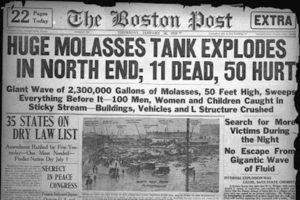

Faster Than Molasses in January

Spilt

On January 15, 1919, a storage tank in Boston broke, releasing 2.3 million gallons of molasses. The resulting wave of molasses rolled through the streets at about 35 miles per hour. In all, 21 people died and 150 were injured.

The actual failure can be traced to stress failures in the huge cylindrical tank. The steel was only about half as thick as it should have been and completely lacked manganese, which would have made it less brittle.

The company that owned it skipped basic safety tests, like filling the tank with water before use to check for leaks.

Compounding all of this was a rapid increase in temperature over the course of the day (almost 40 degrees), which contributed toward weakening the storage tank, resulting in the massive failure.

Rescue efforts were badly hampered by the fact that the molasses didn't clear away quickly. It remained clumped up in knee-high pools, and the search for victims took more than four days.

Workers finally used a fireboat to pump salt water from the harbor over the molasses, eventually clearing it away. Cleanup workers tracked molasses all over. Much of the city was perpetually sticky for weeks and months afterward, and the molasses stained the harbor brown until the summer.

More than a century before, on October 17, 1814, a vat containing more than 162,000 gallons of porter ruptured in London, causing multiple other vats in the same building to collapse as well. All told, almost 388,000 gallons of beer were released into the streets.

Only eight people died, due to the much smaller quantity of fluid than the Boston molasses disaster, less-crowded streets, and the lower viscosity of beer compared to molasses.

The torrent of beer demolished two houses, severely damaged a nearby pub, and flooded a nearby wake.

Otherwise, quite a few people sustained injuries when they ran outside to collect beer, making sure it didn't go to waste.

_________

Quotable

Oh, Yard Ramp Guy: my blog-relevant quotations continue…

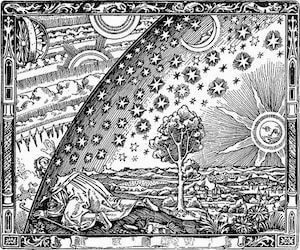

If you answered Copernicus or Galileo, you're off by a millennia or two. The Ancient Greeks actually discovered this.

If you answered Copernicus or Galileo, you're off by a millennia or two. The Ancient Greeks actually discovered this. In fact, we can trace the popularization of the idea that people thought the Earth was flat back to specific historians in the 1800s.

In fact, we can trace the popularization of the idea that people thought the Earth was flat back to specific historians in the 1800s.

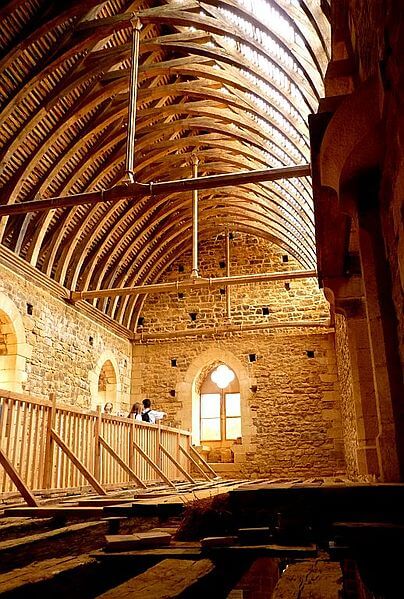

There's a castle under construction in France. Not a Disney-style castle at a theme park. An actual castle using medieval designs, materials, and construction methods.

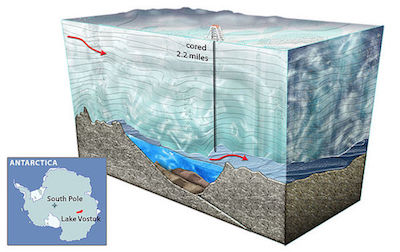

There's a castle under construction in France. Not a Disney-style castle at a theme park. An actual castle using medieval designs, materials, and construction methods. And just to make all this interesting, there's a magnetic anomaly in one end of the lake.

And just to make all this interesting, there's a magnetic anomaly in one end of the lake. Unfortunately, there are concerns that the antifreeze used to maintain the boreholes through the glacier might contaminate the lake, so scientists are proceeding with extreme caution. While the overwhelming majority of species they have found could quite likely just be contaminants from the surface, they have found at least one previously unknown species that might very well have come from the lake itself.

Unfortunately, there are concerns that the antifreeze used to maintain the boreholes through the glacier might contaminate the lake, so scientists are proceeding with extreme caution. While the overwhelming majority of species they have found could quite likely just be contaminants from the surface, they have found at least one previously unknown species that might very well have come from the lake itself.