Or: Did That Building Just Run a Red Light?

Stay with me on this one: yes, it begins on a pretty sour note…but I promise you there’s a happy ending.

Nineteenth century Chicago was plagued by, well, plagues. Epidemics of typhoid fever, dysentery, and cholera repeatedly hit the city. The 1854 cholera outbreak killed six percent of the entire city's population.

Nineteenth century Chicago was plagued by, well, plagues. Epidemics of typhoid fever, dysentery, and cholera repeatedly hit the city. The 1854 cholera outbreak killed six percent of the entire city's population.

The reason for those diseases, and a common culprit throughout history: poor-to-nonexistent drainage. Standing water in a city makes a perfect breeding area for all sorts of nasty illness. In fact, disease historically was so bad that the majority of medieval cities experienced negative population growth—more people died of diseases than were born.

The only reason cities didn't depopulate was a near constant influx of immigration from the country. This changed steadily around the world when city infrastructure and medicine improved. Disease was still quite common in the 19th century, but Chicago's level of disease was quite unusual in an American city for the time.

In 1856, an engineer named Ellis S. Chesbrough developed a plan for a city-wide sewer system that would solve the problem. It was unusually ambitious: he wanted to raise the entire city six feet, then build sewers below the newly raised buildings.

In 1856, an engineer named Ellis S. Chesbrough developed a plan for a city-wide sewer system that would solve the problem. It was unusually ambitious: he wanted to raise the entire city six feet, then build sewers below the newly raised buildings.

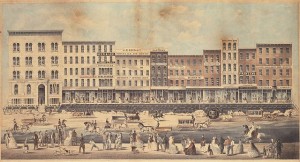

Sounds insane, right? That's what I thought, too, except they actually did it—raising the first building in January 1858: a four-story, 70 foot long, 750-ton brick structure lifted on two hundred jackscrews to its new level, without the slightest damage. Engineers boosted more than 50 masonry buildings that year alone.

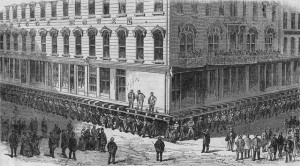

In 1860, a team of engineers actually managed to raise up half a city block in one go—an estimated 35,000 tons lifted nearly five feet into the air by 600 men using 6,000 jackscrews. They were so confident in the process that businesses didn't even close during the the five days it took to lift the whole thing.

On the last day of the process, before they began work on the new foundations, they allowed crowds to walk underneath the buildings, among the jacks. At another point, a six-story hotel was raised up without the guests even realizing it.

Only masonry buildings were considered worth raising; they placed wood-framed buildings on large rollers and moved them to the outskirts of town, usually without even bothering to empty out the furniture first.

Only masonry buildings were considered worth raising; they placed wood-framed buildings on large rollers and moved them to the outskirts of town, usually without even bothering to empty out the furniture first.

This was so common that, for quite a few years, people considered looking out the window to see a building going past just another day of normal traffic.

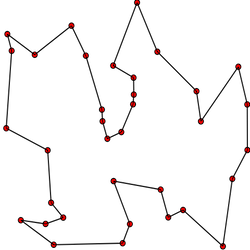

Let's say there's a traveling salesman trying to hit a certain group of towns during a week. (I know, I know: eCommerce is eclipsing the traveling salesman these days, but I’m Old School, so bear with me.) To save time, this traveling salesman wants to calculate the best possible route between all the cities—the route with the absolute shortest possible distance—before he returns to the starting city.

Let's say there's a traveling salesman trying to hit a certain group of towns during a week. (I know, I know: eCommerce is eclipsing the traveling salesman these days, but I’m Old School, so bear with me.) To save time, this traveling salesman wants to calculate the best possible route between all the cities—the route with the absolute shortest possible distance—before he returns to the starting city.

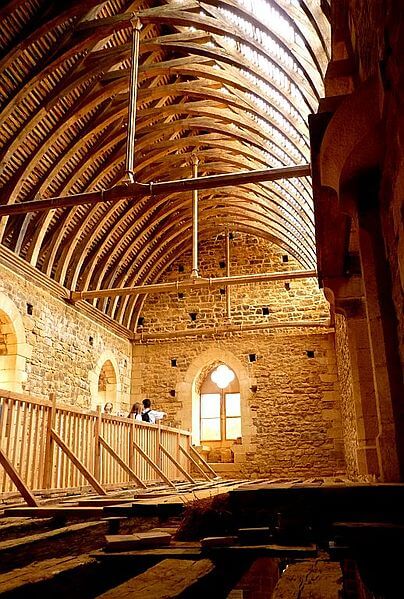

There's a castle under construction in France. Not a Disney-style castle at a theme park. An actual castle using medieval designs, materials, and construction methods.

There's a castle under construction in France. Not a Disney-style castle at a theme park. An actual castle using medieval designs, materials, and construction methods. There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the

There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the  The architects and construction crew faced a number of major difficulties in the construction. Earthquake proofing was one of the biggest hurdles. Another: preventing buckling and sagging in the ground overhead as they dug out the complex; it is directly underneath a city, after all.

The architects and construction crew faced a number of major difficulties in the construction. Earthquake proofing was one of the biggest hurdles. Another: preventing buckling and sagging in the ground overhead as they dug out the complex; it is directly underneath a city, after all.