Or: My Orange Roughy Lament

Rough Times for Roughy

I go freshwater fishing all the time, but I'm a big seafood fan and still buy a lot of saltwater fish from the store.

(One of my favorite shows is River Monsters. Back in the day, I loved watching Harold Ensley’s “The Sportsman’s Friend, a bit for his calm, cool approach to all things hunting and fishing, though mostly for the awe of seeing him catch awesomely-sized fish…and then unhook and drop them back in the water. Harold may never have been hungry.)

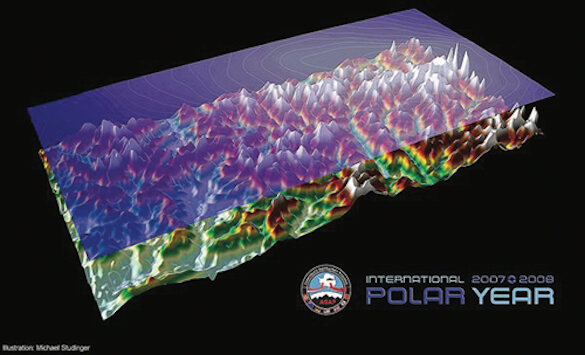

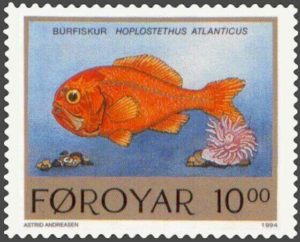

A few years ago, there was this fish I adored, Orange Roughy, that, well, simply stopped showing up in stores. Turns out that this deep-dwelling creature is extremely vulnerable to overfishing. The Orange Roughy can live to an astonishing 149 years yet often don't start reproducing until age 40 and, when they do, lay a relatively small amounts of eggs (for fish).

We had almost wiped out the Orange Roughy before we started realizing how endangered their stocks were getting. These days, thanks to careful conservation, their fisheries have recovered enough that limited fishing has resumed. But it was a close call there for a while.

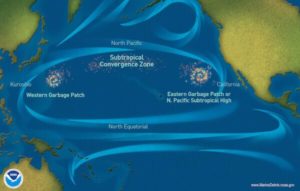

The scary thing is that this is not an isolated event. We have MASSIVELY overfished our oceans. It's estimated that we put in 17 times as much work for each fish we catch today as fishermen did a century ago.

Even with all of the advanced tech we use today, fishing remains much harder and less rewarding.

That's nowhere near the scariest statistic, though: More than 90% of all large bony fish are gone from our oceans.

Some fisheries, however, are quite sustainable and make excellent seafood choices. These include:

- The Florida Stone Crab. There is little to no bycatch (unwanted animals caught along with the catch, most of which die and are discarded; tiger prawns are the worst offenders for bycatch). Plus, most of the crabs caught actually survive. We just harvest a single claw and let them go.

- Arctic Char. The product of well-managed fisheries, along with some of the few sustainable aquaculture programs that don’t cause massive problems in the regions around them.

- Pacific Cod. While Atlantic Cod fisheries are a mess, Pacific Cod fisheries are in pretty good shape. Avoid Russian and Japanese Cod, though. They're often overfished.

For a fairly thorough listing of environmentally responsible fisheries, Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch has an interactive website.

_________

Quotable

Oh, Mr. Yard Ramp Guy—Heck, Mann:

“Half the world is composed of people who have something to say and can't, and the other half who have nothing to say and keep on saying it.”