Or: What a Long, Strange Trip It’s Been

Less than half the parts in Chevy and GMC trucks are made in America.

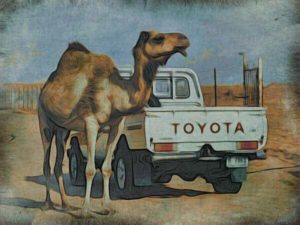

Made in American (not the camel)

The most American truck? The Toyota Tundra, made with more than 70% American parts.

I could make the obvious, cheesy joke about how a Japanese company is making the most American truck, but there’s a more important takeaway here. And it's starting to give us an idea how interconnected manufacturing and the modern global economy has become.

We hear a lot about globalization these days, mostly in terms of trade agreements like NAFTA. We also hear a lot of talk that treats globalization like it's some brand new phenomenon. Actually, globalization dates back (at least) to the Bronze Age. Yes, ancient societies were hardly isolated citadels surrounded by barbarians.

The Ancient Sumerian texts (some of the oldest in the world) fairly often referred to trade partners. We’ve managed to decipher some of these partnerships—including deals with ancient Middle Eastern states like Egypt.

We couldn’t match the name of one trade partner, Meluha, though, to a location until recent archaeological discoveries. As it turned out, Meluha is actually the Harappan civilization.

Also known as the Indus River Valley civilization, it was located in our modern-day India and Pakistan. Meluha was some 2,300 miles away from the Sumerians—a tremendous distance for this time period.

As time went on, the level of globalization only grew. We've found Roman coins in ruins from ancient India, and we know goods from as far away as China made it to Rome. Medieval Europe was chronically short on coinage, since all their silver was going to India and China.

(Europe had nothing India or China wanted, but India and China had all sorts of spices and such that Europe wanted.)

Apart from the Roman Empire, Europe was an unimportant backwater on the global scale until the Renaissance and the Age of Sail.

So, if anyone tries to convince you that globalization is something new, or that human history isn't one of perpetual interconnection, well...laugh. Laugh harder than you would have if I’d actually made some cheesy joke about a Japanese car company being more American than an American company.