The Missouri-China Connection

Plus: Mud as a Preservative

One of my favorite museums is the Arabia Steamboat Museum in Kansas City, MO. The museum has one of the largest collections of pre-Civil War American artifacts in the world, and it's almost all from the wreck of the Arabia, a paddlewheel steamboat that sank in 1853.

The Arabia was discovered in 1987 by two families that risked everything they owned in their search. Because the Missouri river has shifted over time, they located the Arabia a half-mile away from the river. Excavation began in 1989. Mud preserved the ship almost perfectly.

Artifacts from the Arabia fill the entire museum, which is a huge place that still feels cramped from the size of the collection. The crown jewel of the museum is the actual paddle wheel and driveshaft—and not just sitting there, either. They're both kept in constant motion, though not by the original engine.

While America of the 1800s has a good claim for being the golden age of paddle boats, their use stretches much, much further back in time…and so, naturally, we travel now from Missouri to China.

During the 1130s in China, the Son Dynasty employed heavy deployment of paddlewheel boats. They weren't steam powered, obviously, but instead driven by pedaled treadmills. Even in the 1130s, paddlewheels weren't new; they'd been in use for a long time, but Yue Fei, the Song general, took them to an entirely new level.

During the 1130s in China, the Son Dynasty employed heavy deployment of paddlewheel boats. They weren't steam powered, obviously, but instead driven by pedaled treadmills. Even in the 1130s, paddlewheels weren't new; they'd been in use for a long time, but Yue Fei, the Song general, took them to an entirely new level.

These river-faring paddle ships could carry hundreds of soldiers and sailors, were armor plated, were propelled by up to 24 paddle wheels, and utterly dominated the rivers. The largest of them were armed with immense derricks, capable of swinging wrecking irons against other ships and shore-mounted fortifications, along with deck-mounted trebuchets capable of firing incendiary shells and smoke bombs.

Such ships remain utterly unique in the history of the world. No other civilization has built anything like them. And these weren't the last experiment with paddle-driven warships in China. While the Mongols were besieging a pair of cities linked by a huge pontoon bridge, paddle ships were in ample use by both sides. The Chinese defenders used an immense, hundred-strong fleet of paddle ships to run the blockade, while the Mongols created paddle ships with immense circular saw blades attached to them to cut through the bridge.

This sounds absolutely like something out of a cartoon, but it really worked.

_________

Quotable

Oh, Yard Ramp Guy, paddle around this one:

“You don't paddle against the current, you paddle with it. And if you get good at it, you throw away the oars.”

— Kris Kristofferson

Games People Play

A Grumpy Approach

Do I look like I'm playing games?

When I was a little kid, I hated board games. Absolutely did not like them. Especially Monopoly.

Risk I could tolerate about once or twice a year. Chess and checkers I could tolerate. That was the extent of the games we had (so maybe my choices were too limited). On rare occasions, I'd get to try a game someone else owned, but there weren't a lot out there (so maybe I come from a place where people didn’t play board games).

Things stick with us. These days, I’m surprised every time I see someone's board game collection (so maybe everyone’s not like me).

We're in a veritable board game renaissance right now. Most estimates put the number published each year in the thousands.

Of course, a huge chunk of these games are still terrible. Many are incredibly complicated and take hours—or even days—to play. Which, I suppose, is just fine for those with that kind of free time, but most of us don't have such free time. Other games are spat out quickly…or are just mediocre rip-offs of another game.

Bored.

Still, and muffling my rant just a bit, there are probably a gaggle of good new games published every year.

I’ve picked up a few over the years that I've grown to like, mostly for my kids and grandkids. My favorite is one I bought for my grandkids: Master Labyrinth. I still drag it out whenever they come over, and I'm probably more excited to play it than they are.

While I was reading about board games, I decided to hunt down the oldest.

Senet, Backgammon and The Royal Game of Ur are more than 4,000 years old. Go is about 2,500 years old, and Parcheesi is nearly 2,000. Tafl, a Viking ancestor of chess, is some 1,600 years old.

Yes. Humans have been playing games for fun for a long, long time. For better or worse. Mostly worse, I say.

This isn't just an old man rambling on and on about board games. Because I refuse to admit to being old…until I retire.

_________

Quotable

Oh, Yard Ramp Guy, still on topic with a quotation:

“I can see how he (Sandy Koufax) won twenty-five games. What I don’t understand is how he lost five.”

— Yogi Berra

Doing the Marengo

All About Limestone & Caves

Marengo Cave is an enormous, beautiful natural cave in Indiana. It's easily traversable for tourists, isn't particularly muddy or wet, and is absolutely beautiful.

Marengo Cave is an enormous, beautiful natural cave in Indiana. It's easily traversable for tourists, isn't particularly muddy or wet, and is absolutely beautiful.

A group of children discovered the cave in 1883, and the townsfolk—immediately recognizing a potential tourist attraction—quickly declared it a protected site. A few years ago, Marengo Cave was declared a US National Landmark.

It's not the only cave in Marengo, Indiana, though.

The Marengo Warehouse is an old underground limestone quarry located just a few miles away from Marengo Cave. Opened in the 1800s, it contains almost four million square feet of storage space (more than 100 acres), about a quarter of which is in use. The owners converted it from a mine to a storage warehouse in response to competition from much larger limestone quarries.

All sorts of rumors swirl around the warehouse. For example, the Center for Disease Control supposedly stored supplies there for a long time, but the only actual government property inside are some 10 million MREs. The other contents of the warehouse include 400,000 tires and some 23 million pounds of frozen fruit, most of which are intended for use in yogurt.

The Marengo Warehouse is nowhere near unique. All around the world, we’ve converted limestone mines into storage spaces and business parks. This depends on how we mine the limestone. Since the 1950s, miners have worked carefully to ensure that the leftover space is actually useful, carefully removing 12-foot thick chunks of stone in grid-shaped patterns. When mining is completed, very little construction is needed to ready a cave for other purposes.

The underground limestone quarries are extremely stable. Limestone is made of compressed, ancient, tiny seashells. It's three times stronger than concrete, and has been used in construction for more than three thousand years.

Me…in my man cave.

Of course, there are certain concerns with use of the quarries. Ventilation is a much greater concern than in other mines, so electric forklifts are generally required instead of those powered by propane powered. And, while the older quarries are generally extremely stable, the geological strata above and below the facility must be monitored, to watch for shifting or cracking rock layers.

Now, I’m way too hopeful a man to get all bothered by doomsday scenarios, but if you really want to start preparing for all possibilities, those limestone caves might one day save the human race. I’ll stick to my man cave…when Maggie lets me, of course.

_________

Quotable

Oh, Yard Ramp Guy, just me here, staying on topic with my quotations:

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

— Joseph Campbell

The Fire Next Time

Only You Can Question a Talking Bear

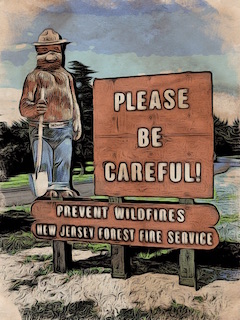

Smokey the Bear causes forest fires. Well, he sort of makes them worse.

I'm only half joking here. In the early 1900s, forest fire prevention and firefighting policies specifically campaigned to suppress all fires and we got very, very good at it.

Smokey the Bear, introduced in 1944, was an effective part of the campaign. The problem with all of the fire fighting, though? Undergrowth started to build up.

As it turns out, ecosystems have actually evolved to deal with fires. For example, many trees actually require fire in order to sprout their seeds. Which means that we “need” regular forest fires in order to clear out undergrowth, so that new growth can fill in.

If that undergrowth isn't cleared out—say, due to people preventing forest fires for decades—when a fire finally does occur, it's likely to be a full crown fire, instead of a relatively harmless and beneficial ground fire. A crown fire is one that grows large enough to burn material up in the tops of trees and completely wipes out all vegetation in a region.

This can lead to massive surface erosion, wildlife die-offs, alteration of surface chemistry, and many other negative consequences. Some crown fires can grow large enough to become firestorms, which create their own wind systems.

Here's a crown fire:

For comparison, here are the aftereffects of a ground fire, in time lapse:

Since the 1960s, though, scientists have recognized and begun pushing steps to correct the problem. Controlled burns have become much more common in the decades since, and the expenses involved in running them safely are more than recouped by the lack of damages from much larger, more dangerous fires.

So, Smokey the Bear did develop from a wrong-minded way of looking at wildfire control, but he still does serve one important purpose: controlled burns need to be started by professionals. If you're camping in the woods, be careful with your fires.

_________

Quotable

Oh, Yard Ramp Guy, only you can prevent bad quotations:

“The grass is always greener around the fire hydrant.”

— Jeff Rich