My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so: my From the Archives series. This week: Terraces⏤the opposite of ramps?

The Inca are surely one of my favorite ancient cultures. Much of this is due to the unusual amount of research available on their building techniques and architecture. The pieces of their engineering I've been reading about lately are their terraces.

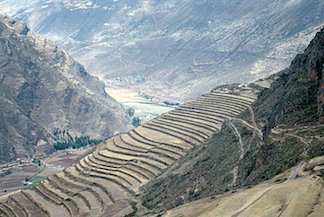

Terraces might be something of an opposite of ramps, but that just makes them more fascinating. Living among some of the steepest mountains in the world, the Incans had to improvise heavily when it came to all sorts of facets of their life. Their terraces did a lot more than provide flat areas for food production (though don't get me wrong: that was just a little bit important); they also helped to control erosion and landslides.

In fact, much of Incan architecture was built to be earthquake resistant, and the terraces were no exception. They were so well built that, despite the Incan's comparatively low technological level, their terraces survived from Pizarro's conquest of their empire, totally forgotten, all the way up to the twentieth century, when they were rediscovered.

Do you think anything we build today would last that long without maintenance? Not likely. This workmanship stretched all the way through their construction, too.

The Incans by no means had a monopoly on agricultural terraces, of course. Terrace farming has arisen independently in dozens of cultures worldwide, with almost as many individual styles. It's almost certainly the most efficient method of farming in the mountains.

The most famous are almost certainly the rice terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras: they've actually been declared a UNESCO heritage site. You've almost certainly seen images of them before. They've been farmed continuously for something like 2000 years, which is absolutely crazy. That's not just architecture, it's a way of life.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: The Power of Powder

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy writes his own cautionary tale of sorts: some seemingly sci-fi tale of producing a yard ramp with a 3-D printer.

Click HERE to read all about it.

The Diolkos, built by the ancient Greeks, was half ramp, half causeway. It was used to transport ships across the Ithmus of Corinth, saving them a dangerous sea voyage. The ancient Greeks actually dragged the ships overland on it. (You'd think a canal would be easier to use, but canals are a lot harder to build and maintain.) Huge teams of men and oxen would have pulled the boats and cargo across it in about three hours per trip.

The Diolkos, built by the ancient Greeks, was half ramp, half causeway. It was used to transport ships across the Ithmus of Corinth, saving them a dangerous sea voyage. The ancient Greeks actually dragged the ships overland on it. (You'd think a canal would be easier to use, but canals are a lot harder to build and maintain.) Huge teams of men and oxen would have pulled the boats and cargo across it in about three hours per trip.

The ancient Egyptians obviously didn't have the technology for moving heavy loads that we did. All they had were a few primitive cranes, some basic levers and rollers, and, of course, ramps.

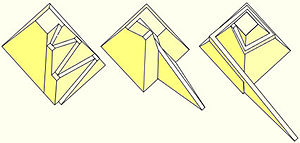

The ancient Egyptians obviously didn't have the technology for moving heavy loads that we did. All they had were a few primitive cranes, some basic levers and rollers, and, of course, ramps. It seems more likely that they instead either zigzagged the ramp up one side or spiraled it around the pyramid, using uncompleted segments as the ramp. This would have allowed them to construct the vast majority of the pyramid easily, though the top third of the structure would have needed to be moved up, using levers. Since it's so much narrower at the top, though, that top third makes up less than five percent of the total weight of the pyramid. That's working smart.

It seems more likely that they instead either zigzagged the ramp up one side or spiraled it around the pyramid, using uncompleted segments as the ramp. This would have allowed them to construct the vast majority of the pyramid easily, though the top third of the structure would have needed to be moved up, using levers. Since it's so much narrower at the top, though, that top third makes up less than five percent of the total weight of the pyramid. That's working smart.