Archive: McCoy vs. The Volcano

How a Volcano Invented Science Fiction & the Bicycle

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: thar she blows...

It Begins...

On April 5th, 1815, Mount Tambora—in present-day Indonesia—began erupting.

The noise made by these eruptions was loud enough to be heard hundreds of miles away. Some English garrisons thought it was cannon fire and sent troops around their islands to investigate.

The eruptions continued until the whole mountain exploded from April 10th and 11th. Mount Tambora's eruption was the single largest in recorded history. So much ash was blasted into the sky that it was pitch black outside as far as four hundred miles away from the mountain.

Tsunamis ravaged the shores of countless islands, and countless more died from ashfall-related complications. (Volcanic ash is really, really nasty stuff, filled with tiny bits of volcanic glass that shred your lungs. Note to file: Don't breathe it in, and don't drink water contaminated with it.)

That was just the start of things, though. By 1816, the Mount Tambora’s airborne ash had spread through the atmosphere to the Northern Hemisphere, kicking off the Year Without a Summer.

A dry fog persisted throughout the spring and summer (what scientists call a “stratospheric sulfate aerosol veil”) that blocked much of the sunlight and kept the temperature from rising to normal levels. Frost began killing off crops in North America, and heavy rain drowned crops in Europe.

Massive famines cased severe social unrest and famine. Hundreds of thousands died in North America, Europe, and Asia. Hungary experienced brown snow, while Italy saw red snow falling throughout the year. The family of Joseph Smith was forced to leave Vermont due to famine, kicking off a chain of events that would lead to the founding of the Mormon Church.

Karl Dranis was inspired by the lack of horses in Germany (no oats to feed them) to invent the velocipede, ancestor of the bicycle.

Mary Shelley, trapped in a Villa with her husband and friends, decided to have a contest to write the scariest story. Her entry, Frankenstein, is commonly considered the original science fiction novel.

I could go on listing consequences for a while. The rapid migration into Indiana and Illinois, leading to their statehoods. Spectacular sunsets. And on and on.

Mount Tambora’s eruption changed the face of the world as we know it. Here's the thing, though: This isn't an anomalous event. It is a singular one, due to its size, but natural disasters and climatic events are major drivers of history, and are far-too seldom treated as such. The current civil war in Syria? One of the primary causes is a drought that led to crop failures.

As much as we like to pretend that we're the bosses of the planet, we need to remember how big our planet is, and how easily it can devastate civilization with a slight shrug.

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Forklift Ramp Customer Service

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy shows us how repetition makes reputation.

Click HERE to read how he continues to create satisfied customers.

Archive: The World is Still Round

But Kansas is Still Flatter Than a Pancake

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: a flat Earth is more like a flat tire...

Quick quiz: When did humanity discover that the Earth is round?

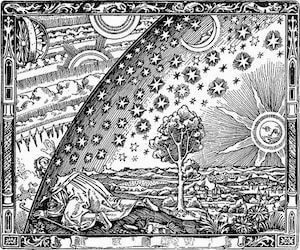

Note the Roundness.

If you answered Copernicus or Galileo, you're off by a millennia or two. The Ancient Greeks actually discovered this.

To prove the theory, they created an experiment using two dry wells, hundreds of miles apart. Then, at noon on the same day, the Greeks measured the shadows at the bottom of the well to see if they were at the same angle. When they weren't, they used the difference in angle to figure out the actual size of the Earth…with remarkable accuracy.

(Trigonometry is important, kids. If you don't believe me, just ask Jeff over at The Yard Ramp Guy.)

Okay, another quick quiz: When did humanity forget that the world was round?

I bet the most specific thing you can think of is the Dark Ages or the Fall of Rome, right? Well, both are incorrect: We never forgot.

Careful, buddy.

To quote the brilliant Stephen Jay Gould, "There never was a period of 'flat Earth darkness' among scholars (regardless of how the public at large may have conceptualized our planet both then and now). Greek knowledge of sphericity never faded, and all major medieval scholars accepted the Earth's roundness as an established fact of cosmology."

In fact, we can trace the popularization of the idea that people thought the Earth was flat back to specific historians in the 1800s.

Sadly, this is pretty common stuff when we think about history.

People are swift to assume that their distant ancestors (or at least other people's distant ancestors) were dumber than people today.

It really doesn't take that much effort to realize that idea is wrong, but most people won't even try to put in the effort.

(Really don't believe me? Then let's see you design an aqueduct with pen and paper.)

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Yard Ramps for Forklifts

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy honors both John Henry and forklifts. In my eyes, you can't do much better than that.

Click HERE to witness progress at its finest.

Archives: Gorge-ous

Or: Hooked on Fishing

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series:something fishy is definitely going on.

The one that didn't get away.

Fishing: It predates civilization…even the human race. (Birds fish, after all.)

There are plenty of ways people fish, ranging from fishing spears (which are really, really difficult to use) to nets. The best way, or at least most fun, is with a hook and a line. And it's a very old way.

The oldest fish hook in existence was carved out of shell. Fishing hook hunters (or stumble-uponers) found it in East Timor, and it dates back to as much as twenty-three THOUSAND years.

Shell was an extremely common material for ancient fish hooks. Our ancestors crafted hooks from bone, wood, horns, stone, bronze, and eventually iron. Each one of them, however, had problems of its own. Wood, for instance, floats, and that necessitates weights, or heavier bait. One common workaround was using multiple of these materials to leverage their strengths.

Fishing hooks became more common in the archaeological record around 7000 BC. Many of the early fishhooks lacked barbs, which would have made it much more difficult to fish with. In fact, one of the earliest types of fishing hook, known as a gorge hook, wasn't even curved.

The gorge hook is a small stick tapered to a point on each end. A small groove is cut around the middle, where a cord is tied. The cord is then wrapped along the length of the gorge hook, securing a piece of bait to it. When the fish grabs the bait, the cord comes unwound, which then results in the gorge hook turning sideways and lodging in the fish's throat.

This does require you to know the average length of fish in the area, though. The gorge hook has the distinction of being one of the few hooks that aren't prone to stabbing into your thumb.

Fishing with an antique-style hook is definitely a challenge. But the satisfaction you get makes it worthwhile.

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: Pricing Transparency

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy admirably shows how transparency and honesty go hand in hand.

Click HERE to discover the best surprise.

Archive: Surviving Absurdity

Or: How to Make a $1,500 Sandwich

My good friend Jeff Mann, the true Yard Ramp Guy, has asked me to revisit some of my original posts. This week in my From the Archives series: everyone has, um, a (sandwich) price.

Me...thinking 'bout making a rich sandwich

Have you ever made food from scratch? If you said yes, you're probably thinking of cooking bread from flour and yeast and so on.

You probably aren't thinking of growing the wheat, harvesting it, milling it, and all that jazz. One guy in Minnesota, however, decided to actually cook a chicken sandwich from scratch. It took him six months and cost him $1,500.

Little bit ridiculous, right? We’ve evolved our modern society toward specialization in order to reduce the workload on people and prevent us from having to do such outrageous things.

The most interesting aspect of this is, of course, the salt: the guy from Minnesota had to fly to the West Coast to harvest his salt. If he wanted to be a purist, he would have needed to either walk all the way to the ocean or build his own airplane from scratch.

Obviously, that’s too much work for a YouTube video.

If he wanted to be even more of a purist, he would have needed to build all his tools himself. No stove; rather, an open fire. And no metal pot; he would have needed to fashion his own cookware instead. You can see how quick the absurdity things would’ve gotten.

So where am I going with all this?

I made me a sandwich…for $3.45

Believe it or not, I wanted to talk about survivalists. The typical survivalist strategy is to master a certain number of survival skills and to accumulate massive amounts of resources for survival purposes.

The missing ingredients? Almost everything, really. Our society has accumulated unbelievably huge quantities of knowledge dedicated toward merely keeping civilization running, mostly in the form of working professionals.

If someone were to make all of society's doctors disappear, we wouldn't be able to just set a bunch of people to the books and expect them to become doctors in a decade or so. Civilization reconstruction is a problem of a magnitude more significant than assembling a sandwich from scratch.

Any society emerging from survivalists in the wake of the collapse of civilization is going to be fairly primitive, by necessity.

And just to reassure Maggie and the kids and my gaggle of grandkids: I'm not investing in survivalist gear. Modern civilization is pretty durable. Gambling on it failing seems like way too much of a sucker bet to me.

Yard Ramp Guy Blog: The Diesel Blues

This week, my friend The Yard Ramp Guy turns the simple (chart) into the profound. Oh, and there's George Foreman, too.

Click HERE to fuel your day.