Archives: The Amazing Spider, Man

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so, my From the Archives series. This week: spider silk!

Oh, What a Tangled Web We Weave

Another Busy Day at the Office?

If you're not a fan of spiders, you may want to skip this one. Otherwise, I just might’ve already snared you:

Spider silk is one of the most magnificent substances in nature, and there are a ton of different types of spider silk.

The silk can be used to capture prey. Along with their classic web-shaped design, spiders build webs in orbs, tangles, sheets, lace, and domes. One type of spider even lowers single-strand webs to go fishing.

Spiders tie up their prey in webs; a few species actually have venomous webs they use for this purpose. Other spiders produce extremely lightweight webs for “ballooning”—spiders blown along for dozens or even hundreds of miles by the wind, often in enormous swarms. (Yay, Australia!) Others use silk to lay trails to and from their web, and create alarm lines with it.

On top of that, spiders usually are capable of creating multiple types of silk—up to seven types in a single species.

Humans have studied and adapted countless different uses for spider silk. The spider-silk protein is comparable in tensile strength to high-grade alloy steel at one-sixth the density. We have stronger materials, like Kevlar, but none nearly so lightweight. (The strongest spider silk variety is more than ten times stronger than Kevlar.)

Spider silk is extremely stretchy and ductile, retaining its useful properties across a huge temperature range. The silk even makes for excellent bandages, due to its antiseptic qualities, and contains high amounts of vitamin K, which is useful in clotting blood.

Yes, the stuff that spiders spin is extremely useful. So, why don't we use it industrially? Because spider-farming doesn't work. Spiders eat each other. Instead, we've turned to genetic engineering. We've tried altering silkworms, E. Coli, goats (they produced it in their milk), tobacco plants, and potato plants to produce the protein.

We haven't mastered silk well enough to mass-produce, yet, but it'll happen eventually. (And then we'll get spider-web suspension bridges. Completely not creepy!)

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog / A Yard Ramp Guy Primer

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy describes how his company rents, sells, and buys new and used yard ramps throughout the United States. It's quite detailed and fascinating.

Click HERE to read the impressive scope of his operation.

Archives: The Kessler Cascade

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so, my From the Archives series. This week: proper waste disposal is important, even in space.

Or: In Space, No One Can Hear You Take Out the Trash

My family goes to a lot of movies. We're not film buffs, by any means. Usually, we're looking for snappy dialogue and explosions.

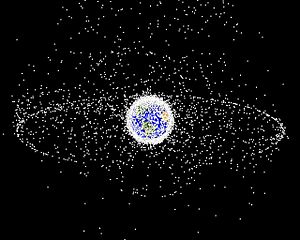

A couple years ago, we saw the film “Gravity.” For those who haven't seen it, a runaway debris cloud destroys satellites and space stations. Even though the science in that movie was pretty badly off, in a lot of ways, something like it does have the potential to occur.

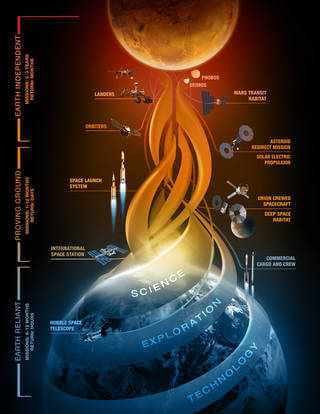

Kessler Syndrome is a hypothetical scenario dreamed up by a NASA scientist named Donald Kessler in the 70s. Essentially, it proposes that if enough objects are in low Earth orbit, collisions between them will eventually result in an enormous cascade of debris.

It's a pretty simple process: one piece of space junk slams into another, which sends debris scattering about.

Some of that debris hits another piece of space junk, creating another burst of debris, which slams into more space junk, and then maybe into a satellite.

Eventually, you have an enormous cloud of debris traveling through orbit. Each piece would be widely spaced, but even tiny bits can have insanely destructive power when moving that quickly. The cloud wouldn't take out every satellite, of course; it would stay in the same orbit, and many satellites would be in a higher or lower orbit.

A Kessler cascade could potentially make space travel impossible for millennia, completely blocking off that orbit. The debris wouldn't orbit forever. The drag from the miniscule amount of air at that altitude, along with a few other factors, would eventually clear the orbit again, though the process could take thousands of years.

Governments take the threat quite seriously. Satellites aren't allowed to launch unless they can be safely disposed at the end of their lifespans. The two most common techniques for doing so: dropping it back into the atmosphere or raising it up into a higher graveyard orbit.

People also have proposed gadgets for clearing the debris, including a device called a laser broom, which is precisely as cool as it sounds.

It all really just goes to show: proper waste disposal is important, no matter where you are.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog / Eric Aguilera: Into The Mix

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy welcomes Eric Aguilera to the team. He worked on the space shuttle. And he spells his last name just like Christina Aguilera does. So, I'm confident with this new addition to the fine team.

Click HERE to read all about Eric.

Archives: The VHS Loop

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so: my From the Archives series. This week: ah, that VHS technology has me all holiday-nostalgic.

The End of the VHS Loop

The End of the VHS Loop

Maggie had me cleaning out the attic the other day, and I found a cardboard box filled with old VHS tapes. We hadn't used the VCR in something like a decade, but I managed to find it (in the garage, under five or six cans of paint) and hooked it up.

I went through some of our old home videos, and found that some worked perfectly fine and others didn't work at all. There didn't seem to be any real link between their age and how well they worked, either, so I decided to do some research.

There are lots of stories bouncing around the internet about how VHS tapes are supposed to stop working after ten years, or 15, or 20, but there doesn't seem to be any real consensus. People have written their anecdotes about all sorts of lifespans for the dumb things.

It turns out that there are a lot of reasons for the wildly different stories. First off, there was a lot of advertising done when DVDs came out—trying to convince people to switch from VHS to DVD, with the claim that VHS tapes wouldn't last very long.

And the conditions that cause the tapes to wear out vary wildly. VCR malfunction is the quickest cause, of course, but other factors include: rapid temperature swings, frequent use, low humidity, proximity to magnets and electronics, and storage conditions.

What makes it even more confusing is that many of the factors aren't even consistent. Infrequent usage can sometimes cause the tapes to fail, and frequent use can do the same thing.

What makes it even more confusing is that many of the factors aren't even consistent. Infrequent usage can sometimes cause the tapes to fail, and frequent use can do the same thing.

The last movie released on VHS was “A History of Violence,” in 2006. I doubt that a copy of this will be the last movie ever watched in the format, of course: by that time DVDs had pretty much taken over the whole scene, leaving very little of a VHS market remaining. The “last view” honor will most likely go to someone's home movie, and probably within the next 50 years.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Your Holiday Ramp Cheer

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy dusts off the power of the pen, much mightier than the sword, and scribbles a great poem in tribute to the much, much mightier yard ramp.

Click HERE to get yourself well-versed.

From the Archives: Kitchen Marvels

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so: my From the Archives series. This week: the marvels of technology can readily be found in your very own kitchen.

The Modern Kitchen

The history of technology we usually teach kids is a flashy one. They hear about atomic bombs, rocket ships, computers. If it's big, shiny, immensely expensive and difficult to create, oh, and explodes, we teach them about it. Occasionally, we might mention a really important, yet more boring one, like nitrogen fertilizers. But generally? It's shiny objects all the way down.

Modern nitrogen fertilizers, are, in my book, the most important invention of the 20th century. Forget computers, forget atom bombs: nitrogen fertilizers are what allow us to maintain our global population levels—and they might get a few sentences in your average grade school history book.

When you look at even less-flashy inventions, they get less and less in the way of attention paid to them. In fact, I can almost guarantee that you never think about one of the categories of devices you use most often. Kitchenware.

Seriously. Go in your kitchen right now, and pick up…let's say, a rubber spatula. We've had rubber for much, much longer than we've had rubber spatulas, so why did we invent them? Well, you probably have a non-stick pan, right? Try scraping it out with a metal spatula, and you're going to scrape off the non-stick coating. (Which, apparently, is really bad for your health.)

Or take a look at cast iron pans. They've got a bit of a reputation for being a little on the tough side to clean, right? Well, they used to be considerably easier to clean, but as they drifted a bit more out of popular use (though never went completely absent), a final step of the production process was dropped. They used to be sand casted, then given a strong polish, but this polishing step was dropped to save on costs, so antique cast iron is actually considerably more non-stick.

Every single pot, pan, knife, item of silverware, or bizarre back-of-the-drawer gizmo in your kitchen has an extensive history all its own. And even a cultural context: five centuries ago, a muffin pan would have been pretty much useless scrap, thanks to the lack of common closed range stoves. These are tools that you use constantly and are personally relevant every day. Atom bombs? They can, really, only be personally relevant once.

__________

Photo by Todd Ehlers from McGregor, Iowa, a Mississippi River town, U.S. of A. (1937 Kitchen--Not Bad!) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Ramping Toward 2021

My friend The Yard Ramp Guy puts a noble spin on the year that was, and he looks forward to putting it all behind us.

Click HERE to review the world with him.