In Uzbekistan No One Can Hear Fish Scream

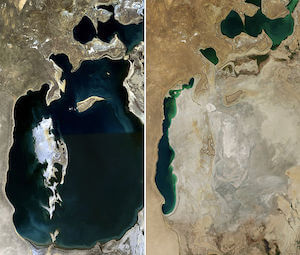

The Aral Sea: 1989 (l) and 2014 (r).

In the early 1960s, the Aral Sea—in between today's Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan—was one of the four largest lakes on the planet. By 2007, it had reduced to ten percent of its former size.

The Aral Sea's name roughly translates to “The Sea of Islands,” a reference to, shockingly enough, its many islands. It played a vital part in the region's history, economy, and culture, as well as feeding much of the region with rich fisheries. And then, in the early 60s that started to change.

The Soviet Union began a series of projects in the region. The largest of these was the diversion of the two main rivers that fed the Aral Sea, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, for the purposes of agricultural irrigation.

The USSR planned to use the water to turn the region into one of the world's largest cotton exporters, and this actually worked, for a little while. As many of the irrigation canals were poorly constructed, they often lost as much as 75% of the water flowing through them.

And so the Aral Sea began a slow but steady decline in water level. The rate of evaporation increased as more and more water was taken from the rivers for irrigation purposes. The Soviet Union was aware that the lake would disappear. They simply weren’t concerned. As more water evaporated and wasn't replaced, the salinity of the lake steadily increased, by almost 500%.

By 2007, at ten percent of its normal size and split now into two lakes, the North and South Aral, it had a salinity almost three times that of the ocean, killing almost all its natural life. (Though it still wasn't as salty as the Dead Sea.)

The huge plains left as a result of the sea evaporation are coated with salt and toxic chemicals (weapons tests, industry, and agricultural runoff.) These nasty sediments are picked up by the wind and carried great distances, causing cancer and other ailments all over the region. There's so much of the toxic dust that the region now regularly has poisonous dust storms.

Some conservation efforts have slowed the evaporation of the sea. Engineers have begun to repair and strengthen the irrigation canals in order to minimize the losses through them. The northern half, in Kazakhstan, has been dammed off from the southern half, resulting in a rise in sea level in the northern half, with salinity levels dropped to the point where life can survive there again.

There's little hope for the southern half. Uzbekistan has no interest in reducing its irrigation demands, or efficiency, and has instead begun working on exploiting the exposed seabed for oil.

_________

Quotable

Okay, Yard Ramp Guy — S-omething to quote (in case yours isn’t quotable):

“Sadness is but a wall between two gardens.”