I've been composing this blog since July of 2014. That's five years and 151 entries. My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so: my From the Archives series. Fitting, then to start from the very beginning, with my very first entry...

The pyramids are among the wonders of the ancient world for a pretty simple reason: they're huge. Doesn't take much to figure that one out. But what got me interested in the pyramids in the first place was their construction.

The ancient Egyptians obviously didn't have the technology for moving heavy loads that we did. All they had were a few primitive cranes, some basic levers and rollers, and, of course, ramps.

The ancient Egyptians obviously didn't have the technology for moving heavy loads that we did. All they had were a few primitive cranes, some basic levers and rollers, and, of course, ramps.

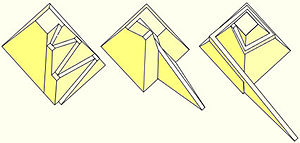

The old idea about how the Egyptians built the pyramids involved thousands of slaves hauling blocks up huge straight ramps to the top. It looks cool in the movies, but it doesn't actually work that well. The amount of material and labor needed to construct straight ramps to the top—and to continue building them up as the pyramid grows—is pretty close to the amount you'd need to build the actual pyramid itself, not to mention that they haven't actually found any evidence for ramps that colossally huge. Building ramps that huge, I say, is just a waste.

It seems more likely that they instead either zigzagged the ramp up one side or spiraled it around the pyramid, using uncompleted segments as the ramp. This would have allowed them to construct the vast majority of the pyramid easily, though the top third of the structure would have needed to be moved up, using levers. Since it's so much narrower at the top, though, that top third makes up less than five percent of the total weight of the pyramid. That's working smart.

It seems more likely that they instead either zigzagged the ramp up one side or spiraled it around the pyramid, using uncompleted segments as the ramp. This would have allowed them to construct the vast majority of the pyramid easily, though the top third of the structure would have needed to be moved up, using levers. Since it's so much narrower at the top, though, that top third makes up less than five percent of the total weight of the pyramid. That's working smart.

Historians and archaeologists also think that rather than huge hordes of slaves, the pyramids were constructed by smaller teams of well-paid skilled laborers, who were cheaper than feeding an army of slaves and got things done much quicker. No one's said anything about ancient Egyptian unions, but I've got some cheerful suspicions about that.

The Yard Ramp Guy®: Planned Industrial Longevity

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy makes a Ramp Rules-worthy connection between Greta Garbo's perfume and industrial yard ramps.

Sniff it out it HERE.