It was even weighted so that the container always fell bottom-first. What he didn’t tell anyone, of course, was that the rocket was weighted with an actual radio controlled model rocket engine and had a thin paper coating over it.

When the teacher dropped his off the roof (all us kids standing below), John, who’d been hiding his remote in his pants, pulls it out to activate it. Unfortunately, it didn’t go quite as anticipated and shot off sideways toward the kids. Guess who it hit?

And that’s the story about how I got a broken rib, minor burns, and a face covered in egg. It wouldn’t be the first or the last time that hanging out with my cousin got me injured, either. At least that time I didn’t get in trouble for it.

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Streamlined Steel

This week, the (real) Yard Ramp Guy highlights a very promising, cleaner future for the air we breathe.

Read all about it HERE.