Archives: Taking the Road Train

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: how do you spice up long, desolate roads? With road trains, of course.

All Aboard...

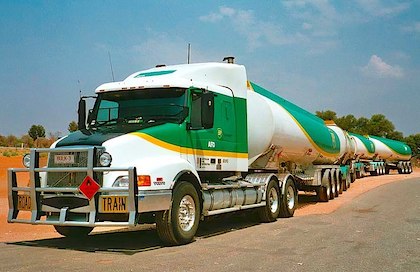

Anyone who spends a lot of time road tripping has likely seen a road train, a semi truck with more than one trailer behind it. They only receive so much use here in the United States since they are difficult and dangerous to drive. Plus, they're usually limited to just two trailers.

If you want to see the really big road trains, you need to head south. A lot farther south.

Australia is the birthplace of the road train, where they first appeared in the Flinders Range of South Australia in the mid 1800s, pulled behind traction engines, giving them a much more train-like appearance.

Today, Australia still uses more road trains than the rest of the world combined—and for good reason. Australian roads are some of the longest and most desolate in the world.

The overwhelming number of consumer cars and trucks we manufacture today are not capable of traveling between service stations in many parts of Australia on a single tank of gas. If you don't plan carefully, you WILL get stranded.

It's generally just a much better idea to fly wherever you're going. (Which most people do.) If you do decide to road-trip, though, you'll spend ages on the road without seeing anyone, followed by a massive road train almost knocking you off the road with the wind from its passage.

And it doesn’t stop there. Double road trains aren't a particularly big deal in Australia. The really impressive ones are the triples and quadruples. You'll want to just pull off the side of the road when one gets near. These are the biggest and heaviest road-legal vehicles in the world, often pushing 200 tons. (There are much, much bigger ones, like the Bagger 288, but they're certainly not road-legal.)

While dangerous, these cost-effective road trains have been vital to the development of many remote Australian regions.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: On Price Points

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy honors English majors everywhere and makes sense of the roller coaster that is steel pricing.

Click HERE to watch him juggle.

Archives: Doing the Marengo

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: can limestone caves save the human race?

A kids' version of the man cave?

Marengo Cave is an enormous, beautiful natural cave in Indiana. It's easily traversable for tourists, isn't particularly muddy or wet, and is absolutely beautiful.

A group of children discovered the cave in 1883, and the townsfolk—immediately recognizing a potential tourist attraction—quickly declared it a protected site. A few years ago, Marengo Cave was declared a US National Landmark.

It's not the only cave in Marengo, Indiana, though.

The Marengo Warehouse is an old underground limestone quarry located just a few miles away from Marengo Cave. Opened in the 1800s, it contains almost four million square feet of storage space (more than 100 acres), about a quarter of which is in use. The owners converted it from a mine to a storage warehouse in response to competition from much larger limestone quarries.

All sorts of rumors swirl around the warehouse. For example, the Center for Disease Control supposedly stored supplies there for a long time, but the only actual government property inside are some 10 million MREs. The other contents of the warehouse include 400,000 tires and some 23 million pounds of frozen fruit, most of which are intended for use in yogurt.

The Marengo Warehouse is nowhere near unique. All around the world, we’ve converted limestone mines into storage spaces and business parks. This depends on how we mine the limestone. Since the 1950s, miners have worked carefully to ensure that the leftover space is actually useful, carefully removing 12-foot thick chunks of stone in grid-shaped patterns. When mining is completed, very little construction is needed to ready a cave for other purposes.

Me…in my man cave.

The underground limestone quarries are extremely stable. Limestone is made of compressed, ancient, tiny seashells. It's three times stronger than concrete, and has been used in construction for more than three thousand years.

Of course, there are certain concerns with use of the quarries. Ventilation is a much greater concern than in other mines, so electric forklifts are generally required instead of those powered by propane powered. And, while the older quarries are generally extremely stable, the geological strata above and below the facility must be monitored, to watch for shifting or cracking rock layers.

Now, I’m way too hopeful a man to get all bothered by doomsday scenarios, but if you really want to start preparing for all possibilities, those limestone caves might one day save the human race. I’ll stick to my man cave…when Maggie lets me, of course.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Advanced Warehouse Planning

Just when I finished spring cleaning: this week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy shows us the benefits of planning now for the end of the year.

Click HERE to watch him juggle.

Archives: Getting to the Cashews

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: Some nutty blog entry.

That's me, looking for cashews.

Anyone who's worked in shipping—or anyone who has ever opened a jar of mixed nuts—has experienced the same thing, over and over again: When you're moving a jumble of little stuff, the big items (or Brazil nuts) always end up at the top.

At first glance, it seems simple enough: the smaller stuff can just fit down into the holes between everything else. Problem solved. Except...if that were true, then the small stuff would be at the bottom but the big stuff would still be scattered all the way through.

Well, what about density? If the big items are just less dense, they'd pop right to the top, yes? Well, sometimes, though much denser large objects also tend to rise to the top. It's only the items with a slightly different-than-normal density that remain scattered throughout.

In order to understand this, we need to view it a bit differently. Let’s approach it in terms of convection. In a liquid, temperature and pressure differentials can create convection currents that move particles around in huge looping patterns. If you treat the mixed nuts as a fluid, convection actually starts to accurately model what's going on. (Scientists call it granular convection.)

As it turns out, both of our previous ideas were almost right. As we move the box around and shake its contents, we force the particles in the middle upward in a current. The particles on the sides then fall into the gaps left by the rising particles in the center. Which is where our first idea comes into play: the smaller particles can fit down into the new gaps more easily, leaving the biggest ones on top.

Found 'em.

We still have the density issue confusing things, though. And this we can't solve quite as easily. We know what happens, and we have an idea how it happens (weirdly enough, density doesn't particularly affect granular convection on this scale if the mixture is in a vacuum), but we still haven't put our fingers on all the whys.

One thing is for sure, though: Cashews are definitely the best. You'd have to be a fool to think otherwise. (Well, the almonds can stay, too.) Brazil nuts and all the rest are just something you have to endure for the sake of the cashews.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Industrial Juggling

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy describes delivering ramps in seven states. At the same time.

Click HERE to watch him juggle.

Archives: Cable is the Real Web

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: Cable...is what's for dinner. And breakfast. And brunch. And lunch.

Cable: The (wet) Connection

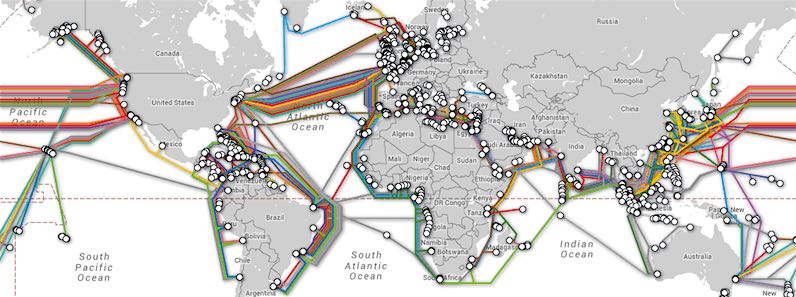

I've heard everyone—from my coworkers to the news outlets—describe ours as a wireless society. Nothing could be further from the truth.

A fun little statistic: In 2006, we transmitted less than one percent of all international data traffic via satellite. The percentage is a little higher today, but we continue to route the overwhelming majority of data through undersea fiber optic cables that stretch between every continent except Antarctica. Countries around the world consider them absolutely vital to their economies.

We've been laying underwater cable for a long time. Those first put into service were telegraphy cables, laid in the 1850s, though experimentation with the cables went back as far as the early 1840s (just a couple years after the invention of the telegraph). And during the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union tapped into and cut each others' cables.

Laying the cables today is immensely expensive. We spend billions of dollars each year on the process. And, while the cost has gone down a bit, it's still normal to see price tags hitting tens of thousands of dollars per mile.

Submarine cables also break, and they break frequently. Fishing trawlers, anchors, earthquakes, turbidity currents (giant underwater landslides), and shark bites are all major causes of these breakages. We're not entirely sure why sharks like biting them so much.

Repairing them is a difficult and costly process, involving specialized repair ships that lower grapples to lift the broken ends of the cables to the surface for repair. We employ different types of grapples, depending on the seafloor around the break (for example: rocky vs. sandy). In shallower waters, we can use submarines to repair the cables.

Politicians thrive on producing drama about literally anything. While drama over oil and such tend to hog most of the media attention, submarine cables are a really big deal.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: The Steel Surge

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy explains how he manages to keep pricing comparatively low, even with the recent and "sudden" steel surge.

Click HERE to read another example of The Yard Ramp Guy's terrific reputation in the industry.