Orchid Hunting

Or: How I Chose Something Else

I like to keep a lot of houseplants around—it really helps make a house feel like a home.

I like to keep a lot of houseplants around—it really helps make a house feel like a home.

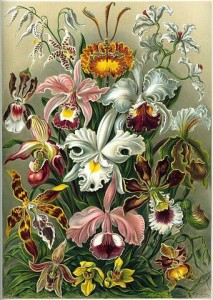

Maggie used to give me a lot of guff about my taste in houseplants. She said that I could easily get a job as a hotel decorator because I had the same taste in plants. So, just to please her, I decided to pick up a couple flowers…orchids, in this case.

I'd avoided orchids for years, since I'd heard many stories about how difficult they are to keep. So, before I bought some orchid plants, I decided to do my research. And that’s when I stumbled across something incredibly weird.

There is an enormous black market for orchids. Seriously! Orchids are a multibillion-dollar market with a large percentage of that value being illegal.

Orchids have been wildly popular since the 1700s, largely due to their extreme variety. There are literally thousands and thousands of species, with new ones being discovered all the time. Some species go for incredible prices—one rare orchid species, The Gold of Kinabalu, sells for over five grand per stem on the black market. This one commands its high prices due to its unique appearance, its protection by the government of Malaysia, and the fact that the plants take 15 years to bloom.

Eventually, the extreme demand resulted in rare and delicate orchid species being driven extinct in the wild, all over the world.

Eventually, the extreme demand resulted in rare and delicate orchid species being driven extinct in the wild, all over the world.

Governments quickly began passing laws to prevent their smuggling from countries or harvesting by unauthorized personnel. But: since most of the countries involved merely punish offenders with fines—or short jail terms—at most, the legal threat isn’t a huge deterrent; potential profits are simply too large.

Some orchid species are being wiped out by orchid hunters before they even have a chance to be described by science.

I ended up going with a couple Cyclamen plants instead.

On Living Bridges

I've blogged a lot about bridges, I know (Sir Bridges Blog-a-Lot, eh?) but I haven't yet explored living bridges.

Meghalaya, a state in north-eastern India, is one of the wettest places in the world, getting close to 500 inches of rainfall a year. Almost three-quarters of the state is forested. One of the indigenous tribes living there, the War-Khasi, build living foot bridges from the roots of the Ficus elastica — a variety of rubber tree.

Photo by Arshiya Urveeja Bose [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Arshiya Urveeja Bose [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

To grow the bridges, the Khasis create root guidance systems out of halved and hollowed betel nut trunks. The roots are channeled to the other side of the river, where they are allowed to bury themselves in the soil on that side.

The bridges take 10 to 15 years to grow strong enough for regular use; once they do, they last incredible amounts of time with no maintenance: since they're still growing, they actually continue to grow stronger and stronger over time. Some of the older bridges are five centuries old. Many of the older, stronger bridges can support 50 or more people at once.

The most famous of the bridges, the Umshiang Double-Decker Root Bridge, is actually two of those bridges, with one stacked directly over the other. Local dedication to the art has kept the bridges alive and prevented them from being replaced with steel. (Steel, frankly—and with all respect to those dealing with, ahem, yard ramps—don't have anything near the lifespan of the root bridges and aren't nearly as sturdy.)

The most famous of the bridges, the Umshiang Double-Decker Root Bridge, is actually two of those bridges, with one stacked directly over the other. Local dedication to the art has kept the bridges alive and prevented them from being replaced with steel. (Steel, frankly—and with all respect to those dealing with, ahem, yard ramps—don't have anything near the lifespan of the root bridges and aren't nearly as sturdy.)

The root bridges aren't the only living bridges around. In the Iya Valley in Japan, there are bridges woven out of living wisteria vines. They're much less common, and only three remain. They're built by growing immense lengths of wisteria on each side of the river before weaving them together—a process that must be repeated once every three years.

These wisteria bridges are much less sturdy than the Khasi root bridges, with wooden planks spaced over seven inches apart, and they apparently shake wildly while you're on them. By all accounts, these things are terrifying to cross, which makes sense: they’re widely thought to have been designed originally for defense. The original bridges didn't even have railings.

Hutton’s Geology

Everyone knows about Charles Darwin and Galileo Galilei. They're the closest thing to science rock stars. One battled the Catholic Church at the height of its power and performed experiments involving dropping objects off buildings. The other took a voyage around the world and developed a whole new science. They have fascinating, memorable, and dramatic life stories. They’ve earned rock star status.

Geology has its own Darwin, but he's hardly as well known.

James Hutton was far from an adventurous man. In fact, most of his discoveries came about from exploring the same small area close to where he lived.

Hutton was a Scottish gentleman farmer, commonly known as the Father of Modern Geology. By observing layers of dirt and stone, he was the first to consider that these layers might indicate great age.

In his day (the mid and late 1700s), most other geologists looked to various theories involving floods to explain the layers. Hutton, though, theorized that the Earth was incredibly hot inside, and that sediment swept into the ocean melted and was pushed upwards. Which wasn't too far from today’s consensus, at least compared to most of his contemporaries.

Part of the reason that Hutton isn't well remembered today is that he was a much worse writer than other prominent geologists of the time. Hutton's book Theory of the Earth; or an Investigation of the Laws observable in the Composition, Dissolution, and Restoration of Land upon the Globe was much less readable for the general public. Plus, the title is just less catchy than, say, On the Origin of Species. Much, much less catchy.

Another reason? Rocks just aren't that interesting to most people.

I’m The Yard Ramp Guy®

Well, I’m just pleased as punch to be officially presented as The Yard Ramp Guy. It’s not complicated, but those of you who know of and have been reading me understand that I’m gonna try explaining anyway.

Well, I’m just pleased as punch to be officially presented as The Yard Ramp Guy. It’s not complicated, but those of you who know of and have been reading me understand that I’m gonna try explaining anyway.

Guy named Jeff Mann called me about a year ago. Said he’d started reading my blog and my Facebook page and my Twitter tweetings. Said he’s the original Yard Ramp Guy but enjoyed my musings and wanted to know if I’d be interested in becoming an official Yard Ramp Guy licensee.

And, yes, I must admit that it cracked me up. Now, I was there when Unser won at Indy (I’m not gonna say which Unser and which year, in order to keep you from thinking me full of formaldehyde). Just being there was like I won the darn race myself, even though I personally drive so below posted speed limits that my Chevy has probably attained consciousness in order to become offended by me.

So, when Jeff contacted me and floated the idea of my becoming a Yard Ramp Guy, it felt like the second thing I’ve ever won.

I said yes…with the following conditions:

1. I can write about whatever I want—yes, the ramp rules but I need to explore everything (just ask Maggie and the kids).

2. No editing or censoring (just ask Maggie and the kids).

Jeff was game with the additional requirement that I put my face on his logo so I am using the licensed trademark correctly. I LOVE that part—which is about the only instance of vanity I’ve ever had (just ask Maggie and the kids).

Jeff was game with the additional requirement that I put my face on his logo so I am using the licensed trademark correctly. I LOVE that part—which is about the only instance of vanity I’ve ever had (just ask Maggie and the kids).

Jeff and I have been friends ever since.

Why Mr. Mann likes me, I don’t know. I’m just a guy with a fascination for things that work (and a soft spot for things that don’t work). I like inventions and ideas that help advance civilization and culture. And I like to write about them.

Really, though: the ramp is central. It’s not for nothing that this site is called The Ramp Rules. I love the invention of it, the idea behind it, the things that have been constructed with its sheer and fairly simple brilliance. (Click HERE for my Top Five favorite inventions.)

Beyond that, I like the way Jeff and his team conduct business. I like what they call the weaving together of “old-school values with 21st-century technology.” I think The Yard Ramp Guy is proof positive that it’s still possible to conduct yourself as a gentleman and be successful in business.

World needs more of that.