The Monongahela-Duquesne Connection

Fun with Funiculars

It's a Steep Slope, Sherlock

It's been a while since I've written about one of my favorite subjects. And since this started out as a blog all about ramps, it feels about time to ramp up once again.

First, a refresher course on the funicular. It’s a railway on a steep incline—often 45 degrees or more—that contain a pair of cars that are attached with a cable and that counterbalance one another. When one car moves up, the other moves down. I've written about them before (see HERE). I think they're fairly extraordinary.

End of refresher course.

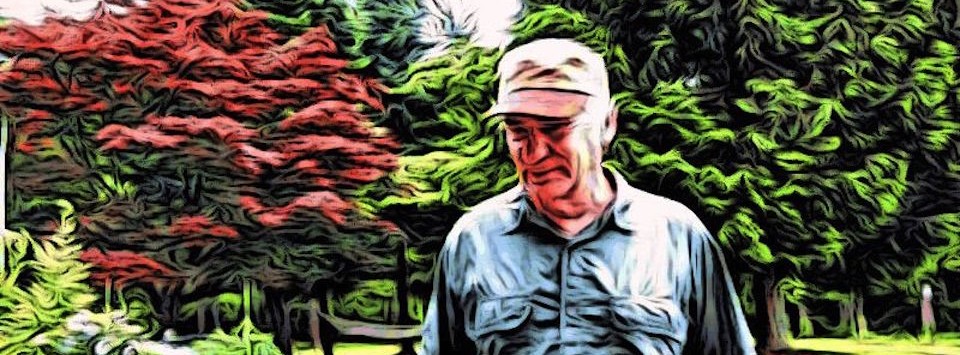

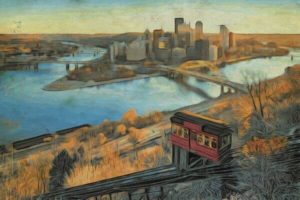

The Monongahela Incline is America's oldest continually operating funicular. Located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, it stretches from the flood plain of the Monongahela River up to the top of Mount Washington, a neighborhood with one of the most beautiful views in any city in America. (When the funicular was built in 1870, however, the neighborhood was known as Coal Hill.)

Around 1860, Pittsburgh's expanding industrial base began drawing German immigrants (among others) to the area. Since the industrial districts already filled up most of the flood plain, the new workers began settling on the hillsides nearby.

With few good roads and little public transit, the trek to and from work was up and down the steep and frequently muddy hill. Germany, however, had employed funiculars for some time already, so residents quickly proposed the opening of their own funicular.

A second funicular reaching the neighborhood, the Duquesne Incline, opened in 1877. Originally a cargo carrier, engineers later converted it for passenger use.

The Duquesne Incline remains open today, except for a one-year closure in the 1960s, when it was saved by a community fundraiser.

Other funiculars have been built, but only the Monongahela and Duquesne Inclines made it out of the 1960s…along with some people I know.

_________

Quotable

Yes, Yard Ramp Guy: I’ve read your comment this week regarding our not meeting at the center of our alphabetical quote-off. According to my calculations (a 1986 Texas Instruments calculator), you and I had a 50 percent chance of landing on the same letter. The problem—and the beauty—here is that we’re both of us consistent. Alas, we’re like two ships that pass in the night. Not to quote Manilow, or anything.

“Management: An activity or art where those who have not yet succeeded and those who have proved unsuccessful are led by those who have not yet failed.”

— Paulson Frenckner

Bretzian Geology

A Flood of Ideas

J Harlen Bretz, 1949

Geologists have a tendency to get really worked up about flood-related theories. Early in the history of the science, the Biblical flood provided the foundation for most every claim, and we approached all of geology in that context.

Evidence built up over time until it forced the geological community to acknowledge that nothing of the sort had happened. In fact, they went so far as to construct a doctrine called uniformitarianism, which claimed that all past geological processes are the same as the ones operating now.

Then, in 1920, a geologist named J Harlen Bretz developed a new set of flood theory that would shake things up all over again.

Bretz's research and field work led him to propose a series of absolutely catastrophic floods in the Pacific Northwest. I won't go into all the various iterations of the idea over the years, but the floods as we understand them now are far more destructive than almost any other geological events today.

The Cordilleran

During the ice ages, the Cordilleran continental ice sheet dwarfed any glacier existing today. It and its several sibling glaciers around the world held enough ice to lower the sea levels by hundreds of feet. As the temperature gradually increased, however, a massive lake, around the size of one of the Great Lakes, began to melt into the top of the ice sheet, somewhere in Western Montana.

Over time, cracks began to grow in the massive ice dam holding the lake in, until it finally shattered, releasing all the water at once. The floodwaters would have moved between 45 and 60 miles per hour, cresting at over 400 feet tall in the Columbia River Gorge and the Willamette River Valley.

McCoy Fields, 2017

Flood waters carried enormous boulders as though they were twigs, deforming entire landscapes. The debris from the flood flowed hundreds of miles through Idaho and Oregon, and from there well into the Pacific Ocean.

Oh, and there wasn't just a single flood. The ice sheet eventually formed a new lake and the cycle repeated itself as many as forty times. This all took place well before any humans arrived in North America.

The geological establishment resisted Bretz’s ideas for years, but Bretz and his allies eventually won the day in a crushing victory. Decades later, Bretz complained that he no longer had any enemies to gloat over.

_________

Quotable

Yes, Yard Ramp Guy: Now, here’s a quotation:

“Nature gave men two ends -- one to sit on, and one to think with. Ever since then man's success or failure has been dependent on the one he used most.”

— Robert Albert Bloch

Discursive on the Gamburtsev

To Climb These Mountains, You Need to Dive

The Gamburtsev Discursive

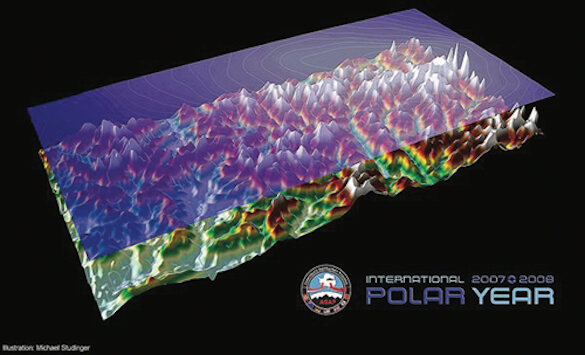

There's a mountain range on Earth that no human has ever seen.

The Gamburtsev Mountain Range is about the size of the European Alps and are as rugged as the Rocky Mountains. Why has no one ever seen the mountain range? Because it's buried underneath 10,800 feet of ice in Antarctica.

Oh, and water flows uphill there.

One of the more interesting aspects of the Gamburtsevs is the ruggedness to them. They're more than a hundred million years old. By now they should have eroded enough to resemble the Appalachians, instead of looking like the Rockies.

Scientists today think the mountain range has actually been preserved by the ice above it—a counter-intuitive result, since absolutely nothing erodes mountains faster than glacial ice in normal circumstances.

The Antarctic ice sheets are so thick, however, that the ice starts to behave in a bizarre manner. As the pressure grows stronger farther and farther down into the ice sheet, the freezing point of water starts to drop lower and lower, until liquid water eventually exists at the bottom; the freezing point of water down there is simply just too low. The pressure actually forces the water to flow uphill!

We've identified other mountain ranges that were presumably buried underneath ice sheets during the Ice Age, including the Torngat Mountains in Canada and the Scandinavian Mountains.

If the ice in Antarctica ever melts, one effect will be that the mountains (currently with an average height of 8,850 feet) would rebound upwards. Ice sheets are so heavy that they actually press the continental crust downward into the mantle.

Removing the Antarctic ice sheets would cause the Gamburtsevs to rebound back up to 10,800 feet in height.

Thankfully, we're not likely to see them any time soon. Even the worst models for global warming don't predict that rebounding scenario as extremely likely. Which is a good thing because it would raise the sea level some 200 feet.

_________

Quotable

Dear Yard Ramp Guy: Oh yes—a quote for you:

“O, what a tangled web we weave; When first we practice to deceive!”

— Sir Walter Scott

Norwegian Gratitude

Seeding the Svalbard Archipelago

Entrance to the Svalbard Vault

These days, we’ve come to expect powerful governments and military forces building bunkers underneath mountains.

For example, China has an underground network of tunnels for ferrying nuclear weapons, and the United States has a vast operations center for NORAD under Cheyenne Mountain.

One of the most secure of all these underground facilities is somewhat surprising, though. The Norwegians built it, and they use it for plants.

They constructed the Svalbard Global Seed Vault to hold a wide variety of plant seeds that are duplicate samples of seeds held in gene banks from around the world.

Its intended purpose is to provide a form of insurance: as a backup should we lose other seed gene banks or if we experience large-scale crises on a regional or global scale.

By request of the Norwegian government, the vault holds no genetically modified seeds. Engineers built the structure 390 feet inside a sandstone mountain on the Svalbard archipelago, an Arctic island chain that is one of the coldest places on the planet.

Svalbard lacks tectonic activity, ensuring the vault is safe from earthquakes. The surrounding permafrost helps keep the vault cool; even if the refrigeration units failed, it would take several weeks for the facility to rise to the surrounding sandstone's temperature, which would remain below freezing. And the bunker is 430 feet above sea level, so even if the ice caps completely melt it won't be flooded.

The vault's primary purpose isn’t to provide new seeds to a region facing a major disaster (though it can do that in a pinch). Instead, Svalbard is there to restock smaller gene banks around the world in case they've been affected by a disaster or have lost seeds to mismanagement.

It's best to think of it as a bank to which other banks can make deposits (those being the world's 1,750 other seed banks).

In fact, they're often called to do so: in 2012, the Philippines lost its entire seedbank to flooding and fire and received assistance from the Norwegian initiative.

_________

Quotable

Oh, Yard Ramp Guy: Please regard my reverse-alphabetical entry this week...

“Plenty of people miss their share of happiness, Not because they never found it, But because they didn't stop to enjoy it.”