Only You Can Question a Talking Bear

Smokey the Bear causes forest fires. Well, he sort of makes them worse.

I'm only half joking here. In the early 1900s, forest fire prevention and firefighting policies specifically campaigned to suppress all fires and we got very, very good at it.

Smokey the Bear, introduced in 1944, was an effective part of the campaign. The problem with all of the fire fighting, though? Undergrowth started to build up.

As it turns out, ecosystems have actually evolved to deal with fires. For example, many trees actually require fire in order to sprout their seeds. Which means that we “need” regular forest fires in order to clear out undergrowth, so that new growth can fill in.

If that undergrowth isn't cleared out—say, due to people preventing forest fires for decades—when a fire finally does occur, it's likely to be a full crown fire, instead of a relatively harmless and beneficial ground fire. A crown fire is one that grows large enough to burn material up in the tops of trees and completely wipes out all vegetation in a region.

This can lead to massive surface erosion, wildlife die-offs, alteration of surface chemistry, and many other negative consequences. Some crown fires can grow large enough to become firestorms, which create their own wind systems.

Here's a crown fire:

For comparison, here are the aftereffects of a ground fire, in time lapse:

Since the 1960s, though, scientists have recognized and begun pushing steps to correct the problem. Controlled burns have become much more common in the decades since, and the expenses involved in running them safely are more than recouped by the lack of damages from much larger, more dangerous fires.

So, Smokey the Bear did develop from a wrong-minded way of looking at wildfire control, but he still does serve one important purpose: controlled burns need to be started by professionals. If you're camping in the woods, be careful with your fires.

_________

Quotable

Oh, Yard Ramp Guy, only you can prevent bad quotations:

“The grass is always greener around the fire hydrant.”

— Jeff Rich

There's actually a name for this: The

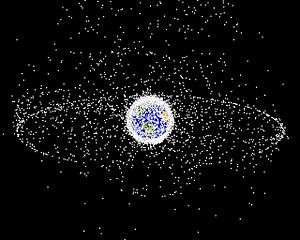

There's actually a name for this: The My family goes to a lot of movies. We're not film buffs, by any means. Usually, we're looking for snappy dialogue and explosions. A couple years ago, we saw the film “Gravity.” For those who haven't seen it, a runaway debris cloud destroys satellites and space stations. Even though the science in that movie was pretty badly off, in a lot of ways, something like it does have the potential to occur.

My family goes to a lot of movies. We're not film buffs, by any means. Usually, we're looking for snappy dialogue and explosions. A couple years ago, we saw the film “Gravity.” For those who haven't seen it, a runaway debris cloud destroys satellites and space stations. Even though the science in that movie was pretty badly off, in a lot of ways, something like it does have the potential to occur. A Kessler cascade could potentially make

A Kessler cascade could potentially make