Archives: Cable is the Real Web

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: Cable...is what's for dinner. And breakfast. And brunch. And lunch.

Cable: The (wet) Connection

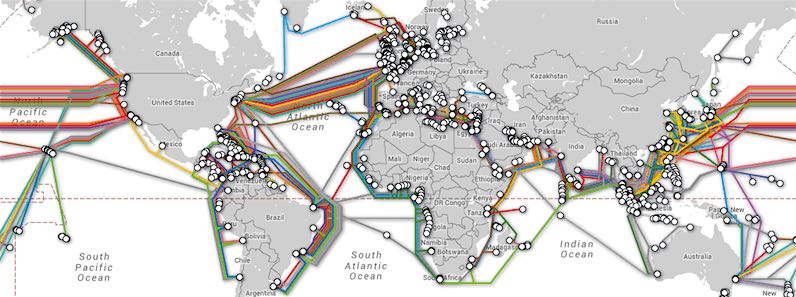

I've heard everyone—from my coworkers to the news outlets—describe ours as a wireless society. Nothing could be further from the truth.

A fun little statistic: In 2006, we transmitted less than one percent of all international data traffic via satellite. The percentage is a little higher today, but we continue to route the overwhelming majority of data through undersea fiber optic cables that stretch between every continent except Antarctica. Countries around the world consider them absolutely vital to their economies.

We've been laying underwater cable for a long time. Those first put into service were telegraphy cables, laid in the 1850s, though experimentation with the cables went back as far as the early 1840s (just a couple years after the invention of the telegraph). And during the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union tapped into and cut each others' cables.

Laying the cables today is immensely expensive. We spend billions of dollars each year on the process. And, while the cost has gone down a bit, it's still normal to see price tags hitting tens of thousands of dollars per mile.

Submarine cables also break, and they break frequently. Fishing trawlers, anchors, earthquakes, turbidity currents (giant underwater landslides), and shark bites are all major causes of these breakages. We're not entirely sure why sharks like biting them so much.

Repairing them is a difficult and costly process, involving specialized repair ships that lower grapples to lift the broken ends of the cables to the surface for repair. We employ different types of grapples, depending on the seafloor around the break (for example: rocky vs. sandy). In shallower waters, we can use submarines to repair the cables.

Politicians thrive on producing drama about literally anything. While drama over oil and such tend to hog most of the media attention, submarine cables are a really big deal.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: The Steel Surge

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy explains how he manages to keep pricing comparatively low, even with the recent and "sudden" steel surge.

Click HERE to read another example of The Yard Ramp Guy's terrific reputation in the industry.

Archives: Raising a City

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: It turns out that buildings can be very moving experiences.

Stay with me on this one: yes, it begins on a pretty sour note…but I promise you there’s a happy ending.

Raise High the Roof Beams, Carpenters

Nineteenth century Chicago was plagued by, well, plagues. Epidemics of typhoid fever, dysentery, and cholera repeatedly hit the city. The 1854 cholera outbreak killed six percent of the entire city's population.

The reason for those diseases, and a common culprit throughout history: poor-to-nonexistent drainage. Standing water in a city makes a perfect breeding area for all sorts of nasty illness. In fact, disease historically was so bad that the majority of medieval cities experienced negative population growth—more people died of diseases than were born.

The only reason cities didn't depopulate was a near constant influx of immigration from the country. This changed steadily around the world when city infrastructure and medicine improved. Disease was still quite common in the 19th century, but Chicago's level of disease was quite unusual in an American city for the time.

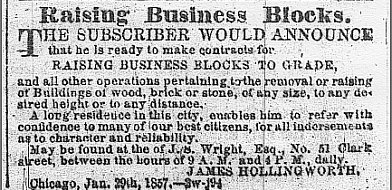

In 1856, an engineer named Ellis S. Chesbrough developed a plan for a city-wide sewer system that would solve the problem. It was unusually ambitious: he wanted to raise the entire city six feet, then build sewers below the newly raised buildings.

In 1856, an engineer named Ellis S. Chesbrough developed a plan for a city-wide sewer system that would solve the problem. It was unusually ambitious: he wanted to raise the entire city six feet, then build sewers below the newly raised buildings.

Sounds insane, right? That's what I thought, too, except they actually did it—raising the first building in January 1858: a four-story, 70 foot long, 750-ton brick structure lifted on two hundred jackscrews to its new level, without the slightest damage. Engineers boosted more than 50 masonry buildings that year alone.

In 1860, a team of engineers actually managed to raise up half a city block in one go—an estimated 35,000 tons lifted nearly five feet into the air by 600 men using 6,000 jackscrews. They were so confident in the process that businesses didn't even close during the the five days it took to lift the whole thing.

On the last day of the process, before they began work on the new foundations, they allowed crowds to walk underneath the buildings, among the jacks. At another point, a six-story hotel was raised up without the guests even realizing it.

Only masonry buildings were considered worth raising; they placed wood-framed buildings on large rollers and moved them to the outskirts of town, usually without even bothering to empty out the furniture first.

Only masonry buildings were considered worth raising; they placed wood-framed buildings on large rollers and moved them to the outskirts of town, usually without even bothering to empty out the furniture first.

This was so common that, for quite a few years, people considered looking out the window to see a building going past just another day of normal traffic.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Angling Yard Ramp Strategy

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy riffs on Yogi Berra's great quotation: "When you come to a fork in the road, take it."

Click HERE to see what direction The Yard Ramp Guy chose to take.

Archives: Evolution of the Screw

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so, my From the Archives series. This week: Turn, turn turn: the evolution of the screw.

Screws are a magnificent invention. I've talked about them plenty – think of them simply as ramps wrapped around an axle – so why wouldn't I be interested? They’re simple machines and they literally help batten down the hatches. I figure it’s time to unscrew the lid on their history.

Our old friend Archimedes probably invented the screw. Archimedes' screw is used to pump water uphill, usually for irrigation, through a tube with a metal screw inside: as you turn the screw, the threads scoop up water and push it to the top.

Archimedes' screw

Interestingly enough, we still commonly use this device, and also turn it in the opposite direction. In the Archimedes turbine, water flowing downward turns the screw, which itself is the center of a hydroelectric generator.

Within a few centuries of their invention, screws were appearing all around the Mediterranean in the form of wooden screw presses. We used these to smash olives for olive oil and to smash grapes for wine — both major products of the region. Later on, the screw press would also be a vital component of Gutenberg's printing press.

Me, rummaging for my turnscrew.

Have you noticed a pretty major use that's missing here?

That's right: screws weren't used as fasteners. Instead, there were nails, welding, dowels and pins, etcetera, etcetera. This list of “alternatives” is substantial. In fact, we didn’t use screws as fasteners for nearly two millennia after Archimedes invented them.

What was missing? The screwdriver. (Fun fact: we used to call screwdrivers “turnscrews.”) We didn’t invent the screwdriver until the 1500s. Even then, we rarely tended to use screws as fasteners.

The final piece of the puzzle? The creation of machine tools necessary for manufacturing metal screws. Until that happened, they were just too much trouble to produce in large quantities.

Since we optimized that production angle, we haven't stopped turning them out.

______

Archimedes' screw gif by Silberwolf (size changed by: Jahobr), CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: State Ramp Coverage

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy explains how Alaska, aka The Last Frontier, is not that at all, so far as yard ramp coverage is concerned.

Click HERE to boldly go where no Yard Ramp Guy ramp has gone before.

Archives: Space Elevators

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so, my From the Archives series. This week: The ups and downs of space elevators.

When it comes to getting into space, rockets are pretty much staircases at best. More like ladders, really.

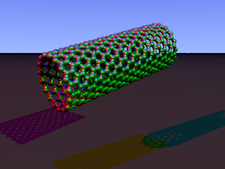

Space Elevator

That's a bizarre thing to say, I know, but hear me out. Rockets are expensive and dangerous, but they're still the best way we have of getting to space. (There are a couple of other ways, like Orion drives, but given that those things basically ride nuclear explosions...) There's a theoretical method, that works much, much better: the space elevator. (Hence the staircase joke. Well, I thought it was funny, at least. So I'm not a professional comedian, so sue me.)

A space elevator is, essentially, a long cable—anchored at the equator, extending out into orbit. It works sort of like when you spin while holding a rope, and the rope is suspended above the ground by centrifugal force. (Or is it centripetal? I can never remember.) It's not quite the same, of course, since it has to have a counterweight at the end, along with several other requirements.

Once the cable is up, cargo and passenger pods would be able to freely move up and down it, at much, much lower costs than rockets.

Did I mention how expensive rockets are? Really, really expensive. As in: $10,000 to $25,000 per kilogram they need to lift. (For those of you who don't have your measurement conversion tables memorized, one kilogram is equal to a bit more than two pounds.)

A Carbon Tube

So why aren't we using them now? Well, because we don't have a strong enough cable. People keep bringing up carbon nanotubes as an option, but since we don't have those yet, we just can't build it.

The space elevator would be more than possible on other, smaller objects in the Solar System. We could build a space elevator on the moon with ordinary Kevlar.

Space elevators aren't the only ideas for getting to space without rockets. Other ideas are floating out there, ranging from rocket sleds (which does actually involve rockets, but in a much more affordable manner) to skyhooks, which resemble something that a mad scientist, a six year old, and an engineer would design together if asked to create the nuttiest amusement park ride ever, all while hooked to caffeine IV drips.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Steel Evolution

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy impressively shows us how words matter in influencing hearts and minds.

Click HERE to read those words.