The Yard Ramp Guy for Troubled Times

My friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, is honest as the day is long. He's also humble, which means ⏤ beyond the necessary marketing campaigns to keep competitive in the industry ⏤ he might not readily draw attention to himself or his business.

I, McCoy Fields, am not so humble. That's why I'm proud to share with you just a bit of what Jeff and his team are doing in response to the coronavirus pandemic that has so quickly altered our landscapes and disrupted our world.

Ramping Up in Troubled Times

There's a difference between what we can see and what we can't. COVID-19 is invisible to the naked eye, an insidious, lethal virus that does not discriminate, that transmits from person to person through proximity, breath, and touch. It's a frightening thing with all-too-often devastating results. A yard ramp is a tangible three tons of steel: an incline with purpose and utility.

The clamping off of much of the country to limit transmission of coronavirus is having devastating effects. The alternative is worse. Essential businesses continue to operate. That's why the supply chain keeps our grocery stores stocked. And that's why The Yard Ramp Guy continues to sell and rent its inventory.

Yard ramps classify as essential tools to emergency service and product providers combatting the pandemic. The Yard Ramp Guy has placed ramps at Coronavirus Emergency Distribution staging sites and rented a ramp to a hospital in New York City ⏤ sadly, to provide access to refrigeration trucks serving as temporary morgues. I've known more life-affirming examples. Yet this is important and, yes, essential.

The Yard Ramp Guy is listed in ThomasNet's COVID-19 Response Suppliers.

In good times and bad, Jeff's yard ramps are workhorses, functioning without complaint to help movement between points.

I've never been prouder of my friend Jeff and his team.

Stay safe and be well.

Archives: The Incan Terraces

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so: my From the Archives series. This week: Terraces⏤the opposite of ramps?

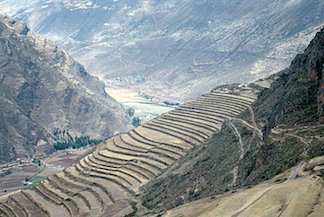

The Inca are surely one of my favorite ancient cultures. Much of this is due to the unusual amount of research available on their building techniques and architecture. The pieces of their engineering I've been reading about lately are their terraces.

Terraces might be something of an opposite of ramps, but that just makes them more fascinating. Living among some of the steepest mountains in the world, the Incans had to improvise heavily when it came to all sorts of facets of their life. Their terraces did a lot more than provide flat areas for food production (though don't get me wrong: that was just a little bit important); they also helped to control erosion and landslides.

In fact, much of Incan architecture was built to be earthquake resistant, and the terraces were no exception. They were so well built that, despite the Incan's comparatively low technological level, their terraces survived from Pizarro's conquest of their empire, totally forgotten, all the way up to the twentieth century, when they were rediscovered.

Do you think anything we build today would last that long without maintenance? Not likely. This workmanship stretched all the way through their construction, too.

The Incans by no means had a monopoly on agricultural terraces, of course. Terrace farming has arisen independently in dozens of cultures worldwide, with almost as many individual styles. It's almost certainly the most efficient method of farming in the mountains.

The most famous are almost certainly the rice terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras: they've actually been declared a UNESCO heritage site. You've almost certainly seen images of them before. They've been farmed continuously for something like 2000 years, which is absolutely crazy. That's not just architecture, it's a way of life.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: The Power of Powder

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy writes his own cautionary tale of sorts: some seemingly sci-fi tale of producing a yard ramp with a 3-D printer.

Click HERE to read all about it.

Archives • Switchbacks: Ramp Diversity

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so: my From the Archives series. This week: Italy makes me dizzy.

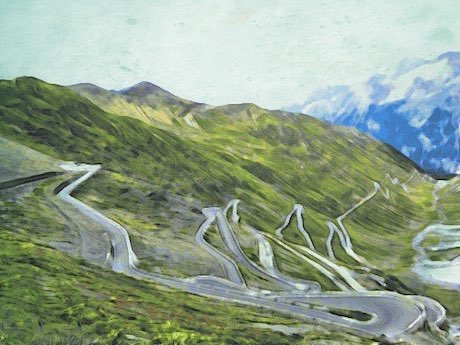

There is one kind of ramp I absolutely love, except when I'm using it, in which case I absolutely hate it. That ramp is the switchback.

Anyone who's done much mountain driving learns to hate switchbacks, even though they're some of the most cost-effective engineering tricks we have in the mountains. (Much, much cheaper than tunnels, that's for sure.) Truckers especially hate them. I've known some who will go hours out of their way to avoid them. I think gearheads are the only ones who enjoy them.

Careful, there.

One of the craziest examples of the breed is the Stelvio Pass in Italy. It's one of the highest roads in the Alps and has 75 switchbacks. Seventy-five! Not a road you want to drive fast on, or even drive on at all if you can help it. Apparently, it’s so dangerous during the winter and spring that they close it completely during those seasons.

Of course, being dangerous, gearheads flock to it. That British car show everyone likes, “Top Gear” (I don't watch that show anymore after what they said about the F150), declared it the greatest driving road in the world. (Or at least in Europe. Have you seen the pictures of the crazy roads they have in the mountains in India?)

The Italian bicycle Grand Tour frequently goes through Stelvio Pass. (The Giro d'Italia, sister race to the Tour de France. I try to catch all three of the Grand Tours when I can.) Thousands and thousands of cyclists ride through Stelvio Pass every year.

It's easier to find info on battles fought at the pass than it is to find anything beyond basic info on its construction or maintenance, but that's pretty constant. Historians are obsessed with wars, despite the fact that construction and architecture affect us way more.

I'm working on persuading Maggie on this European vacation bit but, as carsick as she gets, I don't think that Stelvio Pass will be on the itinerary.

The Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Moving Your Yard Ramp

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy provides some astounding weight comparisons (and gives me newfound respect for the blue whale, from which I'll never ever wish to receive a tongue lashing), then transitions from heavy to smooth and shows how easy it is to move a yard ramp.

Buckle up, then click HERE to read all about it.

The Greek Ramp Hybrid

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original contributions. And so: my From the Archives series. This week: ancient Greeks multitasked in a most remarkable way.

Most of the historical ramps I research are generally of a pretty temporary nature: pyramid construction ramps, siege ramps, etc. They're built for a single purpose and then abandoned or destroyed. They're machines, and they don't have a long-term purpose.

I have found a few ramps that are different, though, and one of my favorites is the Diolkos.

The Diolkos, built by the ancient Greeks, was half ramp, half causeway. It was used to transport ships across the Ithmus of Corinth, saving them a dangerous sea voyage. The ancient Greeks actually dragged the ships overland on it. (You'd think a canal would be easier to use, but canals are a lot harder to build and maintain.) Huge teams of men and oxen would have pulled the boats and cargo across it in about three hours per trip.

The Diolkos, built by the ancient Greeks, was half ramp, half causeway. It was used to transport ships across the Ithmus of Corinth, saving them a dangerous sea voyage. The ancient Greeks actually dragged the ships overland on it. (You'd think a canal would be easier to use, but canals are a lot harder to build and maintain.) Huge teams of men and oxen would have pulled the boats and cargo across it in about three hours per trip.

No one is quite sure when the thing was built, but at best estimate it was in use from 600 BC to 100 AD, which is a pretty good lifespan for a project like that. It was mostly used for shipping but also served a pretty vital role for navies during war.

There isn't nearly as much information on the Diolkos as I would like out there. The ancient Greeks mostly wrote about their gods and heroes and wars and such, which is disappointing but not unexpected. Most people want entertainment; they're not looking to find out how the world works.

Today the site has been destroyed in parts by the Corinth Canal, and much of the excavated portions are falling apart due to lack of maintenance and boat traffic on the Canal. It's not exactly the Parthenon, but it represents a vital look at how the day-to-day functioning of an ancient society actually worked.

Maybe I can convince Maggie that we should go to Greece next vacation.

The Yard Ramp Guy: Ramps Rusting Gracefully

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy pivots from writing about steel as the literal foundation of his business to take on the benefits and drawbacks of new technology. Of course, I always appreciate a cautionary tale.

Click HERE to explore how he goes from ramps to rusty sidewalks.