The Value of Blue Blood

Nobility don't literally have blue blood, but horseshoe crabs do, and it's worth quite a bit of money—up to $15,000 per quart.

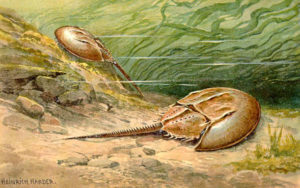

Horseshoe crabs are ancient critters. We actually consider them living fossils, in that they appear in the fossil record some 450 million years ago.

Though they're called crabs and look like crustaceans, they actually aren't; they're more closely related to spiders. Some species grow to around two feet long. They crawl around on shallow ocean bottoms in sandy and muddy areas, looking for worms and mollusks to eat. They've also been known to eat crustaceans and small fish.

Their blood is a deep, rich blue color due to the presence of hemocyanin—a chemical similar to hemoglobin that carries oxygen through the blood but uses copper instead of iron (which is what makes our blood red). Hemocyanin is somewhat more effective at carrying oxygen in cold, oxygen poor environments than hemoglobin, though hemoglobin is more effective overall.

What really makes the blue blood of horseshoe crabs valuable is how it reacts to disease.

I'm feeling a bit crabby myself.

Certain cells—called amoebocytes—in the horseshoe crab's immune system are extremely sensitive to bacteria and react by clotting around the infection in an inescapable lump. Pharmaceutical companies burst the cells to harvest coagulogen, the chemical that lets the cells do their thing.

The coagulogen can then be used to detect bacterial contamination in any substance that might come into contact with blood, even at levels as low as one part per trillion. This test has become the absolute standard: every single drug used in the country is required to be tested this way.

This isn't necessarily good for the crabs, though, and the species has also spent quite a bit of time being used as fertilizer and as bait. Over time, this has damaged the population quite a bit.

Though most of the crabs survive the bleeding process, some 15% die and others are rendered too lethargic to mate. All of which is pretty problematic, since they're harvested during mating season.

Scientists are working on an artificial replacement for coagulogen, but that might not help the crabs too much. When science perfects the artificial coagulogen, we’re likely to use our horseshoe crabs as bait.

The Rodney Dangerfield of anthropoids, they just don’t get any respect.

_________

Quotable

Oh, Yard Ramp Guy, replace “cranky” with “crabby,” and I still claim a blog-specific quotation here:

“I'm cranky.”

— Larry David

During the 1130s in China, the Son Dynasty employed heavy deployment of

During the 1130s in China, the Son Dynasty employed heavy deployment of