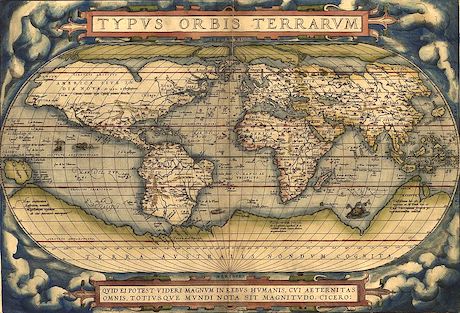

The Ortelius Theatrum

The world map from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum

These days you don't see atlases very often. Google Maps are just much more prevalent and often more useful. Atlases are unquestionably a direct ancestor of Google Maps, however. The oldest ever atlas? The Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, or “Theatre of the World.” (Sorry, no Greek mythology jokes for you today.)

Originally published in May 1570, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, was written by the mapmaker Abraham Ortelius (my favorite Brabantian). It contained a total of 53 maps, all bound together. Despite being a skilled mapmaker himself, all the maps included were from other mapmakers. (Though he frequently tidied them up a bit.)

Unusually for the time, Ortelius actually credited all 33 mapmakers in the bibliography. He also included a list of other quality mapmakers he knew in the back, which grew longer with every edition published during his lifetime.

Ortelius published 25 editions in his lifetime, the last of which contained 167 maps and was published in seven different languages. Naturally, I hold much admiration for someone who devoted such time and painstaking care to improve on such a singular undertaking. I’d like to think that Maggie thinks of my work on, say, the lawn, with such approval. Though Maggie might say otherwise.

(Confirming: Maggie just said otherwise.)

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum was hugely significant. Not only was it vital in pushing forward the navigational feats of the Age of Exploration, it also is considered to be the starting point for the Dutch Golden Age of Cartography, which lasted a solid century.

The maps included in Theatrum Orbis Terrarum were remarkably accurate for their time. Possibly even more importantly, it made geography accessible to the growing middle classes at the time, who hadn't been able to easily afford maps before this.

It massively improved the state of public education at the time, and made the world a more understandable and less mysterious place. That’s a good thing, right?

The Yard Ramp Guy®: Angling Ramps Into Warehouses

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy follows the flow of warehouse scenarios and eloquently shows that many of those streams run through yard ramps.

Check out his great piece HERE.