Patching the Patch

The Deep Blue Sea

Last time around, I took on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. It's a floating collection of garbage, about the size of the state of Texas and largely composed of floating bits of plastic. The patch is an alarming thing, and I’ve placed it solidly in my “Cautionary Tales” category, which now has 35 entries since I began blogging.

Lest you think I’m all about doom-and-gloom scenarios, I also discover rays of hope in my reading and research. This is one of them:

A young inventor thinks that he's found a solution to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Boyan Slat, born in 1994, (yes, I did say he was young), spent much of his youth near and in the ocean. Time and again, he encountered plastic in the waters. Eventually, he grew really bothered by how pessimistic people were about developing solutions to ocean plastics. And so, in a fine example of youthful idealism balanced by realism, he decided to do something about it himself.

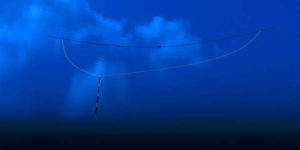

Boyan’s project, The Ocean Cleanup, is developing a large-scale, passive method of removing floating plastic. Essentially, his invention is a large, floating U-shaped pipe that will gather the plastic bits as it drifts.

To ensure that the device collects enough, it will employ a sea anchor—hanging down in the water, increasing drag via an extremely un-hydrodynamic shape— to slow down, so that the plastic flows faster through the gyre than the pipe. This is designed to ensure the plastic runs into—and not under—the capturing pipe.

Naturally, the project has its critics. Most of the plastic in the ocean is made up of particles too small for the system to gather. Quite a bit of plastic ends up on the seafloor, as well. Both of these criticisms, and quite a few of the others, tend to focus on the idea that this project doesn't do enough or is inefficient.

Those are legitimate criticisms, but they also ignore the fact that at least Boyan Slat and his project are doing something. Something is a lot better than nothing. And nothing is about exactly what we've been doing so far to solve this problem.

_________

Quotable

Yard Ramp Guy: Quotations are plentiful. Just look:

“Jazz is a spectacularly accurate model of democracy and a look into our redemptive future possibilities.”