Don Justo, with Gusto

Don Justo at age 85

Some people’s work ethics are entirely too formidable. I'm by no means a lazy man, but sometimes even I like to relax and spend an entire day on the lake with a fishing pole.

Not Justo Gallego Martínez. Known also as Don Justo, he is a former monk, living in Spain, and he’s been building his own cathedral for decades.

After eight years of living in a Trappist monastery, he left the order due to tuberculosis. And he promised himself that he would build a shrine if he recovered. Don Justo started work on the cathedral in 1961.

Martínez's work begins each morning at 6 AM and lasts for about ten hours a day. He takes off only on Sundays. He has missed but a handful of days during the decades of the cathedral’s construction, and he’s done the vast majority of the work completely alone, though he does have a helper these days.

When he started, there was no plan. He just leveled the ground and started building. To this day, he regularly changes the design, according to inspiration or whim. The cathedral doesn't have any planning permissions from the city of Mejorada del Campo, nor does it have the blessing of any part of the Catholic Church.

Despite the lack of city permissions, Don Justo hasn't had to deal with any real trouble from the city. Most residents are quite proud of it, though a small number consider it an eyesore.

Despite the lack of city permissions, Don Justo hasn't had to deal with any real trouble from the city. Most residents are quite proud of it, though a small number consider it an eyesore.

Most of the materials he uses for construction are recycled. Local construction companies and a nearby brick factory frequently donate excess material to the project. Frequently, he also folds everyday objects into the design. For example, he molded his columns with old oil drums.

I've thrown up a few sheds in my life, but a whole cathedral? I don't have a fraction of the ambition to handle that. And then there’s Don Justo, who doesn't even use a crane. And he's 90 now. Not for me.

_________

Quotable

That other Yard Ramp Guy keeps on quoting, and, I must say, his choices are pretty good, if a bit too tilted toward sports. Oh, well. As Michael Jordan said, “Just play. Have fun. Enjoy the game.” So, en garde, Yard Ramp Guy:

“If opportunity doesn’t knock, build a door.”

— Milton Berle

The second car I ever owned was a used

The second car I ever owned was a used

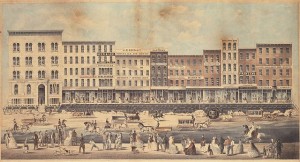

Nineteenth century Chicago was plagued by, well, plagues. Epidemics of typhoid fever, dysentery, and cholera repeatedly hit the city. The 1854 cholera outbreak killed six percent of the entire city's population.

Nineteenth century Chicago was plagued by, well, plagues. Epidemics of typhoid fever, dysentery, and cholera repeatedly hit the city. The 1854 cholera outbreak killed six percent of the entire city's population. In 1856, an engineer named

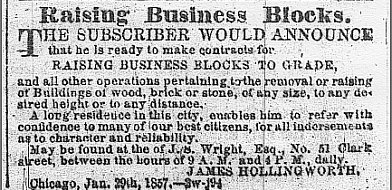

In 1856, an engineer named  Only masonry buildings were considered worth raising; they placed wood-framed buildings on large rollers and moved them to the outskirts of town, usually without even bothering to empty out the furniture first.

Only masonry buildings were considered worth raising; they placed wood-framed buildings on large rollers and moved them to the outskirts of town, usually without even bothering to empty out the furniture first.