Or: Undraining the Moat

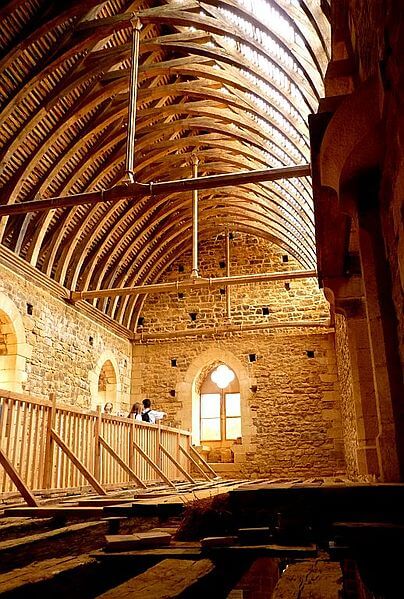

There's a castle under construction in France. Not a Disney-style castle at a theme park. An actual castle using medieval designs, materials, and construction methods.

There's a castle under construction in France. Not a Disney-style castle at a theme park. An actual castle using medieval designs, materials, and construction methods.

Guédelon Castle started construction in 1997 and won't be completed until sometime in the 2020s. The designers aim to create an authentic 13th century-style medieval castle.

Oh, and when they say authentic, they mean authentic:

- They only use local materials.

- The site for the castle was chosen very carefully, located near an old stone quarry, a pond, and right in the middle of a forest.

- All of the materials are gathered and hauled to the site using only medieval methods, including horse drawn carts.

- The construction workers all wear period-appropriate garb, use period-appropriate tools, and use period-appropriate construction methods.

- They have on-site blacksmiths, stone masons, carpenters, etc.

- No modern tools are used anywhere. Not even ramps; sorry, Yard Ramp Guy.

The project has created 55 jobs and attracted more than 200 volunteers. On-site professional training is provided to disadvantaged youth, some of whom have earned stone-masonry and other certifications. More than 300,000 tourists a year visit the project, and it is open to schools for educational purposes. The construction has definitely proven itself worthwhile in those regards, but none of those were the original intention.

This is all part of experimental archaeology, which reconstructs and uses ancient tools, structures, and artifacts and allows archaeologists to actually study which methods work best and produce results most like the actual artifacts.

One way they do that is by looking for construction quirks (not the actual scientific term they use). Anyone who uses a lot of tools knows that you'll end up with certain quirks in your project, depending on which tools you use. For example: the same cut will be slightly different with different saws. When you're using tools that aren't mass-produced like ours, those little quirks get magnified even more.

During experimental archaeology, you can look to see if the methods you are using produce quirks like the historical ones.

Experimental archaeologists have produced Iron Age farmsteads and Greek triremes, hauled Stonehenge sized stones, sailed from Peru to Polynesia on a raft (Kon-Tiki), and, of course, built Guédelon Castle. (For a longer list, check out THIS. It's an incredibly productive line of research. And a heck of a lot of fun.

Guédelon Castle is proving to be one of the most productive of these lines of research. We've learned tremendously about castle construction from it. There was actually a companion castle being built in America: the Ozark Medieval Fortress. It ran out of funding and is currently on hiatus. We still need that European vacation to see a castle under construction. With any luck, though, that will change.

_____

Photo By Ronny Siegel (Château Guedelon) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

One of his best known pieces is a work called

One of his best known pieces is a work called

Photo by Arshiya Urveeja Bose [

Photo by Arshiya Urveeja Bose [ The most famous of the bridges, the Umshiang Double-Decker Root Bridge, is actually two of those bridges, with one stacked directly over the other. Local dedication to the art has kept the bridges alive and prevented them from being replaced with steel. (Steel, frankly—and with all respect to those dealing with, ahem,

The most famous of the bridges, the Umshiang Double-Decker Root Bridge, is actually two of those bridges, with one stacked directly over the other. Local dedication to the art has kept the bridges alive and prevented them from being replaced with steel. (Steel, frankly—and with all respect to those dealing with, ahem,