Go Jump in a Lake

Or: Good Luck Getting There

The most interesting lake in the world is completely inaccessible.

Well, maybe not completely, but close enough for government work. Which, come to think of it, usually isn't that close.

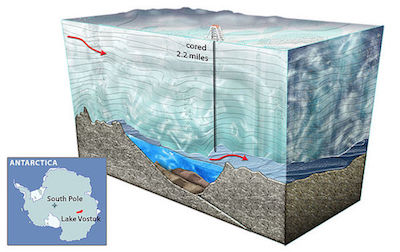

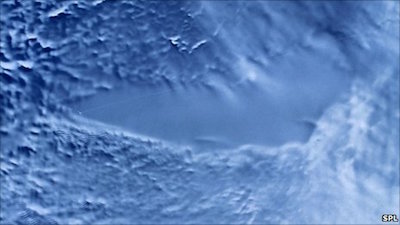

Lake Vostok is located in Antarctica. Bit of a strange place for a lake, I know, but this gets even weirder. Its surface is 500 feet below sea level. Lake Vostok is believed to have species of bacteria that are present nowhere else on the planet. It's also the largest lake in Antarctica, at more than 160 miles long and 30 miles wide.

And just to make all this interesting, there's a magnetic anomaly in one end of the lake.

And just to make all this interesting, there's a magnetic anomaly in one end of the lake.

Vostok Station, the nearby research facility, recorded the coldest known temperature ever on our planet. The lake has a single island, which no one has ever set foot on. It's also in complete darkness, even during the part of the year when Antarctica gets sunlight. That, of course, is because it's buried under 13,000 feet of ice.

As in: Lake Vostok is buried under a two and a half mile-high glacier.

Clearly impossible, right? Normally, yes, but in this case, the massive weight and compression created by the glacier caused its lowest layer to heat up, melting the ice and forming Lake Vostok. There are more than 500 of these subglacial lakes in Antarctic.

The hunt for life in Lake Vostok has become a major point of interest. Any creepy-crawly thing there would likely have been sealed off for the lake’s entire 15 million-year lifespan. The warm, oxygen rich, and pitch black waters would have created an ecosystem unlike anything else on the planet.

Unfortunately, there are concerns that the antifreeze used to maintain the boreholes through the glacier might contaminate the lake, so scientists are proceeding with extreme caution. While the overwhelming majority of species they have found could quite likely just be contaminants from the surface, they have found at least one previously unknown species that might very well have come from the lake itself.

Unfortunately, there are concerns that the antifreeze used to maintain the boreholes through the glacier might contaminate the lake, so scientists are proceeding with extreme caution. While the overwhelming majority of species they have found could quite likely just be contaminants from the surface, they have found at least one previously unknown species that might very well have come from the lake itself.

Mission to Mars? Sure. But Vacation in Vostok: now we’re talking…even though Maggie won’t hear of it.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Strange Case of a Non-Invisible Man

There's a poker saying I've always been fond of: “If you sit in on a poker game and don't see a sucker, get up. You're the sucker.”

It's a great rule to live by, and not just in poker, but it’s pretty distressing how many people have obviously never heard it. We've all met them: people who completely fail to recognize their own incompetence, or think that they are geniuses despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

There's actually a name for this: The Dunning-Kruger effect. Though it was hardly a stunning revelation to anyone, David Dunning and Justin Kruger were the first ones to actually test for the phenomena. They were inspired by a news story about a man named McArthur Wheeler, who robbed a pair of banks after smearing lemon juice on his face. Apparently, he thought that lemon juice would make his face invisible to cameras, since lemon juice is usable as invisible ink.

There's actually a name for this: The Dunning-Kruger effect. Though it was hardly a stunning revelation to anyone, David Dunning and Justin Kruger were the first ones to actually test for the phenomena. They were inspired by a news story about a man named McArthur Wheeler, who robbed a pair of banks after smearing lemon juice on his face. Apparently, he thought that lemon juice would make his face invisible to cameras, since lemon juice is usable as invisible ink.

During their testing, Dunning and Kruger confirmed that unskilled people frequently overestimated their competence. One of the experiments performed involved giving various tests to subjects and then showing the subjects their scores. They then asked the subjects to estimate their rank. Those subjects who tested poorly consistently ranked themselves as much as 50 percentiles higher than their actual score.

Dunning and Kruger found an interesting flip side to the effect: highly skilled individuals tend to frequently underestimate their own competence—or, rather, they overestimated the competence of others—an effect that seems quite similar to Impostor Syndrome, which occurs when people are unable to really acknowledge their achievements.

I usually don't have a lot of interest in psychology; I tend to read much more about other social sciences, especially history and archeology. Why am I getting into it now?

Easy. I'm willing to put a lot of work into my insults, especially when they involve incompetent coworkers.

The Kessler Cascade

Or: In Space, No One Can Hear You Take out the Trash

My family goes to a lot of movies. We're not film buffs, by any means. Usually, we're looking for snappy dialogue and explosions. A couple years ago, we saw the film “Gravity.” For those who haven't seen it, a runaway debris cloud destroys satellites and space stations. Even though the science in that movie was pretty badly off, in a lot of ways, something like it does have the potential to occur.

My family goes to a lot of movies. We're not film buffs, by any means. Usually, we're looking for snappy dialogue and explosions. A couple years ago, we saw the film “Gravity.” For those who haven't seen it, a runaway debris cloud destroys satellites and space stations. Even though the science in that movie was pretty badly off, in a lot of ways, something like it does have the potential to occur.

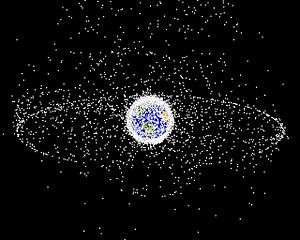

Kessler Syndrome is a hypothetical scenario dreamed up by a NASA scientist named Donald Kessler in the 70s. Essentially, it proposes that if enough objects are in low Earth orbit, collisions between them will eventually result in an enormous cascade of debris.

It's a pretty simple process: one piece of space junk slams into another, which sends debris scattering about. Some of that debris hits another piece of space junk, creating another burst of debris, which slams into more space junk, and then maybe into a satellite. Eventually, you have an enormous cloud of debris traveling through orbit. Each piece would be widely spaced, but even tiny bits can have insanely destructive power when moving that quickly. The cloud wouldn't take out every satellite, of course; it would stay in the same orbit, and many satellites would be in a higher or lower orbit.

A Kessler cascade could potentially make space travel impossible for millennia, completely blocking off that orbit. The debris wouldn't orbit forever. The drag from the miniscule amount of air at that altitude, along with a few other factors, would eventually clear the orbit again, though the process could take thousands of years.

A Kessler cascade could potentially make space travel impossible for millennia, completely blocking off that orbit. The debris wouldn't orbit forever. The drag from the miniscule amount of air at that altitude, along with a few other factors, would eventually clear the orbit again, though the process could take thousands of years.

Governments take the threat quite seriously. Satellites aren't allowed to launch unless they can be safely disposed at the end of their lifespans. The two most common techniques for doing so: dropping it back into the atmosphere or raising it up into a higher graveyard orbit. People also have proposed gadgets for clearing the debris, including a device called a laser broom, which is precisely as cool as it sounds.

It all really just goes to show: proper waste disposal is important, no matter where you are.

Mooning

Dust Busting in Space

For all of the billions of dollars spent getting to the moon, and with all of the challenges NASA had to overcome getting there, one of the most aggravating problems didn't crop up until astronauts had already landed: moon dust.

For all of the billions of dollars spent getting to the moon, and with all of the challenges NASA had to overcome getting there, one of the most aggravating problems didn't crop up until astronauts had already landed: moon dust.

Moon dust has a perfect storm of properties that’s an absolute nightmare to deal with. It's extremely fine grained, yet simultaneously abrasive, like someone ground up bits of sandpaper. The best way to think of moon dust is like powdered glass. It also has severe static cling, thanks to the solar wind continuously bombarding it, so it sticks to every bit of equipment—suits, lenses, you name it. Moon dust also gums up spacesuit joints, wears through layers, and gets all over habitats.

Part of the reason the stuff is so difficult to deal with is that it’s formed by meteor and micrometeoroid bombardments, unlike earth dust. Since there is no wind or water to erode the dust, it stays just as sharp as the day it was shattered off.

Moon dust even causes its own health condition, known as lunar hay fever, causing severe congestion and other problems. Long-term exposure to the dust could likely cause health problems very similar to silicosis.

That's not to say NASA hasn't been researching solutions for dealing with all that moon dust. Each grain contains a small fragment of metallic iron, which means that we can collect it with a magnet. The grains also melt quickly and easily with a microwave. One scientist even envisions placing microwaves on the front of lunar rovers, so that our astronauts could create “roads” as they travel.

The Moon hardly has a monopoly on dusty conditions. The dust on Mars is believed to be such a strong oxidizer that it can burn your skin, much like lye or bleach. Martian dust on your skin would leave burn marks.