Cold Welding

Or: One Advantage of Being Messy

Shut the door, please.

On June 3, 1965, a door failed to close.

In most situations, this would be a minor annoyance, but this was in the middle of the Gemini 4 space mission, and the door in question was the outer airlock door of the capsule—while they were in space.

So, yes: this was rather a big problem. In the end, the problem turned out merely to be a jammed spring; they managed to get the door shut. There were serious concerns, however, that a more severe problem might have occurred: cold welding.

Cold welding is exactly what it sounds like: Two pieces of metal welding together in cold conditions, rather than through application of heat. Specifically, it involves two clean, flat pieces of metal bonding together when they contact in a vacuum.

These need to be two exceptionally clean pieces of metal, since any contaminants can interfere with the process. Once they're welded, however, as far as the two pieces of metal are concerned, they're just one piece, not two. The process actually bonds the two together as if they'd always been one piece.

Needless to say, this is a big concern in space, where you really can't afford to have random mechanical failures due to pieces deciding they don't want to move.

Quite a few satellites have been lost through cold welding over the years, and the Galileo probe sent to Jupiter had its high-power antenna welded shut in this way.

There are a few good methods to help prevent cold welding these days—using plastic, ceramics, and coatings whenever possible, as well as making sure that any metals in or near contact with one another are different metals, to reduce risks of cold welding.

Finally, we have one more thing protecting us: our natural messiness. Skin oil, dust, and other contaminants can help prevent cold welding. And, guess what? We're really good at getting all that stuff on everything, even our super-expensive, high-tech space probes. Three cheers for being messy.

Discovering the Turkish Underground

Or: Tuff Luck

The Turkish Underground

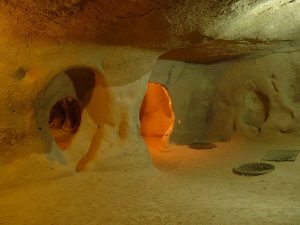

The Cappadocia region of Anatolia, Turkey, is riddled with underground cities. In 1963, a man in the region knocked down a wall of his home (for home renovations, I hope, though maybe he was just in a particularly bad mood) and discovered a mysterious room built into the rock.

After a little more digging, he broke into a whole intricate tunnel system: the Derinkuyu underground city, carved thousands of years ago.

The Cappadocia region sits on a one kilometer (3,300-foot) tall volcanic plateau. Millions of years ago, it was covered in volcanic ash, which solidified into tuff, a type of volcanic rock.

That made for easy digging, and the inhabitants of the region some 3,000 years ago quickly took advantage of this to dig their elaborate tunnel cities. (Not all tuffs are soft and easily dug into, however; some tuffs are extremely tough.)

People developed a wide range of uses within the tunnel systems. Food storage was one of the earliest and most reliable: cave systems tend to maintain constant temperatures, often considerably cooler than the surface.

We’ve also used underground cities multiple times throughout history to hide from attack. Derinkuyu is extensive enough that it could have hidden as many as 20,000 people. They had the benefit of ample storage space, which included wine and oil presses, stables, refectories, and chapels.

The city contains five different levels, each of which could be closed off independently of the others. Not least incredibly, the Derinkuyu is also connected to the Kaymakli underground city by an 8 km (5 mile) underground tunnel.

There is some debate about who first built the cities. Some attribute them to the Hittites (between the 15th and 12th centuries BC), but most believe they were constructed by the Phrygians (between the 8th and 7th century BC), the people who supplanted the Hittites, and then themselves faded away during Roman times.

The Derinkuyu was used by the Byzantines much later to defend themselves during the Arab Byzantine wars (780-1180 AD). Even as late as the early 20th century, the tunnels were still in use by the locals to avoid Ottoman persecution, only falling into disuse in 1923. So, doing our math, the lost city had only been lost for 40 years when it was re-found.

Today, much of the Derinkuyu underground city is open for visitation by tourists. And more than 200 other underground cities with a minimum of two levels (40 have three or more) have been discovered in the region.

Modern Problems: Balinese Rice

Meet the New Boss, Not as Good as the Old Boss

Sometimes . . . The Rice Rules

There’s a long list of stories in history where Europeans tried, and miserably failed, to apply European farming techniques to other places around the world.

It turns out that you need to adapt your techniques to your environment, not the other way around. The Ancient Greeks had a relevant term: metis, or local knowledge. It’s important to know how things work where you live.

One of the most interesting European agricultural failures occurred in Bali. The Balinese had, over millennia, developed incredibly complex rice farming techniques. Rice is absolutely central to Balinese Hinduism and cuisine. Rice is so important that the Bali word for rice, nasi, means “food.”

Incredibly complex water terraces cover Bali, running up and down hillsides, with equally complex irrigation systems all over the place. They have farming cooperatives known as subaks that consist of every farmer sharing a water source. Everything is orchestrated by the intricate and complicated calendar known as the tika. And, thanks to all of that, Bali was able to maintain an immense population density.

Yours truly, about to order a rice dish.

Then the Europeans came along, decided all of these old methods were nonsense, and decided to replace them with more modern techniques. They failed to significantly change anything.

After Indonesia gained independence, the Indonesians, in an effort to modernize, began applying those same European techniques in Bali. The water districts quickly fell into mismanagement: the new rice strains they’d introduced were more vulnerable to pests, and uniform rice crops were more vulnerable to disease, etc., etc.

In the 1980s, scientists began actually modeling the differences between the old and new systems and realized exactly how brilliantly adapted the old systems had been to Bali’s climate and ecosystem. Today, Bali has slowly reintroduced modified versions of the old system back in place. They’re not bringing back the old rice strains, but they’re reworking things to run off the tika calendar again.

It pays to understand your environment. The real world always beats theories.

Crowdsourced Explorer

Or: Privatizing the Cosmos?

"Crowdsource me up, Scotty."

On August 12, 1978, the International Cometary Explorer (ICE) was launched into space on a heliocentric (sun-centered) orbit.

Originally launched as the International Sun/Earth Explorer 3, NASA intended ICE to investigate the solar wind and Earth's magnetic field. The unmanned probe finished that mission successfully and was then repurposed into being the first spacecraft to visit a comet. It was also the first spacecraft to maintain an orbit at the L1 Lagrange point.

So, ICE/ISEE-3 was a pretty big deal, NASA reluctantly cut contact in 1997. They made brief contact with it in 1999, just to check that it was still there. In 2008, as it happened, the probe was not only still there; the thing was still functioning. Then, in 2014, as ICE approached Earth again, NASA determined that the probe continued to function…and maybe it was possible to bring it back into operation.

NASA toyed with the idea briefly, but they ended up doing nothing (yes, it’s always easier to do nothing).

Then a remarkable thing happened: a group of interested scientists, engineers, and programmers began a grassroots attempt to bring the satellite back to life. With NASA's blessing and some assistance, they began their campaign to revive the probe.

They crowd-funded their expenses and actually began to acquire all the defunct, obsolete hardware they'd need reanimate the probe. On May 29th, the team successfully made contact with the probe.

Though they were able to fire the thrusters one time, mechanical issues prevented them from doing so again due to the loss of the nitrogen gas pressurizing the fuel tanks. They eventually lost contact on September 16th.

It seems unlikely that they'll ever regain contact. Yet this was an incredible milestone: theirs was the first crowd-sourced, crowd-funded, citizen-driven planetary space mission.

That's one heck of an achievement.