Or: Statistics, with Commentary

Fun with numbers & patterns

How did the statistician die on his camping trip? He tried fording a river that was three feet deep on average.

I suspect most of us know that statistics can be misleading, but they're still one of the most important tools we have for understanding the world around us. Just ask any baseball fan. Or meteorologist. Or political analyst. (Actually, maybe not political analysts. Best to just slowly back away and not make eye contact with them.)

One of the biggest problems with statistical data actually comes from one of our greatest strengths: our pattern recognition ability. No computer in the world comes close to our ability to spot patterns, but sometimes that very ability backfires on us.

We often start looking for patterns in the data that aren't actually there. An absurd example is the correlation between pirates and global warming—as the number of pirates goes down, global temperatures go up. Sports superstitions are another good example: my favorite team won when I wore my lucky hat, so they'll lose if I don't wear it while they're playing.

Even if you entirely avoid the false pattern recognition pitfall, you still have a lot to consider.

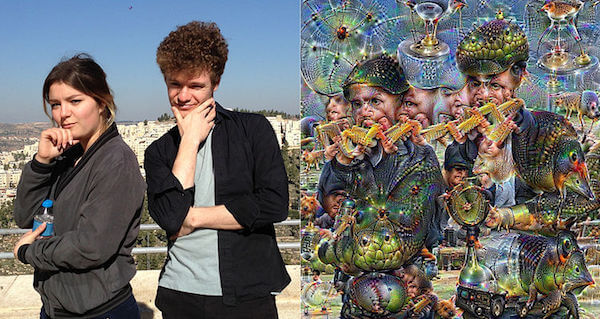

McCoy: Searching for Patterns

Humans also tend to remember the negative more often than not: when the weatherman's wrong, you remember that better than all the (many more) times he’s been right. Commercial weather channels often artificially inflate low chances of rain—say, from 5-10% up to 20%—so that if it doesn't rain it seems like a nice bonus. And if it does rain, well, 20% isn't nearly as low risk as 5%. We like it when errors fall in our favor.

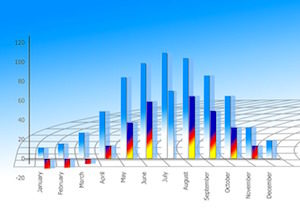

So you're keeping your eyes open for suspect statistics. Great. Now you just have to keep on the lookout for the possibility that the people presenting the statistics are deliberately misleading you. Assuming they haven't just made up the data entirely (less common than you'd expect, since it's so easy to mislead with real data), you've still got to worry about them changing the scale of one of the axes of a graph, switching the axis themselves, or using one of a thousand different tricks within the math behind the data.

A quick example of another trick people can play with data: I recently saw a chart that was supposed to show Victorian England as a safer place to live than the modern day by comparing crimes per capita.

The problem with that? Society's definition of a crime. Crimes that we legislate against and prosecute tend to change over time. We currently have more laws today than at any other point in our history, so it's not surprising that we have more criminal charges per capita. In my example, what historians and criminologists actually use for comparison is murders per capita, because that's always a crime. By that metric, we're a lot safer than Victorian England. (Among other things, muggers today are less fond of garroting their victims.)

It's easy to play tricks like this—using categories of data that seem comparable but really aren't.

How can you look out for statistical shenanigans, if they're so easy to pull off? First, and easiest, try to stick with reliable, well known publications with solid reputations. (Of course, if you're far to one side or the other on the political spectrum, you're probably convinced they're a tool of the other side.)

Second, and much more difficult: Educate yourself. Learn to read data in a discerning matter and familiarize yourself with the subject matter. A good book to start with is Nate Silver's The Signal and the Noise.

Of course, you could just look for data and news sources that agree with what you already think. Confirmation bias is fun!

_________

I kid a lot with my pal Jeff at The Yard Ramp Guy. And now, also this: I'm seriously proud of my friends and colleagues at that fine company on their receiving the Blue Star award from Bluff Manufacturing, which has recognized them as a Gold Dealer of Excellence. Absolutely fitting, and absolutely right.

_________

Quotable

Okay, enough mush. Dear Yard Ramp Guy, statistically I stay quotable each week more than you (but who’s counting?).

“There are lies, damned lies, and statistics."

— Mark Twain

Some science results in vital, society-altering work. Think about our creating vaccines, researching earthquakes, and discovering new construction materials.

Some science results in vital, society-altering work. Think about our creating vaccines, researching earthquakes, and discovering new construction materials. Realizing that if you attach a weighted stick to the rear end of a chicken, it then walks in the same way that dinosaurs were thought to have walked.

Realizing that if you attach a weighted stick to the rear end of a chicken, it then walks in the same way that dinosaurs were thought to have walked. The absurd science category sometimes becomes relevant: Sir Andre Geim won both the Ig Nobel Prize (he was the one to levitate the small frog with magnets) and the Nobel Prize for his work on graphene.

The absurd science category sometimes becomes relevant: Sir Andre Geim won both the Ig Nobel Prize (he was the one to levitate the small frog with magnets) and the Nobel Prize for his work on graphene. If you answered Copernicus or Galileo, you're off by a millennia or two. The Ancient Greeks actually discovered this.

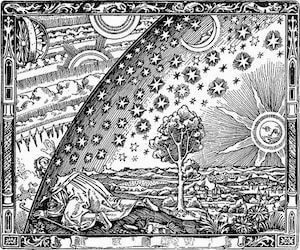

If you answered Copernicus or Galileo, you're off by a millennia or two. The Ancient Greeks actually discovered this. In fact, we can trace the popularization of the idea that people thought the Earth was flat back to specific historians in the 1800s.

In fact, we can trace the popularization of the idea that people thought the Earth was flat back to specific historians in the 1800s. Why do some molded plastic objects have molded plastic screw heads in them?

Why do some molded plastic objects have molded plastic screw heads in them? The most prevalent digital skeuomorph is probably the shutter-click that camera phones and digital cameras make when you take a photo. In film cameras, the sound was caused by a physical function. In digital devices, the sound exists solely to let you know the photo was taken in digital ones.

The most prevalent digital skeuomorph is probably the shutter-click that camera phones and digital cameras make when you take a photo. In film cameras, the sound was caused by a physical function. In digital devices, the sound exists solely to let you know the photo was taken in digital ones.