When it comes to getting into space, rockets are pretty much staircases at best. More like ladders, really.

Space Elevator

That’s a bizarre thing to say, I know, but hear me out. Rockets are expensive and dangerous, but they’re still the best way we have of getting to space. (There are a couple of other ways, like Orion drives, but given that those things basically ride nuclear explosions…) There’s a theoretical method, that works much, much better: the space elevator. (Hence the staircase joke. Well, I thought it was funny, at least. So I’m not a professional comedian, so sue me.)

A space elevator is, essentially, a long cable—anchored at the equator, extending out into orbit. It works sort of like when you spin while holding a rope, and the rope is suspended above the ground by centrifugal force. (Or is it centripetal? I can never remember.) It’s not quite the same, of course, since it has to have a counterweight at the end, along with several other requirements.

Once the cable is up, cargo and passenger pods would be able to freely move up and down it, at much, much lower costs than rockets. Did I mention how expensive rockets are? Really, really expensive. As in: $10,000 to $25,000 per kilogram they need to lift. (For those of you who don’t have your measurement conversion tables memorized, one kilogram is equal to a bit more than two pounds.)

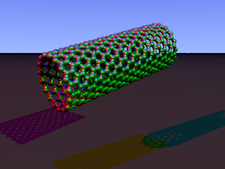

Carbon Tube

So why aren’t we using them now? Well, because we don’t have a strong enough cable. People keep bringing up carbon nanotubes as an option, but since we don’t have those yet, we just can’t build it.

The space elevator would be more than possible on other, smaller objects in the Solar System. We could build a space elevator on the moon with ordinary Kevlar.

Space elevators aren’t the only ideas for getting to space without rockets. Other ideas are floating out there, ranging from rocket sleds (which does actually involve rockets, but in a much more affordable manner) to skyhooks, which resemble something that a mad scientist, a six year old, and an engineer would design together if asked to create the nuttiest amusement park ride ever, all while hooked to caffeine IV drips.

Of course, fancy nails alone aren’t enough to disaster-proof a house. You’ve got to design the whole building, foundation to roof, with that goal in mind. It’ll cost more and take more work, too, but this is a key part of designing a house to fit the environment it’s in. Which is one reason you see so many antique houses outlasting suburban cookie-cutter houses.

Of course, fancy nails alone aren’t enough to disaster-proof a house. You’ve got to design the whole building, foundation to roof, with that goal in mind. It’ll cost more and take more work, too, but this is a key part of designing a house to fit the environment it’s in. Which is one reason you see so many antique houses outlasting suburban cookie-cutter houses.