Or: Tuff Luck

The Turkish Underground

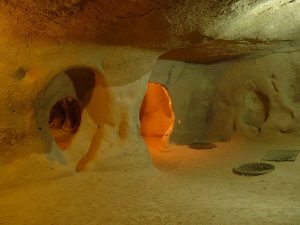

The Cappadocia region of Anatolia, Turkey, is riddled with underground cities. In 1963, a man in the region knocked down a wall of his home (for home renovations, I hope, though maybe he was just in a particularly bad mood) and discovered a mysterious room built into the rock.

After a little more digging, he broke into a whole intricate tunnel system: the Derinkuyu underground city, carved thousands of years ago.

The Cappadocia region sits on a one kilometer (3,300-foot) tall volcanic plateau. Millions of years ago, it was covered in volcanic ash, which solidified into tuff, a type of volcanic rock.

That made for easy digging, and the inhabitants of the region some 3,000 years ago quickly took advantage of this to dig their elaborate tunnel cities. (Not all tuffs are soft and easily dug into, however; some tuffs are extremely tough.)

People developed a wide range of uses within the tunnel systems. Food storage was one of the earliest and most reliable: cave systems tend to maintain constant temperatures, often considerably cooler than the surface.

We’ve also used underground cities multiple times throughout history to hide from attack. Derinkuyu is extensive enough that it could have hidden as many as 20,000 people. They had the benefit of ample storage space, which included wine and oil presses, stables, refectories, and chapels.

The city contains five different levels, each of which could be closed off independently of the others. Not least incredibly, the Derinkuyu is also connected to the Kaymakli underground city by an 8 km (5 mile) underground tunnel.

There is some debate about who first built the cities. Some attribute them to the Hittites (between the 15th and 12th centuries BC), but most believe they were constructed by the Phrygians (between the 8th and 7th century BC), the people who supplanted the Hittites, and then themselves faded away during Roman times.

The Derinkuyu was used by the Byzantines much later to defend themselves during the Arab Byzantine wars (780-1180 AD). Even as late as the early 20th century, the tunnels were still in use by the locals to avoid Ottoman persecution, only falling into disuse in 1923. So, doing our math, the lost city had only been lost for 40 years when it was re-found.

Today, much of the Derinkuyu underground city is open for visitation by tourists. And more than 200 other underground cities with a minimum of two levels (40 have three or more) have been discovered in the region.