On Roman Concrete

Learning from the School of Hard Rocks

It's Written in the Concrete

Though the Romans have a pretty impressive reputation, in many regards they weren't nearly so clever as people tend to think they were.

For example, their fabled legions, while effective early in Roman history, became rather useless toward the end: the knight was basically invented by barbarians looking to defeat Roman legions. Even after it became apparent that the legions were a tool of the past, the Romans foolishly just kept sticking with it.

However, one area in which they were unquestionably brilliant was in architecture and construction.

Much has been made of Roman aqueducts and other construction techniques, but one technology that doesn't get discussed nearly as much as it should is their concrete. Roman concrete—known as opus caementicium—is, interestingly, much more durable than modern day concrete.

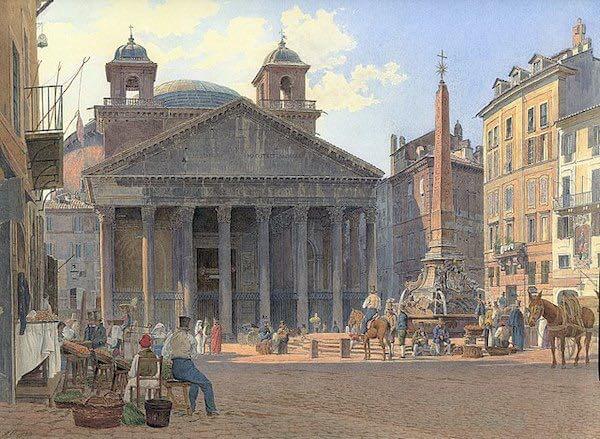

We have many examples of Roman concrete that have survived all the way to today. The Pantheon in Rome (not to be confused with the Parthenon), for instance, is a concrete dome that has survived intact since 126 AD.

Even more impressive is Roman concrete's resistance to seawater. Seawater is incredibly corrosive to modern buildings, corroding and destroying them in mere decades. We're lucky to get 50 years out of modern concrete. Roman concrete, however, can survive immersion in seawater for centuries or even millennia; plenty of docks and pilings from Roman times can still be found off European shorelines.

What was their secret? Well, we don't know the exact composition of Roman concrete, but we do know one of the major secrets: they used volcanic ash instead of the fly ash we use today. When submerged in seawater, the seawater reacts with the mineral phillipsite, found in volcanic ash. Over time, a new mineral known as tobermorite forms in the cracks of the concrete. As it forms, the concrete actually gets stronger and stronger.

Roman concrete today is stronger than when it was first laid down.

Many people are trying to mimic Roman concrete today. Not only is it more durable and long lasting, but it's also cheaper and more environmentally friendly. The problem, of course, is the extremely long setting time: most builders don't want to wait long enough for Roman concrete to set.

Haste makes waste. Some people are okay with that. Roman concrete endures.

The Yard Ramp Guy®: Going Above & Beyond

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy describes how his team focuses on building trust and relationships. It's healthy and refreshing to read of such a fine approach.

Check out his new blog HERE.

The Bone Wars

Marsh and Cope Have a Falling Out

Beware of Humans

There's one field of geology notably unrepresented at the United States Geological Survey: paleontology. This seems like a fairly major omission, and it's all thanks to a series of events known as the Bone Wars.

During the Gilded Age (the last thirty years or so of the 1800s in America), paleontology was an incredibly competitive field. At the time, we collected dinosaur fossils more rapidly than ever before. Two figures stood out above all the rest—Edward Drinker Cope, of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, and Othniel Charles Marsh.

Marsh and Cope began as friends when they first met in Berlin (Germany has always been a paleontological treasure trove), but their relationship began to sour quickly. By the early 1870s, things heated up to an absurd degree. A series of mishaps, oddities, and minor snubs, along with the fundamentally incompatible personalities of the two men, irrevocably ruined things between them.

In 1873, the Bone Wars began in earnest. The first shots fired were academic ones: renaming and reclassifying species to mess with the other, publicly pointing out one another's errors, and the like.

If things had stayed like that, it wouldn't have made history the way it did; academic rivalries are, as they say, a dime a dozen. However, the confrontation escalated rapidly from there.

Marsh and Cope began hiring employees away from one another, bribing officials to advantage themselves and hurt the other, stealing fossils from one another's sites, and so on and so forth. They actively tried to destroy one another's reputations, and even turned to destroying fossils rather than letting the other get his hands on them. Financially and professionally, the rivalry eventually ruined both of them, and they never abandoned it.

The two scientists discovered 136 new species during the Bone Wars, including Triceratops and Stegosaurus. (Before then, we had only nine named species of dinosaur in North America.)

Unfortunately, the Bone Wars also did much to damage the reputation of American paleontology. It resulted in the loss of numerous fossils, the USGS losing its paleontology division, and a severe, decades-long blow to the reputation of American paleontology.

The Yard Ramp Guy®: Location, Location, Location

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy tells us all about placement and location, location, location. And he uses a novel way of website strategy to reflect on the right yard ramps themselves.

Check out his new blog HERE.

Whales, Elephants, and Dolphins

Animal Intelligence and Language, Part 3

Communication: Many Forms

Years ago, gibbons were thought to be one of the least intelligent apes. They repeatedly failed intelligence tests that other apes passed with ease, and they were quickly written off as stupid.

Then a group of researchers proposed something – seemingly obvious in retrospect – that was revolutionary at the time: Because gibbon hands weren't physically able to pick up objects from flat surfaces in the way other apes were capable, the researchers shouldn't be giving gibbons the same intelligence test as other apes.

When the researchers changed the test to better suit gibbon hand shape, the gibbon test scores skyrocketed, quickly landing alongside the other apes.

There's an important lesson to learn here. Summed up, we might say that judging others solely by our own standards might not be the best strategy ever.

You might be wondering why I’m starting a post about whales, elephants, and dolphins by talking about gibbons. It's for this exact lesson: our past attempts to crack the code of their conversations might have been foiled for similar reasons as the gibbon example.

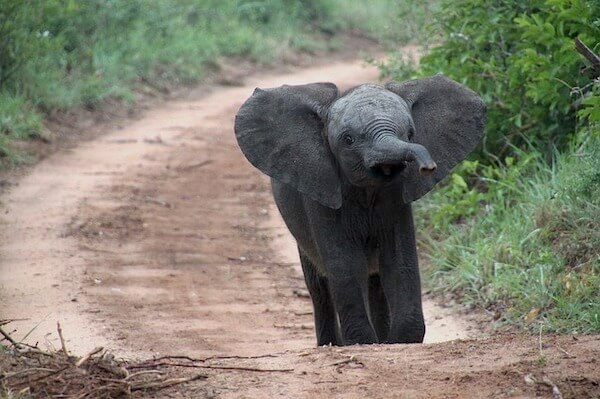

Let’s take a look at elephants first. They are tool users, have fantastic memories, are socially gregarious, are self-aware (can identify themselves in a mirror), and are generally agreed to be one of the most intelligent species in the animal kingdom. But what about language?

One of our biggest clues comes from a few interesting stories about elephants traveling long distances to hold wakes. Elephants are notorious for mourning their dead. We know that they’ve also done this for humans, even going so far as to give them burials. When celebrated elephant activist Lawrence Anthony died, two herds of wild elephants that Anthony had rehabilitated traveled from hours and hours away to hold a two-day wake outside of his house. How'd they know?

Well, it turns out that elephants are capable of generating incredibly loud noises that travel for miles and miles. Amazingly, those “loud” noises are too low for humans to hear. They can talk with other elephants at great distances and, apparently, are capable of conveying fairly complex information.

It goes deeper than that. Elephants appear to have massive numbers of learned behaviors—not just tool-using skills but also, apparently, cultural ones. Researchers have discovered surprisingly different social structures between herds, even among the same species. It would seem utterly astonishing if this was all accomplished without language of some sort.

Similar traits apply to dolphins and whales. Both are capable of making noises well above and below our hearing ranges. Both are also incredibly intelligent and social.

If we want to learn whether elephants, dolphins, whales, or other species truly have language—or, even more dauntingly, learn to understand or even speak it—we'll need to learn to start understanding how the lifestyles and physiologies of these animals would alter their needs and abilities in terms of communication.

We can't merely judge them by human standards.

The Yard Ramp Guy®: The Inclined Plane in Verse

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy ends the year with a ridiculously fun riff on an old Christmas chestnut. The Mann can sell ramps, and he can rhyme. Bravo.

Sing along HERE.

Humans Speaking Animal

Animal Intelligence and Language, Part 2: Groundhog Day

I just scampered in from Jackson Hole, and man are my dogs tired.

Last time around, we looked at animals speaking human language. What about humans trying to speak animal language?

Well, somewhat embarrassingly—and other than some scientifically and ethically suspect experiments with dolphins back in the day—we really hadn't tried too hard until fairly recently. We're looking into it with a vengeance now, and we're coming up with some astonishing results.

First of all, we've got parrots (like Alex) in the wild. We've confirmed they have words for specific types of predators, foods, etc. The most fascinating thing we've found, though, is that they give each other names. Each parrot has a distinct name that remains throughout its entire life, given to it by its mother. That's…pretty astonishing.

Next, we have prairie dogs. (Not groundhogs, I know; I couldn't resist the title.) Prairie dogs live in huge underground communities, and scientist Con Slobodchikoff has been studying their vocalizations fairly intensely over the years.

He's confirmed they have a variety of different danger calls. Essentially, they have words for hawk, human, coyote, and even domesticated dogs. This is quite useful, since each threat demands different responses.

Here's where it gets crazy, though: Slobodchikoff tried sending people, dressed differently, through the prairie dog villages and eventually realized that prairie dogs had the words that actually described individual humans. He found that the prairie dogs could differentiate the color of the humans' shirts, as well as differentiate between different shapes on their shirts.

The prairie dogs could identify the difference between triangles and circles, but not circles and squares. The ability to use adjectives like this is far from one expected in a species of rodents.

There are quite a few more obviously intelligent animals in the world than prairie dogs. They’ve got to have even more language, right? (So long as they’re social and not solitary, at least.)

_________

Next time: Animal Intelligence and Language, Part 3: Whales, Elephants, and Dolphins

The Yard Ramp Guy®: Appreciating the Yard Ramp

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy continues to honor the beauty of a yard ramp with a terrific perspective on its logistical and economic value.

Check out his new blog HERE.