Before the Pawpaw Goes Bad

A Moving Story About Food

I've written a lot about the shipping industry in this space. Everything from forklifts and pallets to roads. In fact, I write about roads almost more than anything else. One thing I don't write about so much is the actual stuff being shipped.

Shipping fresh food has been a goal of human civilization since…well, always. You can only maintain a certain level of population with food gathered in your local area. Agriculture increases the maximum potential population level, but only up to a point. The ability to ship food from other areas results in even higher potential populations. It also provides a safety buffer for times of famine. If one harvest goes bad, ship a surplus from somewhere else.

For a long time though, there weren't a lot of good ways to ship food. You could transport some grains, spices, and oils in decent ways. Fresh fruit and vegetables, however, were another matter. Meat could be shipped, but only if it was smoked or—more usually—salted.

The downside: these preservation processes resulted in lower nutritional quality. Scurvy was a risk on long sea voyages exactly because of this.

So, the average person's main diet was of food grown very near to him and her—usually within a few hours' walk. For larger distances, livestock had to be moved while still alive; hence those giant cattle drives in the Old West, and railroad cattle cars.

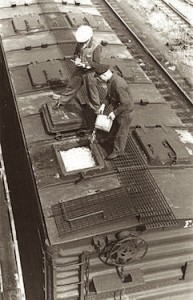

The refrigerator railroad car changed all that. Insulated cars had ice tanks at either end, with vents allowing the cooler air to flow into the cars to preserve meat and produce. This rapidly resulted in the practice of transporting various local foodstuffs across huge distances.

One interesting side effect of this is that many of the fruits and vegetables we eat today aren't necessarily the best tasting or most nutritious. They’re the ones most easily shipped and preserved. Many fruits are picked before they're entirely ripe. If you've ever had a ripe peach off the tree, you'll immediately be able to taste the difference. I won't eat grocery store peaches anymore if I can help it.

Pawpaws, a fruit native to the East Coast, are generally agreed to be one of the most delicious fruits you can find. (I can't stand them, but I've never met anyone who agrees with me on this.) Lots of folks use them in place of bananas in their cooking. Why aren't they sold in grocery stores everywhere? They bruise easily and only last a couple of days after being picked before going bad.

Getting There

About the Traveling Salesman Problem

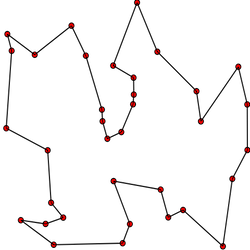

Let's say there's a traveling salesman trying to hit a certain group of towns during a week. (I know, I know: eCommerce is eclipsing the traveling salesman these days, but I’m Old School, so bear with me.) To save time, this traveling salesman wants to calculate the best possible route between all the cities—the route with the absolute shortest possible distance—before he returns to the starting city.

Let's say there's a traveling salesman trying to hit a certain group of towns during a week. (I know, I know: eCommerce is eclipsing the traveling salesman these days, but I’m Old School, so bear with me.) To save time, this traveling salesman wants to calculate the best possible route between all the cities—the route with the absolute shortest possible distance—before he returns to the starting city.

Sounds easy: just add up all the shortest distances between cities. Right?

Wrong.

In fact, if you tried the calculations on a home computer, the sun would have already devoured the Earth in its death-throes, billions of years in the future, by the time your computer finished the calculations. (The problem is actually what they call an NP-complete problem, and it’s really complicated, and it makes my head spin, and good luck.)

That's why Google Maps only optimizes routes with no more than ten waypoints in them because going beyond that just requires too much time and computing power. For those of us without the patience to wait billions of years, there are workarounds to the Traveling Salesman Problem.

A Solution to the Problem

One of the best ways is to use something called a genetic algorithm, which begins with a handful of random solutions to the problem…and usually ends up being terrible. So, it then tinkers slowly with each one, discarding all but the best solutions. Eventually, after enough cycles of this, the algorithm produces a route that, while not the absolute best, seems reasonable enough.

The practical applications of the Traveling Salesman problem should be obvious. To shipping companies alone, it represents a ton of time and money. Other industries that are concerned with it include semiconductor manufacturers and paper mills.

We also have a large number of variants in this challenge, including the appropriately named Traveling Politician Problem.

A New Old-School Castle

Or: Undraining the Moat

There's a castle under construction in France. Not a Disney-style castle at a theme park. An actual castle using medieval designs, materials, and construction methods.

There's a castle under construction in France. Not a Disney-style castle at a theme park. An actual castle using medieval designs, materials, and construction methods.

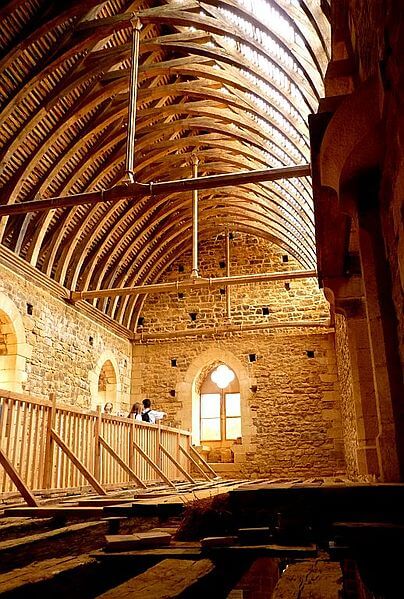

Guédelon Castle started construction in 1997 and won't be completed until sometime in the 2020s. The designers aim to create an authentic 13th century-style medieval castle.

Oh, and when they say authentic, they mean authentic:

- They only use local materials.

- The site for the castle was chosen very carefully, located near an old stone quarry, a pond, and right in the middle of a forest.

- All of the materials are gathered and hauled to the site using only medieval methods, including horse drawn carts.

- The construction workers all wear period-appropriate garb, use period-appropriate tools, and use period-appropriate construction methods.

- They have on-site blacksmiths, stone masons, carpenters, etc.

- No modern tools are used anywhere. Not even ramps; sorry, Yard Ramp Guy.

The project has created 55 jobs and attracted more than 200 volunteers. On-site professional training is provided to disadvantaged youth, some of whom have earned stone-masonry and other certifications. More than 300,000 tourists a year visit the project, and it is open to schools for educational purposes. The construction has definitely proven itself worthwhile in those regards, but none of those were the original intention.

This is all part of experimental archaeology, which reconstructs and uses ancient tools, structures, and artifacts and allows archaeologists to actually study which methods work best and produce results most like the actual artifacts.

One way they do that is by looking for construction quirks (not the actual scientific term they use). Anyone who uses a lot of tools knows that you'll end up with certain quirks in your project, depending on which tools you use. For example: the same cut will be slightly different with different saws. When you're using tools that aren't mass-produced like ours, those little quirks get magnified even more.

During experimental archaeology, you can look to see if the methods you are using produce quirks like the historical ones.

Experimental archaeologists have produced Iron Age farmsteads and Greek triremes, hauled Stonehenge sized stones, sailed from Peru to Polynesia on a raft (Kon-Tiki), and, of course, built Guédelon Castle. (For a longer list, check out THIS. It's an incredibly productive line of research. And a heck of a lot of fun.

Guédelon Castle is proving to be one of the most productive of these lines of research. We've learned tremendously about castle construction from it. There was actually a companion castle being built in America: the Ozark Medieval Fortress. It ran out of funding and is currently on hiatus. We still need that European vacation to see a castle under construction. With any luck, though, that will change.

_____

Photo By Ronny Siegel (Château Guedelon) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Tokyo Gets Drained

Flooding (you with) Information

There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel—is a flood water diversion facility.

There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel—is a flood water diversion facility.

“Enormous” might be an understatement. It’s more than 25 meters high and 177 meters long. The concrete room is held up by 59 immense, 500-ton concrete pillars. In addition to the main chamber, there are five huge underground silos, each 65 meters deep and 32 m in diameter. You could quite literally fit Godzilla in one of those.

Construction on it began in 1992 and didn't complete until 2009. The whole thing is essentially the world's largest drain. The silos and the Temple are linked by hundreds of miles of underground pipes. The entire complex is nearly four miles across.

Tokyo has suffered from frequent floods throughout its history—not just from heavy rain, but also from typhoons and tornadoes. G-Cans was built to withstand even the most massive, once-every-other-century floods. Its 14,000 hp turbines and 78 pumps are capable of pumping more than 200 tons of water per second into the nearby Edogawa River.

The architects and construction crew faced a number of major difficulties in the construction. Earthquake proofing was one of the biggest hurdles. Another: preventing buckling and sagging in the ground overhead as they dug out the complex; it is directly underneath a city, after all.

The architects and construction crew faced a number of major difficulties in the construction. Earthquake proofing was one of the biggest hurdles. Another: preventing buckling and sagging in the ground overhead as they dug out the complex; it is directly underneath a city, after all.

There was a little criticism about the steep price tag ($2 billion) and the fact that Tokyo already possessed significant flooding defenses. Still, given how prone to natural disasters the city is, I certainly think they made the right call.

So, they have the flood prevention thing covered. Of course, there are still earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, typhoons, Godzilla, and those horrifying giant Japanese hornets to worry about.