Maps and Oranges

When I have a choice of what map I want to use, I’ll always pick a globe.

Flat maps all have one major problem: they’re trying to display a round globe.

Here’s an experiment. Cut an unpeeled orange in half, then take out the insides without ripping the peel. Then try to push the peel flat on a surface.

Mercator Projection: 1569

Mapmakers have developed a number of strategies for dealing with the problem. They’re referred to as map projections, and the most commonly used is the Mercator Projection. It’s by far one of the most common map projections you’ll run into.

The Mercator Projection is quite useful and works great for navigation…but at the cost of grossly misrepresenting the size of certain landmasses, especially closer to the poles. The best way to picture this is by stretching out that orange peel. There’s going to be quite a bit of distortion.

Greenland is the biggest offender. Greenland in real life is 1/14th the size of Africa, and 1/3rd the size of Australia, but it is grossly inflated on the Mercator Projection and is actually portrayed as larger than Australia. Africa, meanwhile, is shrunk down until it appears the same size as Greenland on the map. This has actually produced quite a bit of academic and political controversy over the years. The Mercator is drifting out of popularity these days.

Another common map projection is the Goode homolosine projection. This one is the equivalent of cutting the orange peel to make it look flat; in fact, it’s often called the orange peel map. While the Goode homolosine projection does a much better job of representing the continents without distorting them, it does cut Greenland in half and, well… you can see what it looks like.

Given the choice, I’m always going to use a globe. Unfortunately, they’re less than perfectly portable.

The Semaphore Metaphor

Many inventions seem to arrive out of order. That is: considerably ahead of or behind where you’d expect them to show up. One of the best examples of this is the semaphore.

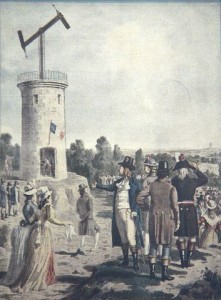

Early Semaphore

The semaphore was a long distance communication system invented in 1792 by the Frenchman Claude Chappe. It takes the form of a series of towers with clear lines of sight between them, with large pivoting arms on top. The arms are moved in a visual code, representing the individual letters, which the next tower in the line then repeats, and so on and so forth.

When it was invented, the semaphore was the fastest method of communication available at the time. There were quite a few limitations, of course: it didn’t work well (or really at all) at night or in bad weather, the towers were expensive to build, several were destroyed by angry mobs, and it required attendants at every tower, which drastically increased operating costs.

You could still send messages faster through the semaphore than by other method, and it saw considerable use for the next 50 years, until the electrical telegraph took its place.

It seems like the semaphore should have been invented much, much earlier. None of the technology was by any means too advanced for, say, the Roman Empire. It’s just swinging arms on a tower, after all, and they had plenty of gears and pulleys and the resources to develop a massive network of them, if they so chose. They had the math necessary to develop codes. There were even a number of Roman experiments in optical telegraphy. So why didn’t they build the semaphore?

The answer is actually pretty simple: telescopes. The Romans lacked the advanced optics necessary to build decent telescopes, which meant that semaphores would’ve been built much, much closer together, to the point where they would no longer be cost effective, even for the mighty Roman Empire.

Technological advancement isn’t conducted in a vacuum. Each new invention requires a network of other advances around it, making new tools, ideas, and techniques available to the inventors. This is not to say there’s a set order in which technology must be invented. Many of our technologies were not an inevitable development but, often, merely choices made for business or cultural reasons, or even out of convenience.

Our technology could have ended up radically different than it did…but it still would have built itself from the ground up.

The Flying Buttress

Everyone's seen flying buttresses. They're those huge pillars on the sides of European cathedrals. Notre Dame (the one in France completed in 1345, not the one with the football team) is among the most famous.

The Flying Buttress

Though they look like they wouldn't be good for much other than making sure that a wall doesn't fall over (sometimes used that way) and making grade school kids laugh, they're the only reason that buildings of that size were even possible in those days.

Flying buttresses actually help support the weight of the ceiling. Before flying buttresses, the walls had to be immensely thick in order to prevent the ceiling's weight from pushing the walls outward.

Flying buttresses form a natural arch with the roof, thereby taking much of the outward force generated by the roof's weight off the walls. This allows the walls to be built much thinner. And it also allows the inclusion of the immense windows in the walls that cathedrals are so famous for.

The construction of the buttresses was a difficult enough task in itself, of course. It first involved the construction of temporary wooden frames, or centering to be hoisted up between the wall and the column. The centering was what kept the arch of stones in the air while the mortar was drying, serving as the arch in the meantime.

Frequently, early cathedrals with flying buttresses were built with much thicker, closer, and more immense buttresses; the backers funding the construction weren't entirely convinced that they would actually work. Some of the buttresses were actually so huge that they blocked out much of the light coming in.

Even cathedrals with much, much thinner buttresses have lasted until today. And a building that lasts for 800 years does tend to speak for itself pretty well.

A Thrill on Potbelly Hill

One of the most interesting construction riddles out there is the archaeological site of Göbekli Tepe (Potbelly Hill) in southeast Turkey. Göbekli Tepe is one of the oldest dig sites on earth: dating back some 14 thousand years, it’s one of the oldest human constructions ever discovered.

It predates almost every single construction technique we know, not to mention the writing, metal tools, the wheel, agriculture, and even animal husbandry. This is a site built when we were still hunter-gatherers.

Göbekli Tepe

The site is largely buried. Only 5% of it is exposed, while the majority is still covered, and only known through geophysical surveys (essentially, underground sonar, though it’s more complicated than that). The site is covered with a tell, which is essentially a flat topped hill composed of disintegrated mud bricks and other building materials; the building site steadily gained in height as new constructions were built over old ones.

The site contains circles of enormous, T-shaped stone pillars fitted into sockets that are carved into bedrock. Most archaeologists believe the site to be a religious one, a burial site, or both.

One of the major conundrums regarding Göbekli Tepe is one of construction. How did a small, scattered population build a site this enormous and complicated? They didn’t have animals to haul the weights, or wheels. It seems likely that primitive versions of the techniques used to construct the Egyptian pyramids and Sumerian ziggurats were used, but it’s extremely difficult to say, since both were constructed closer to the present day than to the construction of Göbekli Tepe. It’s that old.

This has, of course, resulted in the usual ancient-aliens conspiracists coming out of the woodwork to plant their flag on more “evidence.” In actuality, it probably has more to do with the vastly different climate there at that time: it was a lush garden paradise, filled to the brim with game, fruit, nuts, and wild grains, allowing the population to concentrate their population more than other hunter gatherer sites and maintain a larger workforce.

But their specific construction techniques are still a subject of major interest to me, since this is very possibly the oldest archaeological site in existence.

_____