From Hunting to Farming

Or: Old Agriculture Courtesy Younger Dryas

Younger Dryas...

I've written a good bit about archaeological sites before, including Göbekli Tepe, one of the oldest sites in existence. And it's not a topic I'm likely to exhaust any time soon. Today, I want to share fascinating info about the oldest agricultural site on the planet.

People lived and worked Tell Abu Hureyra—located in present-day Syria, about 75 miles east of Aleppo, between 13,000 and 9,000 years ago. The epoch shows civilization’s clear transition from hunter-gatherer communities to agricultural communities.

Abu Hureyra was home to the earliest known farmers in history. The Tell part of its name refers to the hill over the site; a tell is a large, flat hill composed of collapsed buildings, debris, and household items that piled up over the years the village existed.

Agricultural activity at the site started at the beginning of the Younger Dryas, which is commonly described as the cause of the rise of agriculture. The Younger Dryas was a brief return to the climate of the Ice Age, 13,000 to 11,000 years ago. (That’s brief…in geological term.)

…and Older McCoy

Many scholars believe this period kick-started agriculture. The rapid and prolonged temperature dip of the Younger Dryas rendered the Middle East less capable of supporting hunter-gatherers, forcing them either to migrate southwards or adopt new strategies for acquiring food. And here we’re talking about agriculture.

Abu Hureyra shows this exact pattern. Most of the hunter-gatherers fled early in the Younger Dryas, with the remainder switching to agriculture. It remained inhabited for another 4,500 years after that.

Sadly, Abu Hureya is no longer accessible to anyone. It was drowned underneath Lake Assad following the construction of the Tabqa Dam in 1974. The site had only been excavated for the two years prior to that. And in great haste: archaeologist knew their time was limited.

_________

Quotable

Okay, Yard Ramp Guy: No complaints from me, but know that my challenge is greater than yours. You try spelling backwards.

“Values are tapes we play on the Walkman of the mind any tune we choose so long as it does not disturb others.”

— Jonathan Sacks

Anabranch This

Or: Dam That Stream

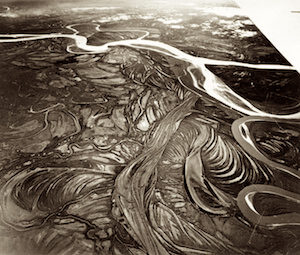

Anabranching: From the Air

If you live on the East Coast, especially in the mid-Atlantic region, you might be familiar with the types of streams you often find there—meandering streams, with high banks full of fine sediment. They tend to erode badly, so stream restoration has become a multi-billion-dollar industry on the East Coast.

Here's the interesting bit: those high-banked streams they're restoring aren't natural.

Prior to European settlement, streams on the East Coast tended to be composed of multiple channels that were divided by islands and wetlands, with fairly low banks (also called anabranching). The wetlands tended to be highly effective carbon sinks. You definitely didn't find the single-channeled meandering streams you do today. So what happened?

In a word? Millponds. Water-powered mills dammed up rivers and streams all across the East Coast. This slowed down the streams and created spots where the sediment could settle out of the water at much greater rates than normal, producing those high stream banks.

A Millpond

Now that we don't use water-powered mills to grind our flour and cut our lumber like we used to, most of those mills have vanished over time. And most of that multi-billion- dollar stream restoration industry? It's just trying to keep the streams and rivers flowing in a manner unnatural to them.

The stream restoration industry players aren't fighting an entirely uphill battle. Some of them are starting to listen to the science. Instead of repairing the eroding streambanks, they're accelerating the process in order to return the streams to their former state.

This approach is not exactly popular yet because it involves bulldozing all the plants and trees that have grown on the stream banks, which isn't very pretty.

There's a more important lesson to take from all this: namely, that we change the world around us in ways we seldom recognize.

Many of our ideas about what nature is come from what we see around us, which is seldom untouched. And nature possesses nearly unstoppable inertia; look at the stream banks eroding now.

Nature had to wait centuries, but she’s still reclaiming her streams on the East Coast. We need to be cautious about where we build and how we alter nature. It’s best to work with her. In the long run, working against nature is seldom a winning strategy.

_________

Quotable

Yep, Yard Ramp Guy: Backwards we continue with the alphabet quote-off:

“Waiting for perfect is never as smart as making progress.”

— Seth Godin

The Curious Coral Castle

Ed, the Latvian-American Eccentric

28 Years in the Making

Eccentrics building bizarre monuments is somewhat old hat, but Edward Leedskalnin took it a little farther than most.

The Coral Castle, located in Southern Florida, is a bizarre complex of limestone megaliths. Each stone weighs several tons.

Leedskalnin spent more than 28 years building the coral castle, and he allowed no one to watch him work. He claimed that the only tool he used was a “perpetual motion holder,” whatever that is.

His eccentricities don't stop there. He claimed that magnets cured him of tuberculosis. When asked how he built the castle, he would only answer, “It's not difficult if you know how.”

The “castle” itself is constructed of a thousand tons of oolitic limestone, which comes from coral. The joints of the stones use no mortar; all of the structures are held together by their weight alone. The whole thing is surrounded by a wall of eight-foot tall standing stones, which Hurricane Andrew didn’t even shift in 1992.

Leedskalnin himself lived in a two-story tower near the center of the maze. Other structures on the site include a sundial, fountains, obelisks, and countless pieces of stone furniture. The largest stone weighs 27 tons, and the largest monoliths top 25 feet.

Coral Castle’s most famous structure is the revolving gate: an eight-ton structure that a child could push open with a finger. The gate had to be removed for repairs in the 80s, when it was discovered that Leedskalnin had drilled a hole through the middle and put a metal shaft connected to a truck bearing through it. The repaired gate, unfortunately, doesn't open quite as easily.

Edward Leedskalnin once claimed that he had discovered the secrets of the pyramids. This actually might not be too far off. Archaeologists and engineers have come to find that the Egyptians used incredibly clever engineering techniques to accomplish their constructions with relatively small workforces.

All the stories about the eccentric using strange powers have been debunked. Though he was highly secretive, a few people did witness his construction techniques, which were as mundane—though clever—as they come. Still, though, it's pretty cool stuff.

_________

Quotable

Yes Yard Ramp Guy: Onward and backward with our quote-off. Xcellent, I say.

“X marks the spot.”

— Lots of people, including pirates, Indiana Jones, and me.

Here’s the Dirt

Or: Don’t Let Civilization Become a Stick in the Mud

Yep. That works.

Quick quiz: What's the most important resource for civilization? Let’s exclude water, which is, far and away, the most important (and would, ahem, leave me without the topic I chose to write about this week).

You’ll be tempted to say oil, but that's not even close. Nor is metal.

The correct answer? Dirt.

“Yes,” you’ll say, “dirt is literally everywhere. It's what the ground is made of, for Pete's sake. How can something so common be that important? I mean, yeah, we need it to grow all of our food, but it's not like we're going to run out anytime soon.”

Unfortunately, I've got some bad news for you but, naturally we'll first need to go back in time.

During the Roman Republic, the fields of Italy were famed for their fertility and were a big part of Rome's early conquests. And during the Roman Empire? All of the grain was shipped from the fertile fields along the Nile via the Port of Alexandria. In time, the fields of Italy were no longer capable of supporting the population of Rome; the soils had been exhausted of nutrients, with much of the topsoil stripped away.

Let's travel even further back to ancient Mesopotamia. The end of Mesopotamia's reign as the center of civilization ended due to the very thing that made it possible: irrigation. Long-term irrigation caused the salinity of the fields to increase until the fields were too salty for crops.

“But,” you’ll say, “we're talking thousands of years, here. Technology's increased to the point where we don't need to worry about that anymore.”

Nope. Doesn't work.

Sorry to be a downer, but we need to worry about it now more than ever.

Soil is fragile stuff that can take decades—sometimes centuries—to form. Our ancestors needed millennia to master agricultural methods that preserved the soil, and we've largely discarded their methods.

Terracing, contour plowing, no-till farming, use of compost and manure: those are no longer in the playbook for most of our farms, especially the largest ones.

Tractors, nitrogen fertilizers, and genetically engineered crops allow us to do an end-run on soil. We can use them to grow crops in even the worst soil, at least for three to four years.

After that? They just move to a new field. That's not sustainable, though. We're already using about 40% of the Earth's surface for agriculture. We can't keep moving fields forever. We're simply eroding away soil faster than it's produced.

This isn't a situation where there's going to be a simple technological solution, in large part due to the fact that this is a technological problem. Instead, we need to concentrate on careful husbandry of the land, especially encouraging small farms that use sound long-term strategies.

Thankfully, this is starting to happen, but it's got a long, long way to go. Every single civilization that's neglected its dirt has suffered for it. We've neglected ours for far too long.

_________

Quotable

Dear Yard Ramp Guy: Onward, reverse-alphabetically. In the meantime, you B most excellent.

“Years later, people look back upon their darkest day and say—as Churchill said of London's war years—‘This was our finest hour.' In a tough spot right now? You may be on the very edge of winning.”