Dust Busting in Space

For all of the billions of dollars spent getting to the moon, and with all of the challenges NASA had to overcome getting there, one of the most aggravating problems didn't crop up until astronauts had already landed: moon dust.

For all of the billions of dollars spent getting to the moon, and with all of the challenges NASA had to overcome getting there, one of the most aggravating problems didn't crop up until astronauts had already landed: moon dust.

Moon dust has a perfect storm of properties that’s an absolute nightmare to deal with. It's extremely fine grained, yet simultaneously abrasive, like someone ground up bits of sandpaper. The best way to think of moon dust is like powdered glass. It also has severe static cling, thanks to the solar wind continuously bombarding it, so it sticks to every bit of equipment—suits, lenses, you name it. Moon dust also gums up spacesuit joints, wears through layers, and gets all over habitats.

Part of the reason the stuff is so difficult to deal with is that it’s formed by meteor and micrometeoroid bombardments, unlike earth dust. Since there is no wind or water to erode the dust, it stays just as sharp as the day it was shattered off.

Moon dust even causes its own health condition, known as lunar hay fever, causing severe congestion and other problems. Long-term exposure to the dust could likely cause health problems very similar to silicosis.

That's not to say NASA hasn't been researching solutions for dealing with all that moon dust. Each grain contains a small fragment of metallic iron, which means that we can collect it with a magnet. The grains also melt quickly and easily with a microwave. One scientist even envisions placing microwaves on the front of lunar rovers, so that our astronauts could create “roads” as they travel.

The Moon hardly has a monopoly on dusty conditions. The dust on Mars is believed to be such a strong oxidizer that it can burn your skin, much like lye or bleach. Martian dust on your skin would leave burn marks.

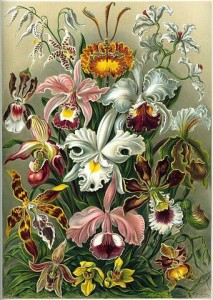

I like to keep a lot of houseplants around—it really helps make a house feel like a home.

I like to keep a lot of houseplants around—it really helps make a house feel like a home. Eventually, the extreme demand resulted in rare and delicate orchid species being driven extinct in the wild, all over the world.

Eventually, the extreme demand resulted in rare and delicate orchid species being driven extinct in the wild, all over the world. Photo by Arshiya Urveeja Bose [

Photo by Arshiya Urveeja Bose [ The most famous of the bridges, the Umshiang Double-Decker Root Bridge, is actually two of those bridges, with one stacked directly over the other. Local dedication to the art has kept the bridges alive and prevented them from being replaced with steel. (Steel, frankly—and with all respect to those dealing with, ahem,

The most famous of the bridges, the Umshiang Double-Decker Root Bridge, is actually two of those bridges, with one stacked directly over the other. Local dedication to the art has kept the bridges alive and prevented them from being replaced with steel. (Steel, frankly—and with all respect to those dealing with, ahem,