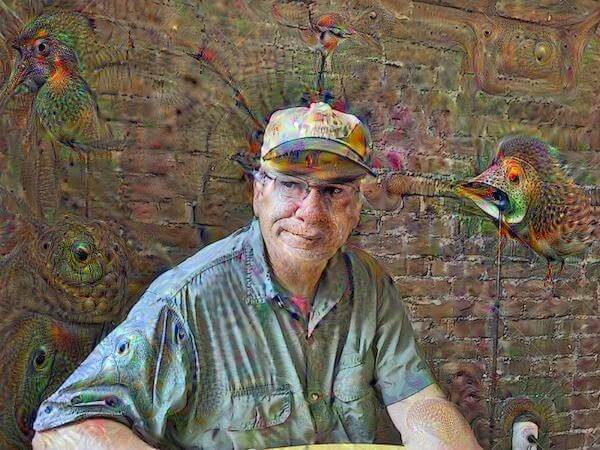

Part 1: Birds of a Feather

Alex, Talking About Things

Ever heard of Alex the grey parrot? Alex could supposedly use language, though his owner, animal psychologist Irene Pepperberg, quite cautiously claimed he could use a “two-way communications code.”

That, you know, involved Alex understanding more than a hundred words.

He could identify more than fifty different objects (and could even tell you what color it was or what material it was made of), could count to six, and even knew how to apologize and when it was appropriate.

Alex could invent names for things (he called apples “banerrys,” presumably a combination of banana and cherry, which he was more familiar with).

Every night, as Pepperberg left the lab Alex lived in, he'd tell her, “You be good, see you tomorrow. I love you.”

They were the last words he ever spoke to her. He died in his sleep at age 31.

So why, exactly, did Pepperberg refuse to say Alex used language?

Well, it's because of linguists. Or, more precisely: the animal intelligence debate, and the role linguists and animal cognitive scientists play. The debate is a complicated, in-depth, challenging thing, and trying to summarize doesn't do it justice. But I’ll give it a shot.

Essentially: Animal cognitive scientists believe that animals might be capable of using language, while linguists don't. (There are, of course, dissidents on both sides, but those are roughly the camps.)

Alex the grey parrot is hardly alone as evidence for animals being able to speak language. Gorillas and other great apes, for example, have been taught to speak sign language. Dogs and many other domesticated animals can learn extensive commands in human languages, though how much is them actually understanding and how much is them just learning behavioral triggers is a point of massive contention.

All that being said, Alex is the only known animal to have been able to ask questions, so that somewhat leans things back toward the linguist side of the argument, outside of Alex himself.

Here's the tricky bit, though: all of the above are animals trying to speak human languages, not humans trying to understand animal languages.

_________

Next time: Animal Intelligence and Language, Part 2: Groundhog Day

The Yard Ramp Guy®: Back to Yard Ramp Basics

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy waxes in a fine way about the beautiful simplicity of the yard ramp. Honored that he quotes me in the piece.

Check out his new blog HERE.