Many inventions seem to arrive out of order. That is: considerably ahead of or behind where you’d expect them to show up. One of the best examples of this is the semaphore.

Early Semaphore

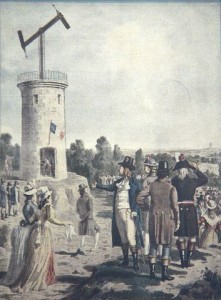

The semaphore was a long distance communication system invented in 1792 by the Frenchman Claude Chappe. It takes the form of a series of towers with clear lines of sight between them, with large pivoting arms on top. The arms are moved in a visual code, representing the individual letters, which the next tower in the line then repeats, and so on and so forth.

When it was invented, the semaphore was the fastest method of communication available at the time. There were quite a few limitations, of course: it didn’t work well (or really at all) at night or in bad weather, the towers were expensive to build, several were destroyed by angry mobs, and it required attendants at every tower, which drastically increased operating costs.

You could still send messages faster through the semaphore than by other method, and it saw considerable use for the next 50 years, until the electrical telegraph took its place.

It seems like the semaphore should have been invented much, much earlier. None of the technology was by any means too advanced for, say, the Roman Empire. It’s just swinging arms on a tower, after all, and they had plenty of gears and pulleys and the resources to develop a massive network of them, if they so chose. They had the math necessary to develop codes. There were even a number of Roman experiments in optical telegraphy. So why didn’t they build the semaphore?

The answer is actually pretty simple: telescopes. The Romans lacked the advanced optics necessary to build decent telescopes, which meant that semaphores would’ve been built much, much closer together, to the point where they would no longer be cost effective, even for the mighty Roman Empire.

Technological advancement isn’t conducted in a vacuum. Each new invention requires a network of other advances around it, making new tools, ideas, and techniques available to the inventors. This is not to say there’s a set order in which technology must be invented. Many of our technologies were not an inevitable development but, often, merely choices made for business or cultural reasons, or even out of convenience.

Our technology could have ended up radically different than it did…but it still would have built itself from the ground up.