Tokyo Gets Drained

Flooding (you with) Information

There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel—is a flood water diversion facility.

There's an enormous underground chamber just north of Tokyo. The Underground Temple—also known as the G-Cans Project, or the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel—is a flood water diversion facility.

“Enormous” might be an understatement. It’s more than 25 meters high and 177 meters long. The concrete room is held up by 59 immense, 500-ton concrete pillars. In addition to the main chamber, there are five huge underground silos, each 65 meters deep and 32 m in diameter. You could quite literally fit Godzilla in one of those.

Construction on it began in 1992 and didn't complete until 2009. The whole thing is essentially the world's largest drain. The silos and the Temple are linked by hundreds of miles of underground pipes. The entire complex is nearly four miles across.

Tokyo has suffered from frequent floods throughout its history—not just from heavy rain, but also from typhoons and tornadoes. G-Cans was built to withstand even the most massive, once-every-other-century floods. Its 14,000 hp turbines and 78 pumps are capable of pumping more than 200 tons of water per second into the nearby Edogawa River.

The architects and construction crew faced a number of major difficulties in the construction. Earthquake proofing was one of the biggest hurdles. Another: preventing buckling and sagging in the ground overhead as they dug out the complex; it is directly underneath a city, after all.

The architects and construction crew faced a number of major difficulties in the construction. Earthquake proofing was one of the biggest hurdles. Another: preventing buckling and sagging in the ground overhead as they dug out the complex; it is directly underneath a city, after all.

There was a little criticism about the steep price tag ($2 billion) and the fact that Tokyo already possessed significant flooding defenses. Still, given how prone to natural disasters the city is, I certainly think they made the right call.

So, they have the flood prevention thing covered. Of course, there are still earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, typhoons, Godzilla, and those horrifying giant Japanese hornets to worry about.

Things, Explained

A Roboticist-Cartoonist Version of Things

Even though I read a lot, I usually don't recommend books to others. My favorites usually aren't too interesting to most people—lots of books on obscure parts of history, old pulp westerns, and dry technical volumes.

While Christmas shopping, though, I found a book that I loved so much that I bought copies, not only for my grandkids but myself, too.

His ducks in a (vertical) row.

It's called Thing Explainer, written by a former NASA roboticist turned cartoonist named Randall Munroe. The premise is pretty straightforward: the book is filled with diagrams of various gadgets, natural phenomena, and scientific concepts, but all the actual explaining is done using only the thousand most commonly-used words in the English language.

In practice, it can get a little silly. Bridges are called “tall roads,” planes are called “sky boats,” and the Saturn Five Rocket is called “Up Goer Five.” All of which earned more than a few chuckles from me.

Added bonus: The actual diagrams and explanations are absolutely top notch. I like to think I'm decently well educated when it comes to science, and yet I still learned quite a bit from Thing Explainer, often in the form of completely new tidbits of knowledge, sure, but just as often knowledge presented in a way that is novel and better for comprehension.

Thing Explainer isn't the kind of book you read in one or two sittings. It's more of a coffee table book you thumb through here and there. Of course, I read it all in one sitting, but I'm just not very good at delayed gratification when it comes to books. (Or when it comes to dinner. Or dessert. Or vacations.)

__________

Paying it Forward

Like book recommendations, I’m not too big on endorsements (unless it’s for ancient inventions that are perfectly great to help the 21st century keep on keeping on).

And then along comes that other Yard Ramp Guy, Jeff Mann, who just the other day introduced me to the Grasshopper Entrepreneur Scholarship. Since I don’t believe my School of Life credentials currently qualify me as an eligible entrant, I offer it up to all you legal young’uns—either in college or headed there.

Here’s the rub—and why I’m happy to present it to you: This year’s essay topic is, “What does market disruption mean to you as an entrepreneur? What would you do to create market disruption for your business?”

Me, I’m all about market disruption. (In my family, Maggie defines this as whatever I’ll do to get out of going to the grocery store.)

A $5,000 scholarship awaits the winner. Go get ‘em.

Earth Art

You’re Gonna Need a Bigger Boat

I am not a well educated man when it comes to art. Give me a ten-dollar painting of a sailing ship from a yard sale or thrift store and I'll be perfectly happy with it. Every once in a while, though, I find something that makes me take notice—in this case, it's a fella named Michael Heizer.

Heizer is known as what we call a land or earth artist—someone who builds immense outdoor pieces designed around and for their specific locations. These pieces are left out in the open to age and erode naturally. (Kinda like me.) Many of the earliest pieces from the 1960s don't exist anymore. If nothing else, Heizer's pieces are particularly notable for their sheer size.

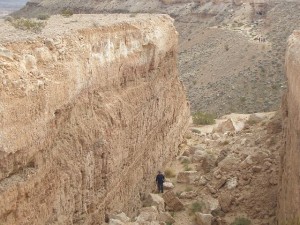

One of his best known pieces is a work called Double Negative, a pair of massive trenches cut into the edge of Mormon Mesa in Nevada. Each is 50 feet wide and 30 feet deep, and they have a combined length of 1,500 feet. The project involved moving 244,000 tons of rock.

One of his best known pieces is a work called Double Negative, a pair of massive trenches cut into the edge of Mormon Mesa in Nevada. Each is 50 feet wide and 30 feet deep, and they have a combined length of 1,500 feet. The project involved moving 244,000 tons of rock.

Another project, Levitated Mass, involved the suspension of a massive, 21-foot tall, 340-ton boulder above a concrete trench that you can walk through. Moving the boulder itself was a massive feat of engineering. It only had 60 miles to travel, as the bird flies, but in order to get there they took it on a tangled 106-mile route through 22 cities in order to find bridges strong enough and streets wide enough.

The colossal custom transport could only move at seven miles an hour, and so they needed 11 days to get there, traveling only at night. Along the way, they had to cut down trees, temporarily remove traffic lights, and tow cars. The whole route turned into a series of parties at the transport's daytime resting places.

(The event was so cool that our other Yard Ramp Guy has blogged about it.)

Heizer’s current project, in the works for 20 years now, is by far his most impressive. Not yet open to the public, it is an enormous, mile-long monolithic structure known only as City, with two smaller complexes nearby.

To give you a comparison, it's about the size of the National Mall in DC. It's located in the brand new Basin and Range National Monument. As soon as it opens to the public, you can bet I'll be visiting.

_________

Clf23 at English Wikipedia [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Now Dig This

One Way to Save on Airfare to China

Little kids try to dig to China all the time—regardless what’s actually on the other side of the world from them—and, well, they never get very far—because…

It’s dinnertime, or they bust a pipe and flood the basement, or mom comes out and tells them they can’t go because your passport is outdated and you’ll get tossed in jail and just wait till your father gets home, and when dad gets home he stares at them with a look that’ll keep‘em local for at least 12 more years.

And now that I’ve covered parenting tips and travails for the moment, what's the actual deepest hole ever dug?

The Kola Superdeep Borehole, on the Kola Peninsula in northern Russia, reaches a depth of 40,230 feet. That’s more than seven and a half miles, far deeper than even the deepest point in any ocean. Started by the Soviet Union in 1970, it held the record for deepest borehole for decades.

The Kola Superdeep Borehole, on the Kola Peninsula in northern Russia, reaches a depth of 40,230 feet. That’s more than seven and a half miles, far deeper than even the deepest point in any ocean. Started by the Soviet Union in 1970, it held the record for deepest borehole for decades.

Though longer boreholes have since been drilled, largely for oil related purposes, the Kola Superdeep Borehole remains the deepest point on Earth. During its lifespan it contributed immensely to scientific understanding.

Work on the borehole shut down in 2005, due to lack of funding. Oh, and though the hole is still there, you can't fall into it: along with being sealed with a thick metal cap, it's too thin to accommodate a human.

Even though that project has ended, it's not the only one of its type.

The Chikyū, a Japanese scientific vessel, is a drilling ship designed to drill miles below the seafloor. While that won't likely ever reach the extreme depths of the Kola Superdeep Borehole, its data is much more scientifically interesting, through drilling into more seismically active regions where the crust is much thinner. The Chikyū might actually be able to reach the upper layers of the mantle.

(Fun fact: the boundary between the crust and the mantle is known as the Mohorovičić Discontinuity, though most geologists just call it the Moho.)

Why is it important to dig all of these holes? Well, apart from giving us a richer understanding of the Earth’s history, (which should be important enough on its own), we also gain more knowledge of continental drift, volcanism, rock formations, and mineral deposit locations.

That’s why we can thank all those who started digging those holes to China as kids, got interrupted by their meddling parents, and then returned to the dig after college. The way I see it: if the parents had only let their kids have at it, they would’ve saved a fortune on tuition.