The End of the VHS Loop

Maggie had me cleaning out the attic the other day, and I found a cardboard box filled with old VHS tapes. We hadn't used the VCR in something like a decade, but I managed to find it (in the garage, under five or six cans of paint) and hooked it up.

Maggie had me cleaning out the attic the other day, and I found a cardboard box filled with old VHS tapes. We hadn't used the VCR in something like a decade, but I managed to find it (in the garage, under five or six cans of paint) and hooked it up.

I went through some of our old home videos, and found that some worked perfectly fine and others didn't work at all. There didn't seem to be any real link between their age and how well they worked, either, so I decided to do some research.

There are lots of stories bouncing around the internet about how VHS tapes are supposed to stop working after ten years, or 15, or 20, but there doesn't seem to be any real consensus. People have written their anecdotes about all sorts of lifespans for the dumb things.

It turns out that there are a lot of reasons for the wildly different stories. First off, there was a lot of advertising done when DVDs came out—trying to convince people to switch from VHS to DVD, with the claim that VHS tapes wouldn't last very long.

And the conditions that cause the tapes to wear out vary wildly. VCR malfunction is the quickest cause, of course, but other factors include: rapid temperature swings, frequent use, low humidity, proximity to magnets and electronics, and storage conditions.

What makes it even more confusing is that many of the factors aren't even consistent. Infrequent usage can sometimes cause the tapes to fail, and frequent use can do the same thing.

What makes it even more confusing is that many of the factors aren't even consistent. Infrequent usage can sometimes cause the tapes to fail, and frequent use can do the same thing.

The last movie released on VHS was “A History of Violence,” in 2006. I doubt that a copy of this will be the last movie ever watched in the format, of course: by that time DVDs had pretty much taken over the whole scene, leaving very little of a VHS market remaining. The “last view” honor will most likely go to someone's home movie, and probably within the next 50 years.

Arecibo: Peering Out

Built in the early 60s, the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico is the largest radio telescope in the world, with a diameter of a thousand feet. It’s appeared in a James Bond movie, “Contact,” “The X-Files,” and any number of novels.

Numerous discoveries have been made from there, ranging from new knowledge about the planets in our own solar systems to the discovery of pulsars, the first planets outside our solar system and examinations of distant galaxies. Basically, I’m trying to say that it’s a really big deal.

Numerous discoveries have been made from there, ranging from new knowledge about the planets in our own solar systems to the discovery of pulsars, the first planets outside our solar system and examinations of distant galaxies. Basically, I’m trying to say that it’s a really big deal.

Much of the motivation for building the radio telescope was actually military based—it was used to discover Soviet radar installations during the Cold War by, get this: listening for Soviet radar waves bouncing off the moon.

Nonetheless, it has also been one of the most important scientific research installations on Earth for much of its life. One of the most famous programs run out of Arecibo is SETI, or the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Life, which analyzes data from the telescope to try and find any alien radio signals.

You can actually help with that through SETI@Home, a computer program that lets SETI use your computer remotely to help perform calculations. I’ve been running it for years.

In recent times, the observatory has faced significant funding troubles, though it is managing to hold on and continue performing a bunch of worthy scientific work.

If you’re ever in Puerto Rico, you can actually visit the radio telescope. Though you can’t enter the labs or the various work spaces, there is a visitor center that provides a view of the dish, and is filled with interactive displays and exhibits. I went there once; it was definitely worth the trip.

Here’s a fascinating gallery of photos from the construction of the Arecibo radio.

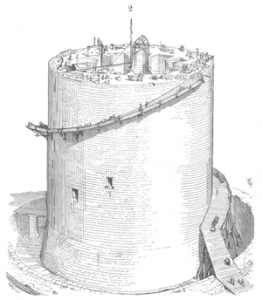

Castles in Decline

The decline of the castle can be summed up in one word: Gunpowder. Really seems a bit simple to just leave it there, so here goes:

The decline of the castle can be summed up in one word: Gunpowder. Really seems a bit simple to just leave it there, so here goes:

I generally avoid military history…always felt that people building things is more important to history than people destroying things. For any student of ancient architecture, though, castles are impossible to ignore.

Castles dominated Europe for more than 900 years. When someone thinks of the Middle Ages, castles are probably the first things on their mind.

There were two major types of castles. Not architectural types; I’m talking about the reasons the castles were built in the locations they were. Rural castles were the first type, generally placed in a location with some sort of important resource—fertile land, mines, mills, or maybe a major road or mountain pass.

The second type, urban castles, were built to control the local populace and maintain control over trade routes. All of them served as centers for administration and as the habitations of the nobility.

Castles were not the only medieval fortifications. There were plenty of different kinds of forts and garrisons and such. The key difference between castles and the other fortifications is that castles were actually used for administration.

Only a century after gunpowder gained common use did artillery grew to be a major threat to castles. From that point, the decline of the castle was not so swift as you might expect. People built a few good castles after this time, a few of them even constructed to resist artillery—massively thick walls packed with dirt, rubble, and other debris.

The true death knell actually wasn’t artillery actually destroying the castles by artillery. It was a loss of confidence in the castles. The nobility simply started moving out, into grand palaces and estates.

The fall of castles as the center of European life was one of the main reasons that larger standing armies became a necessity, and led to one of the bloodiest eras in European history.

Space Elevators: Going Up?

When it comes to getting into space, rockets are pretty much staircases at best. More like ladders, really.

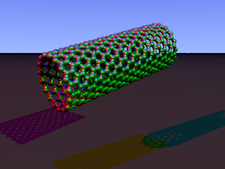

Space Elevator

That’s a bizarre thing to say, I know, but hear me out. Rockets are expensive and dangerous, but they’re still the best way we have of getting to space. (There are a couple of other ways, like Orion drives, but given that those things basically ride nuclear explosions…) There’s a theoretical method, that works much, much better: the space elevator. (Hence the staircase joke. Well, I thought it was funny, at least. So I’m not a professional comedian, so sue me.)

A space elevator is, essentially, a long cable—anchored at the equator, extending out into orbit. It works sort of like when you spin while holding a rope, and the rope is suspended above the ground by centrifugal force. (Or is it centripetal? I can never remember.) It’s not quite the same, of course, since it has to have a counterweight at the end, along with several other requirements.

Once the cable is up, cargo and passenger pods would be able to freely move up and down it, at much, much lower costs than rockets. Did I mention how expensive rockets are? Really, really expensive. As in: $10,000 to $25,000 per kilogram they need to lift. (For those of you who don’t have your measurement conversion tables memorized, one kilogram is equal to a bit more than two pounds.)

Carbon Tube

So why aren’t we using them now? Well, because we don’t have a strong enough cable. People keep bringing up carbon nanotubes as an option, but since we don’t have those yet, we just can’t build it.

The space elevator would be more than possible on other, smaller objects in the Solar System. We could build a space elevator on the moon with ordinary Kevlar.

Space elevators aren’t the only ideas for getting to space without rockets. Other ideas are floating out there, ranging from rocket sleds (which does actually involve rockets, but in a much more affordable manner) to skyhooks, which resemble something that a mad scientist, a six year old, and an engineer would design together if asked to create the nuttiest amusement park ride ever, all while hooked to caffeine IV drips.